Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Resolution (Live)

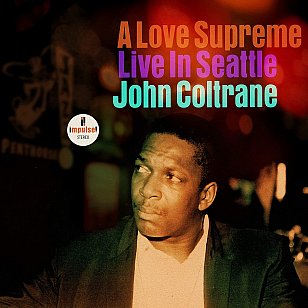

Even those with little knowledge of jazz know to nod sagely when trumpeter Miles Davis' Kind of Blue (1959) and tenor saxophonist John Coltrane's A Love Supreme (recorded in December 1964 and released a month later) are mentioned.

These albums transcend the genre and -- the Davis in particular which remains the best-selling jazz album – are often on the shelves of those who find jazz difficult or boring.

You wouldn't say that about either of these albums however: the Davis is warm, poised and approachable, and the adjective casually but appropriately applied to A Love Supreme is “spiritual”.

When Coltrane's album was released, he was a 20 year veteran who was with Davis for Kind of Blue and had played with Thelonious Monk. He would die at 40, a mere two years after the album's release but his avant-garde work in those final years alienated many for whom A Love Supreme was his most most sublime musical and intellectually towering achievement.

The album was a four-part suite recorded in one session with minimal overdubs (“This is the first time that I have received all of the music for what I want to record,” he told his composer-pianist wife Alice) and the liner notes and his poem made clear the and purpose.

They spoke of his gratitude to God, the inspiration for all things: “This album is a humble offering to Him”.

The four parts were titled Acknowledgement, Resolution, Pursuance and Psalm, the first working off the pulse of a hypnotic, four-note, anchoring bass over which at one point Coltrane gently chants the syllabic “a love su-preme”.

If the two central sections are more assertive and demanding for the casual listener – in a way Davis' Kind of Blue isn't -- the final part is reflective and gloriously elevating.

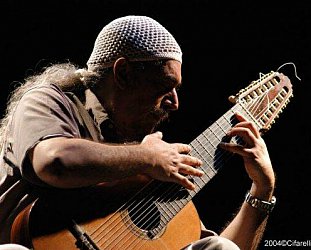

Coltrane and his band – pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones, known as his “classic quartet” – only performed the suite live twice: in July 1965 at a jazz festival in Antibes, France (it was included on the expanded, 2002 double CD reissue of the album) and in October that year at a Seattle club.

But even by the time of those appearances, Coltrane was pushing the music into more progressive and harder directions as witnessed by the recording in France where even the opening passages have an urgency beyond the studio recording.

The recent release of a private recording of his Seattle appearance – which has free form pieces interpolated between the parts of the suite – confirms how he was rapidly moving into more discordant, exploratory and avant-garde territory: the quartet now expanded for the date with the addition of fellow tenor player Pharoah Sanders (also a spiritual seeker who had become a permanent member of the group) and a second bassist, Donald Rafael Garrett.

Ascension in Seattle -- now stretched out to three times the length of the seven minute studio recording -- is established by Tyner, arco bass and busy percussion for five minutes before Coltrane's entry to pick up and tease apart – and some might say destroy – the memorable melody.

Ascension in Seattle -- now stretched out to three times the length of the seven minute studio recording -- is established by Tyner, arco bass and busy percussion for five minutes before Coltrane's entry to pick up and tease apart – and some might say destroy – the memorable melody.

Some will hear Sanders and Coltrane facing off like street fighters, Jones pushing them with explosive drumming. Many who loved the understatement of the original album will cower in the corner.

The unconstrained fury and energy in Resolution and Pursuance are leaps into the emotional abyss beyond the familiar studio version although Psalm remains a place of rest and consideration.

This release is another of a few recent rediscoveries of Coltrane's work coming to light: released in 2018, the album Both Directions at Once was a previously unknown studio session from 1963 and the following year another long lost studio session emerged as Blue World.

The former was wonderful, the latter less so.

A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle is, of course, an extraordinary album and a valuable historical document . . . but only if you come to it backwards from the overwhelming avant-garde of Ascension of later that year and his subsequent, demanding late career albums.

Alice Coltrane – whose own meditative and spiritual music has underground a rediscovery in the past decade – said that when her husband moved into avant-garde music he lost many followers but there was no way he could go back.

“What he had done often became obsolete the next day . . . from A Love Supreme onwards we were seeing a progression towards higher spiritual realisation”.

And as is so often the case, not everyone who started down that path with him could stay the course.

Any innocent civilian who has managed to be approvingly mute when A Love Supreme is mentioned should know they can now be blindsided by, “So, which version do you prefer?”.

.

John Coltrane's A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle is available now on viynl and CD in selected stores.

And on Spotify here.

post a comment