Graham Reid | | 4 min read

When Jann Wenner launched Rolling Stone magazine in late 1967 his avowed intention was to take the emerging rock culture and its artists seriously as voice from and for the counterculture.

He was also candid enough to admit however that, as an uber fanboy, he also wanted to meet his his idols like John Lennon and Mick Jagger who by that time were well on the way to becoming something other than just rock stars.

They, and so many like them, were celebrities.

Wenner succeeded on both counts but in a way, within a decade, it was the latter ambition which was proving perilously close to becoming Rolling Stone's undoing.

The young, enthusiastic, gifted and street-connected New York writer Chuck Young whom Wenner hired in '75 – after Wenner asked him in the job interview what his favourite Stones and Dylan albums were – told author Robert Draper that “Jann completely identified with the celebrity aspect of rock'n'roll, the new royalty. It's like the difference between Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. Mick Jagger is a celebrity. Keith Richards is a rock'n'roller.

“And Jann I don't think was in any way conscious of the distinction.”

By way of example Young noted that

Wenner would demand coverage of Art Garfunkel's new album at a time

when bands like the Ramones and Talking Heads were emerging. But Art,

as with so many of Wenner's favourite artists, was a close friend and

dinner guest. That he was musically irrelevant didn't matter, or

Wenner didn't see it.

By way of example Young noted that

Wenner would demand coverage of Art Garfunkel's new album at a time

when bands like the Ramones and Talking Heads were emerging. But Art,

as with so many of Wenner's favourite artists, was a close friend and

dinner guest. That he was musically irrelevant didn't matter, or

Wenner didn't see it.

Often Rolling Stone missed key connections – its writers never rated Led Zeppelin for which the band members held a long-standing grudge, Wenner didn't get the Pretenders until he heard Pete Townshend approved of them, early Neil Young and Joni Mitchell were ignored . . .

Wenner was right about the Sex Pistols though, putting them on the cover would be the kiss of death at newsstands. And it was.

But none of that, nor its decline into its coverage of corporate rock and jogging from the great days of outrider writers like Hunter S Thompson, the young Cameron Crowe and the best work of photographer Annie Leibovitz (who as early as the late Seventies was taking two days to photograph a Coke can) can deny the fact that Rolling Stone changed the way we think about popular culture and music.

By taking rock (and blue and folk etc)

seriously in the late Sixties and beyond, it legitimised it and its

listeners in mainstream consciousness and the wider cultural

landscape.

By taking rock (and blue and folk etc)

seriously in the late Sixties and beyond, it legitimised it and its

listeners in mainstream consciousness and the wider cultural

landscape.

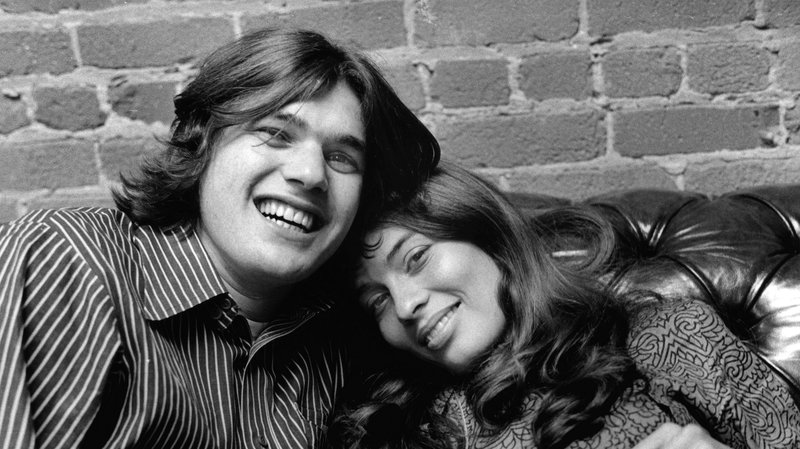

The ambitious young Wenner (who added the extra “n” to Jan to give it added cachet) admired more senior writers like Ralph J Gleason – an astute jazz critic with an ear to pop music – of the San Francisco Chronicle who was a father figure-cum-mentor. Wenner (and Gleason as Contributing Editor) saw that what was emerging in the Free Speech Movement out of Berkeley and other politicised places had a direct parallel within popular music. The protesters and liberal thinkers had Hendrix and the Beatles as its soundtrack.

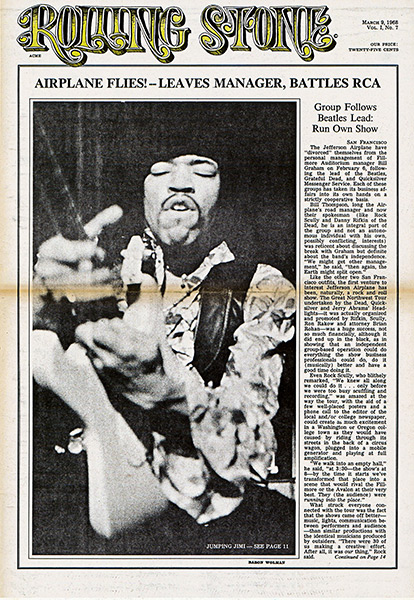

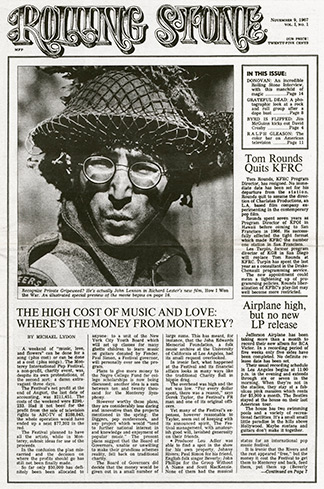

Borrowing $US7500 – which was a lot

of money then – Jann Wenner and his wife Jane found a cheap space

in San Francisco, a small cabal of writers including Gleason as

Consulting Editor and in October '67 with the publication of Stone's

first issue (Lennon on the cover, no interview though) began a

journey that had many highs (some commercial, others pharmaceutical)

and just as often veered towards the ditch of bankruptcy or worse,

irrelevance.

Borrowing $US7500 – which was a lot

of money then – Jann Wenner and his wife Jane found a cheap space

in San Francisco, a small cabal of writers including Gleason as

Consulting Editor and in October '67 with the publication of Stone's

first issue (Lennon on the cover, no interview though) began a

journey that had many highs (some commercial, others pharmaceutical)

and just as often veered towards the ditch of bankruptcy or worse,

irrelevance.

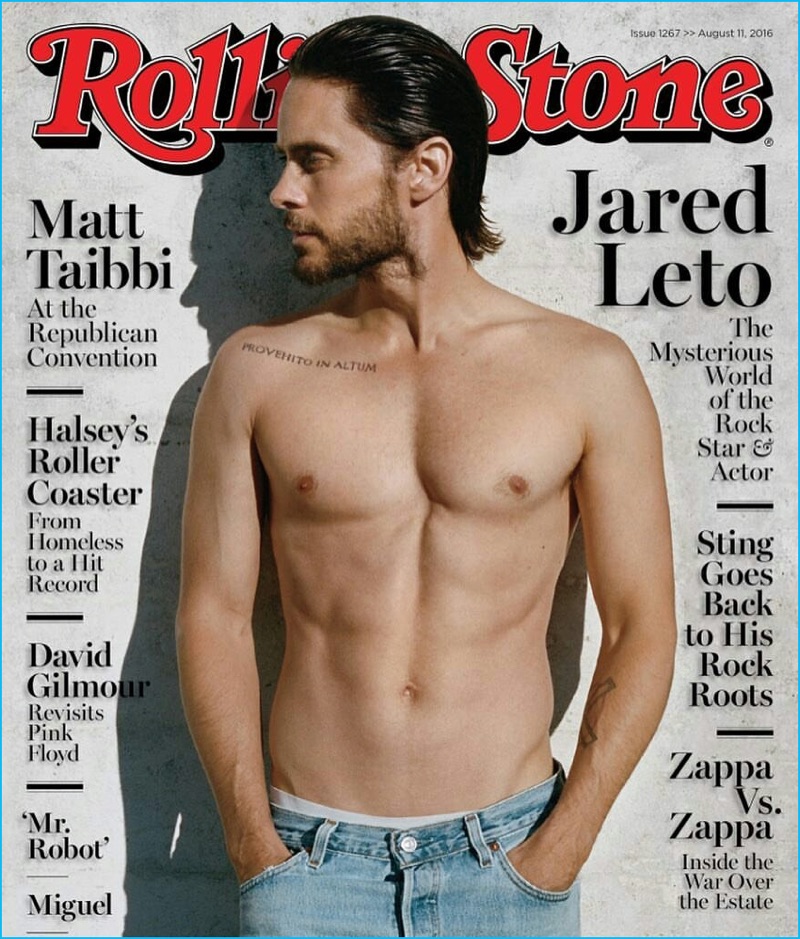

These days – and indeed for many decades now – Wenner has been a much reviled character, one whose motivations, money shenanigans and corporate ambition have seen him characterised as some kind of anti-Christ to the counterculture he championed.

But again, that takes nothing away from

the remarkable story of Rolling Stone as recounted in this six-part

doco series – numerous interviews with Stone writers, rock and soul

act in performance or conversation, readings from key articles which set the tone of the magazine – starting on Prime (Tuesdays from March 6,

9.35pm).

But again, that takes nothing away from

the remarkable story of Rolling Stone as recounted in this six-part

doco series – numerous interviews with Stone writers, rock and soul

act in performance or conversation, readings from key articles which set the tone of the magazine – starting on Prime (Tuesdays from March 6,

9.35pm).

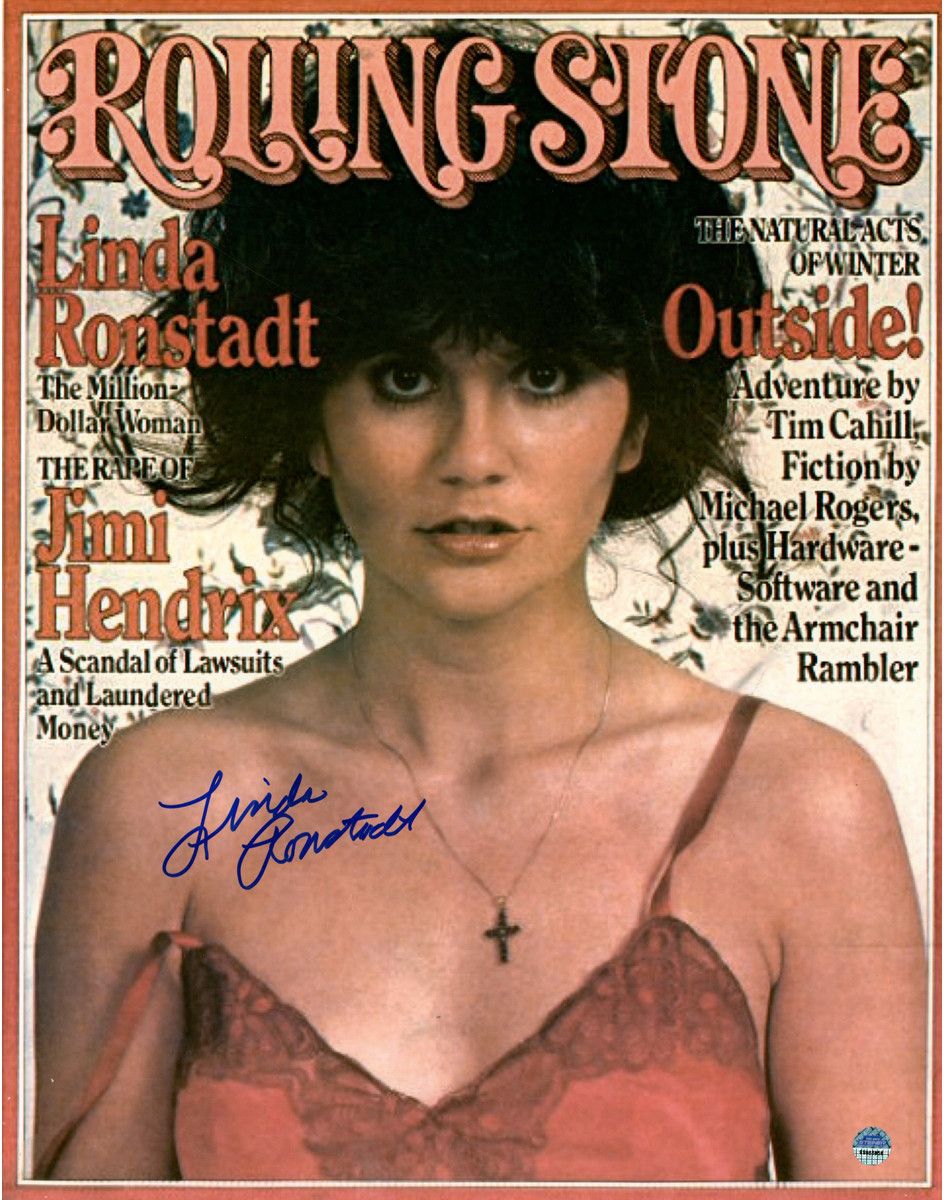

The series opens with period footage of interviews, musicians and still photos which pull together the cultural ethos, the allure of youth and creativity, the sense of style and sex appeal it advanced.

It wrote about groupies, drugs and rock as an art form.

And that changed everything.

The series certainly is obliged by constraints of space and time to skim or gloss over some aspects, but there is a candor in the old footage and there is no doubt the Stones' political coverage and New Journalism was more important than the Plaster Casters.

And yes, you do see some the Caster's working method and their art.

.

Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge, Prime TV Tuesday March 6, 9.35pm

Letter from the Editor, published in the first issue

Letter from the Editor, published in the first issue

You're probably wondering what we are trying to do. It's hard to say: sort of a magazine and sort of a newspaper. The name of it is Rolling Stone, which comes from an old saying: "A Rolling Stone gathers no moss." Muddy Waters used the name for a song he wrote; The Rolling Stones took their name from Muddy's song and "Like A Rolling Stone," was the title of Bob Dylan's first rock and roll record.

We have begun a new publication reflecting what we see are the changes in rock and roll and the changes related to rock and roll. Because the trade papers have become so inaccurate and irrelevant, and because the fan magazine are an anachronism, fashioned in the mold of myth and nonsense, we hope that we have something here for the artists and the industry, and every person who "believes in the magic that can set you free."

Rolling Stone is not just about music, but also about the things and attitudes that the music embraces. We've been working quite hard on it and we hope you can dig it. To describe it any further would be difficult without sounding like bullshit, and bullshit is like gathering moss.

— Jann Wenner

Graham Dunster - Feb 27, 2018

Thanks for the heads up!

Savepost a comment