Graham Reid | | 2 min read

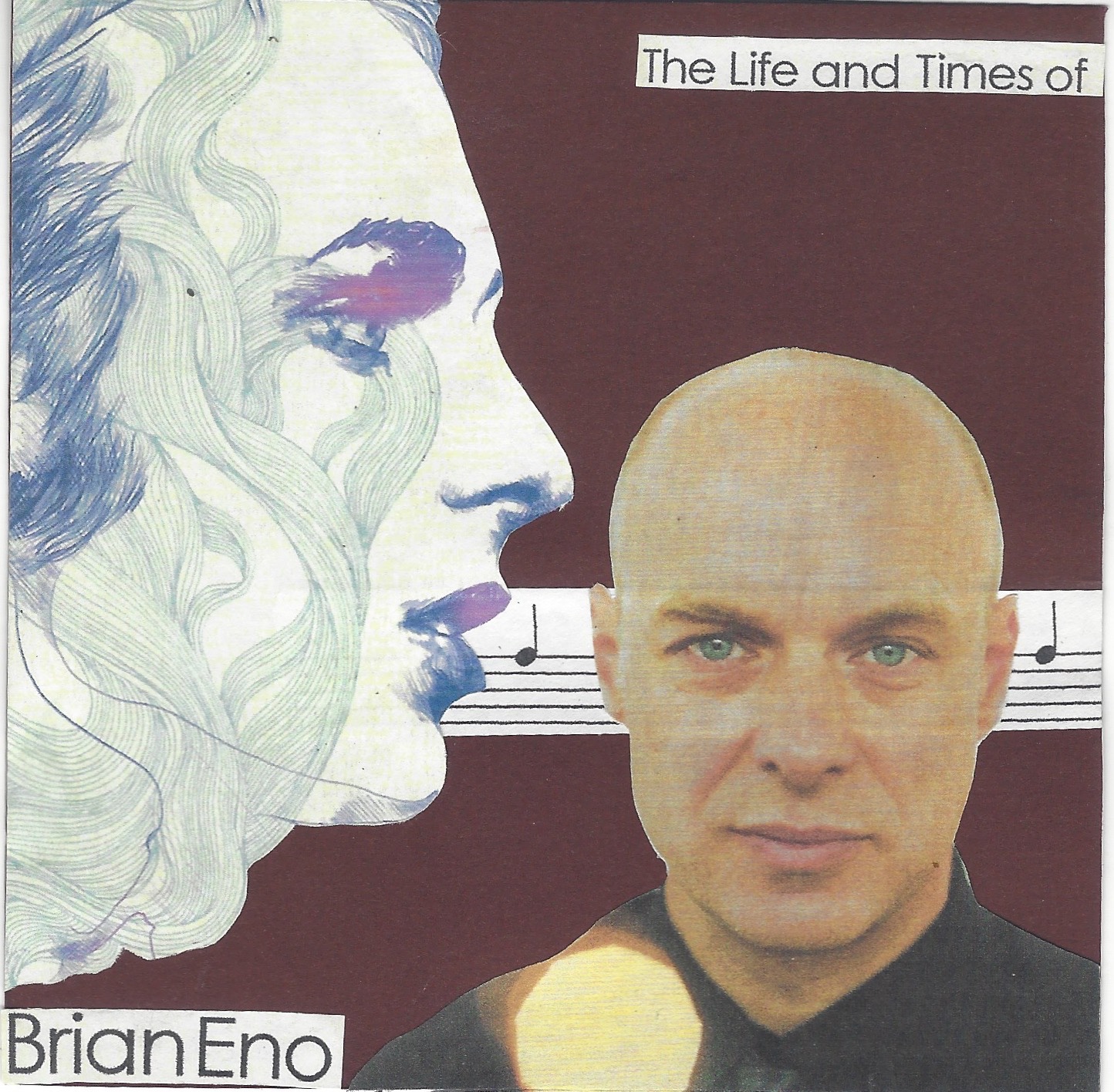

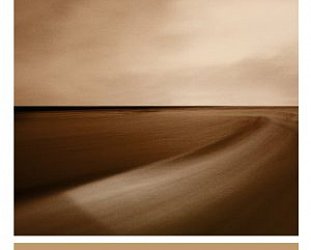

By happy chance recently I pulled out a vinyl album which has changed my listening habits for these past weeks. It was released 30 years ago but has always struck me as timeless: it is Brian Eno’s Music For Films and the austere, pale brown cardboard cover is mottled with age.

At any opportunity since I have gravitated to my cherished vinyl collection of Cluster, Harold Budd, Laraaji and other household names (ho ho ho) from the same era -- and most especially Eno who worked with Cluster (Moebius and Roedelius) and launched his own Obscure label in the 70s.

I have an embarrassingly large number of Eno and Eno-related albums I imported at the time, and they include obscure Obscure albums by Gavin Bryars, Michael Nyman and John Adams.

Eno was alarming prolific and experimental in the last half of the 70s: a couple of wonderful sonic landscape outings with King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp (No Pussyfooting and Evening Star, both recently reissued on CD); plus Discreet Music, Music For Airports, Music For Films and others.

The chief feature of these albums is a sense of space. This was, in every way, discreet music and the sober covers -- the Obscure albums coming in similar muted sleeves with explanatory notes and musician biographies in the manner of classical records -- said as much. Understatement was everywhere.

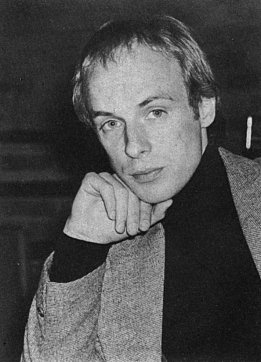

This was music from, or presented/produced by, a man who a few years previous had been on high heels in the flamboyant Roxy Music but whose new direction suggested pasting stamps in an album was an arduous physical activity.

It was the sound of space, silence, consideration and small ideas kept small. It was nothing like rock music where small ideas are rendered large.

The Eno/Obscure albums also weren’t that cliché of “less is more“: they were just “less is“. And that is more than enough.

I also re-read David Sheppard’s recently published but rather over-written and somewhat fruity Eno-bio, On Some Faraway Beach which reveals these voyages of aural discovery mostly came by accident and that egghead Eno would theorise them later.

Eno music at this time was also improvised (he was reading Luke Reinhart’s cult novel The Dice Man which seemed to provide the basis for his later Oblique Strategies game of randomly chosen cards with cryptic messages as prompts to creativity) and a small melodic idea would be slowed down, processed, bent, reused elsewhere . . .

The studio was an instrument and in that regard Eno was in step with producer Teo Macero who would edit Miles Davis albums together from studio sessions.

Listening to all these albums -- among them the mesmerising Sinking of the Titanic by Bryars in which distant orchestral music seems to disappear underwater -- it is extraordinary how beautiful and beguiling minimal sound can be.

On his better known 70s solo albums -- Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy, Another Green World, Before and After Science -- Eno embraced and perhaps invented an avant-garde pop approach.

On his better known 70s solo albums -- Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy, Another Green World, Before and After Science -- Eno embraced and perhaps invented an avant-garde pop approach.

But of this other work which ran in tandem (some of which he coined the term “ambient” for) there is nothing similar in contemporary music, and the main players -- Harold Budd, Michael Nyman, Jon Hassell, John Adams -- moved on to other and often louder things.

For this brief period here was music that valued the ethereal, allusive and elegant. It exhaled sound which could be hypnotic, repetitive and alluring. It was a rare and prolific time (eight Obscure albums in three years), but rarely acknowledged today. Shame.

Quiet is quite nice.

.

These Further Outwhere pages are dedicated to sounds beyond songs, ideas outside the obvious, possibiltiies far from pop. Start the challenge here.

radiocitizen - Mar 3, 2011

Go to More Dark Than Shark at moredarkthanshark for everything about Brian Eno...

Saveradiocitizen - More Dark Than Shark - Jun 29, 2011

The index of the Eno biography "On Some Faraway Beach" points to p.235 - there's a reference to Warren Cann and John Foxx of Ultravox! reading "The Dice Man" while recording their debut album (with Eno producing), but not Eno himself.

Savepost a comment