Graham Reid | | 4 min read

About two-thirds the way through this revealing, sometimes disturbing and occasionally (unintentionally) funny 95-minute doco Martin Phillipps is seen going through his scrupulously archived Chills clippings and comes on one from '92 written when he returned to New Zealand after announcing onstage in the US – to the surprise of his bandmates – that the Chills would be no more.

He reads from the article the following, “the Chills were the great white hope of Kiwi rock . . . now become a joke”. He stares into the middle-distance and although that piece was written 25 years previous – it was by me and is here if you care to read it in its entirety – he seems as shell-shocked today as he was then.

“Just . . . . blank,” he says to no one in particular.

And yet back then, having crawled home broke, battered and to an uncertain future, worse was to come: alcohol dependency, a drug addiction which damaged his veins, Hep C which ravaged his liver, various resurrections of the band with different members and some tours less successful than others . . .

With parallel narratives – Phillipps today getting the prognosis of early and imminent death then going off the booze and taking treatment, the story of the Chills' rise and demise and rise again – this is a compelling look at a man whose music touched scores of thousands at home and abroad but for whom the vision was fundamentally flawed.

With parallel narratives – Phillipps today getting the prognosis of early and imminent death then going off the booze and taking treatment, the story of the Chills' rise and demise and rise again – this is a compelling look at a man whose music touched scores of thousands at home and abroad but for whom the vision was fundamentally flawed.

In the words of a school report, “Martin doesn't play well with others”.

Band members attest that he could be uncommunicative, self-centred and carried a lot of deep emotional baggage.

He admits as much himself at one point, that he was “not going to sacrifice the quality [of the music] for a bit of team spirit”.

Not a team player then, but undeniably a man with a musical gift which is rare.

The songs which punctuate the doco -- from the ethereal Pink Frost and coiled rage of I Love My Leather Jacket to the sublime Heavenly Pop Hit and beyond -- springs to life again and, especially in the contexts here, are revealingly autobiographical.

His vision for the Chills was one that he couldn't share however, at least not in words with those who he actually needed to realise the music in his head. Bassist Justin Harwood says he didn't know if he was needed or expendable, other say something similar.

His vision for the Chills was one that he couldn't share however, at least not in words with those who he actually needed to realise the music in his head. Bassist Justin Harwood says he didn't know if he was needed or expendable, other say something similar.

Drummer Jimmy Stephenson, just 17 and keen when he joined one of the many line-ups, is in tears when he says now that he still hasn't come to terms with what happened.

And what happened, all too frequently, was triumph followed by opportunities lost, yet another line-up change and sometimes genuine tragedy.

“There's a lot of tragedy in the Chills story,” says Doug Hood who was there at the start with Looney Tours and taking the band on the road . . . and was badly injured in a car crash they were all lucky to survive.

Neil Finn speaks of the Chills music having longing, alienation and joy, and some of those are qualities which Phillipps reveals – sometimes unwittingly – in contemporary interviews where he is coming to terms with the possibility of death and cleaning out his house which is a meticulously organised collection of comics, records, books, DVDs, VHS tapes, toys and junk.

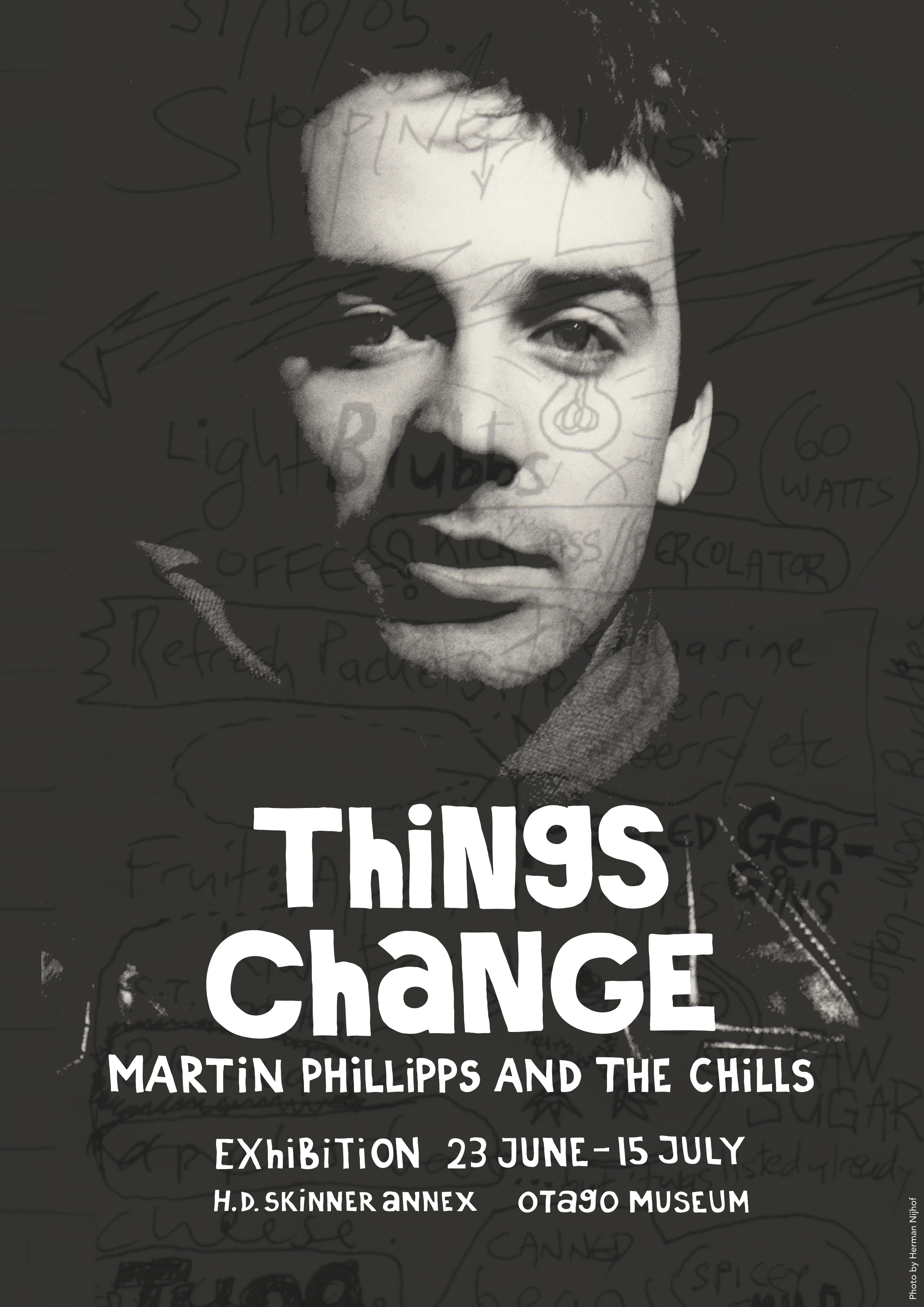

The cleaning out is cathartic – he even kept his drug paraphernalia in a tidy wee box just as he kept odd children's toys – but also a chance to contribute to an exhibition of the Chills and his artwork and memorabilia which was mounted in Dunedin.

The cleaning out is cathartic – he even kept his drug paraphernalia in a tidy wee box just as he kept odd children's toys – but also a chance to contribute to an exhibition of the Chills and his artwork and memorabilia which was mounted in Dunedin.

But what comes through everywhere as a strong subtext is Phillipps' need to be understood and to explain.

It has been evident when I have interviewed him and others would say the same, he often gives himself away unintentionally, his comments more revealing than he perhaps realises (“team spirit”?) and yet he was also battered by expectation after their early commercial and critical successes (they were the “great white hope of Kiwi rock” as I once wrote) and of course the industry in which he worked.

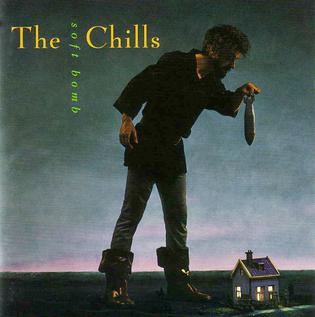

The sequences where producer Gavin McKillop virtually takes over making of the Soft Bomb album and the head of Slash laughing about wanting “pop shit this time, we're tired of this alternative stuff” show what he was up against from outside forces.

The sequences where producer Gavin McKillop virtually takes over making of the Soft Bomb album and the head of Slash laughing about wanting “pop shit this time, we're tired of this alternative stuff” show what he was up against from outside forces.

Martin Phillipps is a singular and, as this fine doco – in which Central Otago look astonishing – reveals, a solitary character.

Yet he is also courageous in his pursuit of pop perfection and although the subtitle here ends with “tragedy” things have been going well for him and the stable Chills since this doco was completed.

He is also courageous in letting the filmmakers access to his life behind closed doors, the wealth of Chills visual material and his archives, and of course letting the camera follow him through his medical process.

It is that need to be understood and explain, perhaps.

There are interesting and often insightful comments from various band members – Andrew Todd who was such a pivotal player notable for his absence though – and fellow travelers. But this remains Martin Phillipps' story and it is a strange, sad and sometimes uplifting one.

It is a compelling insight into a rarified and often disconcerting world where art and commerce, pop and personalities collided and the result was often an explosive fragmentation of ideas, psyches and people.

It's a must-see film, no doubt about that.

There is more on the Chills by way of reviews and interviews with Phillipps at Elsewhere starting here.

THE CHILLS: THE TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY OF MARTIN PHILLIPPS, a doco by JULIA PARNELL is now available on DVD and Blu-Ray

Angela Soutar - Apr 30, 2019

When I read about someone with such obsessive interests and dedication, single mindedness and intelligence and talent but not too much self awareness I instantly think - this guy is autistic [what was formerly called a person with Aspergers Syndrome.] Nothing to be ashamed of but would explain a lot about how he interacted [or didn't] with fellow band members. This may be too easy an explanation for the ups and downs of his life and the success or otherwise of the band in a damned difficult life choice - the entertainment industry - but worth bearing in mind in explaining that he didn't mean any illwill to others in The Chills.

SaveI assume he had a secure and happy upbringing as his father was the methodist minister for some years in the town I grew up in and was well regarded for his ability to communicate [especially with teens] and empathy with all. In fact while being in a minority in the town as far as his congregation numbered he could probably have hoovered up most of the inhabitants into his congregation who were active christians if they hadn't already been linked with other sects. The church of course gives one an excuse to rebel and be a bit different. I didnt have anything to do with Martyn as he went to a different school from me. A brave thing to allow your life to be displayed !

post a comment