Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Salvador Dali once said, “The only difference between a madman and myself is that I am not mad”.

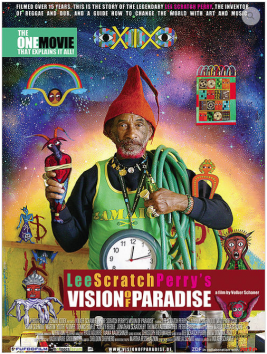

The revolutionary reggae producer and musical constructionist Lee Scratch Perry might well say the same. But Perry – whose brain is wired very differently from most people and who speaks in terms of visions, dreams, magic and Biblical revelations – would doubtless say it very differently, if perhaps utterly incomprehensibly.

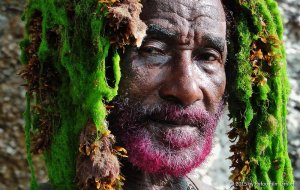

Perry, who has lived in Switzerland for decades now, finds mythic inspiration in stones, the battle against Satanic forces and a very personal religion. And his sentences which frequently rhyme even if they don't make much sense.

This fascinating 90 minute doco (on DVD, through Southbound) finds Perry at home enacting his own strange rituals before looping back to the Jamaica of his birth with commentary from the likes of Perry's biographer David Katz and placing Perry's faith into the context of Marcus Garvey and Rastafarianism.

Given Rastafarians' interpretation of the Bible (or the Holy Piby most often) is based on metaphor and symbolism it is hardly surprising that Perry has come to live in such a world.

The story becomes usefully chronological however as it picks up Perry's Black Ark studio in Jamaica where he recorded Bob Marley when the singer became a spiritual man.

The sound which Perry got out of Black Ark was unique and Perry's sonic vision created remans a defining force in reggae and dance music today.

Archival footage fills in the gaps as

Perry – among the ruins of the place he burned down – speaks

about working there in a place which became a shrine, and of the

prophecy and revolution that needed to be fulfilled to conquer evil

through music.

Archival footage fills in the gaps as

Perry – among the ruins of the place he burned down – speaks

about working there in a place which became a shrine, and of the

prophecy and revolution that needed to be fulfilled to conquer evil

through music.

Evil arrived however, in the form of Jamaica teetering into civil war and dangerous types turning up wanting to be turned into superstars like Marley. He adopted bizarre behaviour to scare people off then set the studio alight and eventually left the country.

By that time he was acclaimed globally, had released an astonishing body of work (which grows apace every year) and his live dub performances became legendary.

He became something different – more a poet and philosopher – after he left his homeland. Some of his most recent music has been more approachable although still determinedly singular.

Throughout are sonic samples from Perry's early reggae and innovative dub as he paints his boots, wears a wizard's hat and speaks in his mystical and magical way.

And numerous producers and artists – Youth, Mad Professor, Dennis Bovell, Ashley Beedle and others – attest to his genius . . . which quite obvious given the musical evidence.

He also makes penetratingly clear if sometimes reductive observations about politics and culture, but you can't deny he is also something of a mystic magician, and in possession of unique visions of art, symbolism and religion.

By the end of this most will find themselves more knowledgeable if no wiser.

And given its subject, that is exactly as it should be.

But, like Dali, he is not mad. Just crazily sane.

post a comment