Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Impressions

When Thelonious Monk said “freedom and jazz go hand in hand” he was making a political observation, but also telling us something about the nature of jazz creativity.

Jazz allows its creators a freedom unavailable in most other musical idioms.

But, as with Abstract Expressionism, the far reaches of jazz creativity can leave the audience behind.

Those who want identifiable images and familiar sounds are not going to be comfortable with the more shapeless and difficult expressions.

No one says Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz of 1960 is easy but it did signal a new approach, and one of those on that album -- the saxophonist, bass clarinetist and flute player Eric Dolphy – understood the possibilities that free playing and freedom offered.

Similarly John Coltrane who began to extend his playing into areas which drew the famous description “sheets of sound” at one point.

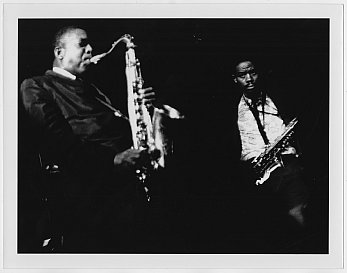

In 1961 Dolphy joined Coltrane's famous band – drummer Elvin Jones, pianist McCoy Tyner and bassist Reggie Workman – and appeared with them at New York's Village Vanguard and the Village Gate.

The Village Vanguard albums recorded live in November '61 are considered among the best jazz has to offer from that period when there seemed to be an urgency as so many jazz musicians fell victim to heroin and the jazz life.

There was so much activity – on stages and in the studio – that previously unreleased and often unknown recordings keep coming still come to light, among them Coltrane's Both Directions at Once recorded in March '63 and the live A Love Supreme from October '65.

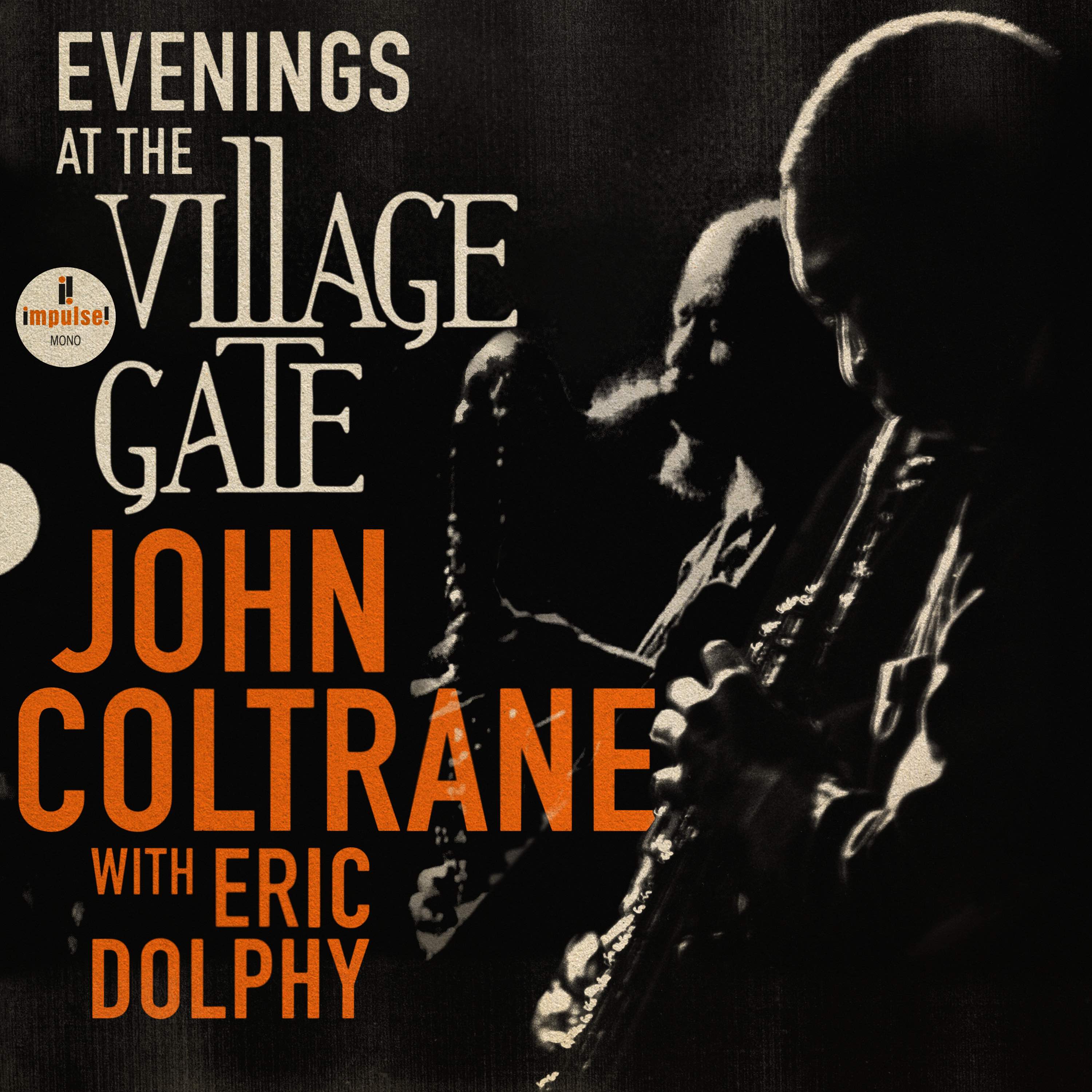

Now another live recording, Evenings at the Village Gate, appears from the vaults of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts: it is of Dolphy and Coltrane in August '61 with Coltrane's legendary group.

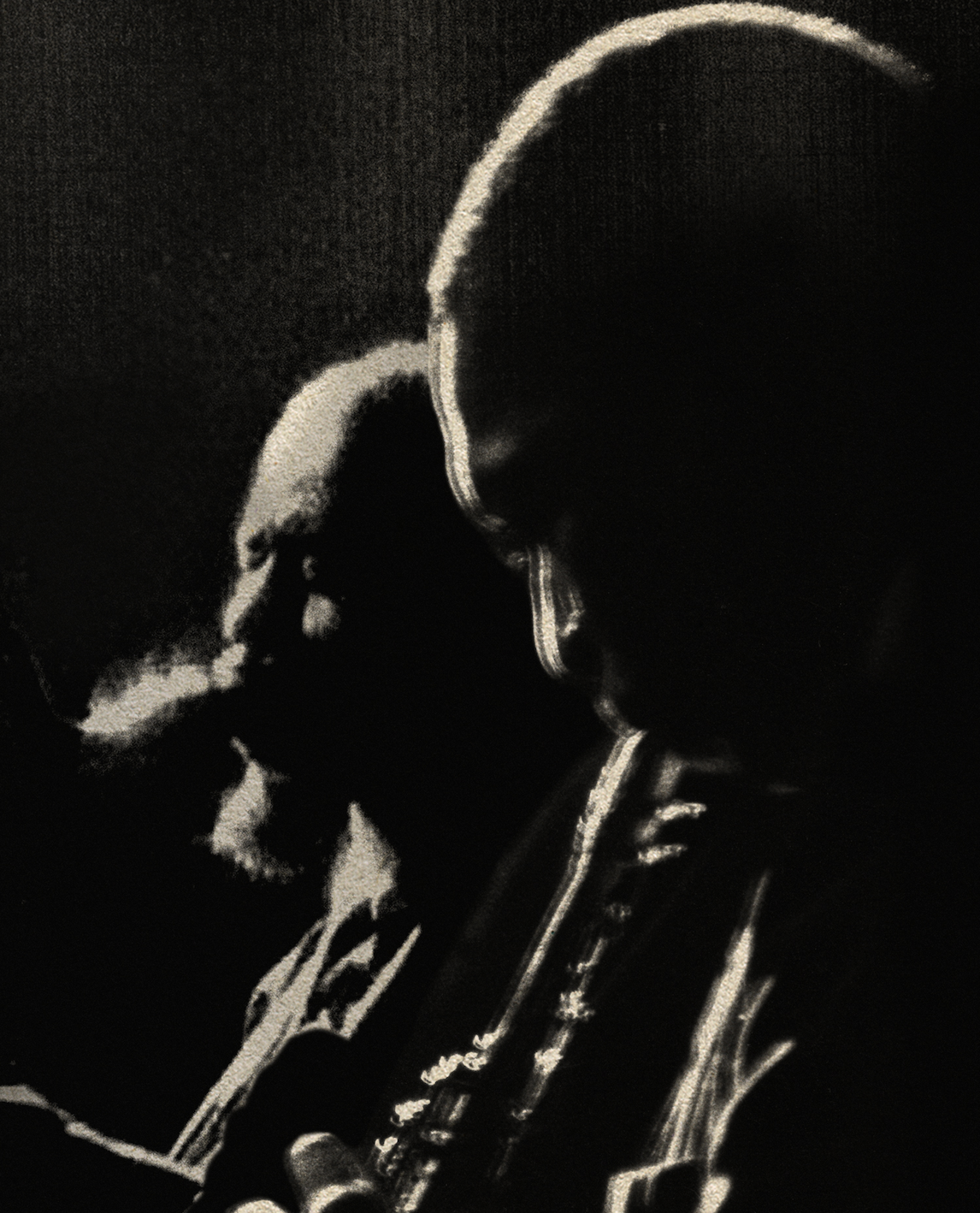

Coltrane and the younger Dolphy were kindred spirits, seeing how far they could take improvisation, but inevitably many critics and jazz aficionados didn't go with them as they pushed into areas of demanding creativity.

Coltrane and the younger Dolphy were kindred spirits, seeing how far they could take improvisation, but inevitably many critics and jazz aficionados didn't go with them as they pushed into areas of demanding creativity.

Dolphy had done the mileage but was also an outsider: the word “out” appeared in three of his album titles, notably his outstanding Out to Lunch recorded just four months before his tragically early death in '64.

On Evenings at the Village Gate they go out there: Greensleeves and My Favourite Things (Dolphy on flighty flute weaving around for almost seven minutes before Coltrane enters) stretch to 16 minutes; Coltrane's monumental Africa (with bassist Art Davis in the line-up) is a kaleidoscopic 22 minutes with passages of furious intensity alongside quieter sections by Tyner and Davis. It is the only known live recording of it.

The Dolphy/Coltrane association was productive but didn't last, each man heading in their own directions: Dolphy off to what he thought would be more challenging pastures and receptive audiences in Europe.

The Dolphy/Coltrane association was productive but didn't last, each man heading in their own directions: Dolphy off to what he thought would be more challenging pastures and receptive audiences in Europe.

Coltrane went deeper inside himself to find a spirituality which would emerge on A Love Supreme in '64.

The music they created at the Village Gate is sometimes demanding but it captures a period when, hand in hand, jazz and freedom channeled the joys and pain of life.

.

You can hear Evenings at the Village Gate on Spotify here.

There is more about John Coltrane at Elsewhere starting here.

Jonathan Booth - Aug 7, 2023

What a great album. The personnel are on fire: John Coltrane; Eric Dolphy; Art Davis; Elvin Jones; McCoy Tyner; Reggie Workman. I'm not going to forget the clubs sound man - he sure knew his stuff - the right place to hang the one microphone to get the music recorded so well. It's a joy to listen to from start to finish.

Savepost a comment