Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Asides and references – visual or vocal – can frequently be aimed at the cognoscenti who get to smile with that smug, wry amusement of recognition.

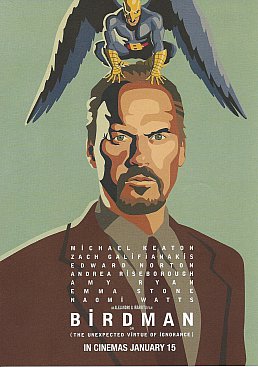

And there are certainly moments in the first third of the acclaimed Birdman (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) by director Alejandro G. Inarritu which are like that.

When our central character Riggan Thomson -- a former film star now trying to revive his career with a Broadway production he has underwritten -- is interviewed backstage before the production opens it is by a pompous, intellectual critic who is so overdrawn as to be a willful caricature, an equally cliched gossip columnist and a couple of middle-aged Japanese men who seem to understand no English but mistakenly pick up on what they think the actor/director has said.

It's a funny scene, but is an exaggeration of an in-joke.

The premise of the film is a good one however: Thomson (Michael Keaton, who once played Batman remember) had been a cinema star as the superhero Birdman but after three films in the franchise his career hit the skids. He's now in “the legitimate theatre” directing and acting in a version of What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, based on the stories of Raymond Carver.

It's an ambitious play . . . but he doesn't have another male lead (sudden injury takes out the hopeless original cast member) until the arrogant, method-actor Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) arrives and further disrupts proceedings.

The comedy gets darker, the desperation rises, Thomson encounters a poisonous and powerful New York Times critic (Lindsay Duncan) who is determined to keep Hollywood names out of the rarified world of proper theatre . . .

But beyond the narrative is another dimension.

In a nod to magic realism and superhero films, Thomson appears to have – or at least he believes he has – special powers like the ability to move objects and perhaps even fly.

To say more would give away too much, but as his claustrophobic world of the theatre closes in – it is astutely made so by the long narrow backstage corridors, the incessant drumming of a street musician outside – and Thomson's personal life (the ex-wife, junkie daughter, the inner monologue of Birdman) gets even more oppressive, your sympathies turn towards him.

Director Inarritu (21 Grams, Babel, Biutiful) walks a fine line between pathos, humour and the hyper-realism of Thomson's inner life and fantasies, but also nails some astute social comment about the cinema, the ego of actors and the power of social media. And the demands of the live stage, especially when so much personal and financial investment depends on the success of a production which seems doomed to fail.

Birdman is an emotionally dense film with wit and visual style (at one point is becomes a parody of a blockbuster), one which which requires the suspension of disbelief in its tumbling ride, does have in-jokes and is already picking up awards.

And Keaton is terrific.

Birdman opens in New Zealand cinemas on January 15

post a comment