Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Looking back now it is hard to recall how it all started and who we should blame – but suddenly in the mid-70s there they were, electric guitarists spitting out notes faster than shells from an Uzi.

“Fingers scampering across the fret board like a mouse on Meth,” was how Playboy described a 1975 Jeff Beck album, and the sheer speed of warp-factor five guitarists like John McLaughlin was breathtaking. Not only a lot of notes per second . . . but lots of seconds. Minute after minute of them, which sometimes added up to hour after hour.

Impressive enough – but hard to take. They called it fusion, and it was the beginning of jazz being melded to rock. It was also the end of an audience after a couple of years of it.

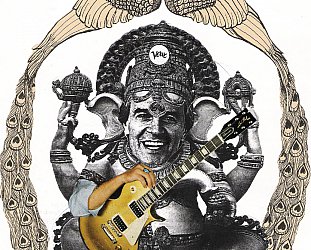

“Ah-ha, the old fusion curse,” laughs American guitarist John Scofield with the weary air of a man who saw it all.

“I loved John McLaughlin but there were all those guys who copied him and got into that show-off think. I never wanted to play incredibly fast. Well, I did actually if I was honest, I just couldn’t.

“But that wasn’t what moved me in music, although funnily enough the first gig I ever really had was with [drummer] Billy Cobham’s big fusion band playing all that jazz-rock stuff with huge amplifiers and massive effects pedals.”

If Scofield’s recollection of those fast’n’furious days sounds a little schizophrenic, pity anyone who tries to piece together the career of this much acclaimed musician: three albums with Miles Davis and two with Kansas City blues pianist Jay McShann; guest appearances at every major European and American jazz festival and minor New York club; performances with gumbo-funker Dr John; duelling guitar with Bill Frisell and Pat Metheny; and more than a dozen albums under his own name.

When Scofield plays jazz, he rocks out. He has covered songs by New Orleans’ The Meters and his song Twister, which appeared on the Second Sight album by his bassist Marc Johnson in ’87, was just an excuse for the boys to kick around Twist and Shout one more time.

Scofield is part of the hard core of guitarists who reshaped the meltdown of jazz, rock and r’n’b in the 80s. They kept it under tighter rein than the hyperactive fusion of the previous decade but, in the rush to acclaim jazz artists like trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, have largely gone unacknowledged.

Maybe Scofield is too rock for jazz and too jazz for rock, but alongside the fractured guitar antics of James Blood Ulmer, Sonny Sharrock’s jack-hammer playing the melodic sheen of Pat Metheny and hard-to-figure genius of Bill Frisell, Scofield is redefining the language for the guitar.

And having fun with it, too, as song titles like The Beatles, So Sue Me, The Boss’ Car and Farmocology suggest.

Despite his poll-winning profile Scofield can probably only reckon on worldwide sales of 120,000 for the album. Put that against sales for an average rock artist in Australia which sells twice as many and you can see why Schofield gets his income from live work.

But in jazz, live is what it is all about. It is music from the bandstand given its knife-edge unpredictability by the musician being composer and performer simultaneously. No two nights the same - and often no two nights in the same town.

Scofield is always solidly booked most of the year with concerts in Asia, the States, Europe and Britain.

He has even been to New Zealand - a workshop/performance tour in’79 with bassist Steve Swallow when he took time out to record with local musicians for Frank Gibson Jnr’s Parallel 37 album, and then again in 91 with his own band of Marc Johnson (bass) and Bill Stewart (drums).

Scofield enjoys himself, but seriously. Silly song titles on his album sure (his wife thinks them up, he admits), but these same albums have also seen him experiment with recording most of the instruments himself (Electric Output of ’84 when he was still with Miles Davis’ trio) and in quartets and live recordings.

He’s played with British jazz composer and orchestra leader Mike Gibbs, and New Orleans funk artists. He’s explored drum’n’bass and old fashioned swing. And rock.

Scofield goes around in his music and it’s that quality which set him, and others, apart from the neoconservative school of players who came through in the 80s.

“Not to put guys like Wynton [Marsalis] down,” he says, “but the guitar thing has been new, whereas the language Wynton is playing is still basically that early Miles Davis/Freddie Hubbard vernacular. There’s nothing wrong with that I love it too – but on guitar we’ve adapted our stuff using rock’n’roll techniques. It’s pretty different all right.”

And Scofield himself is pretty different – a middle-class white boy from a bedroom community in Connecticut some 50 miles from New York City – “hardly the home of jazz-blues guitar,” he laughs.

Now past his mid-50s he reflects on one of those fairly typical ’burbs upbringings which meant the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show back in ’64, turning on to pop-rock and then, inexplicably, being drawn to playing blues guitar by the time he was 15.

“My parents weren’t musicians and I got a few lessons from a guy down the street who was a dance band guitarist. Then I met another guy who was a bebop fanatic. He wasn’t that good and anyway I was playing in rock bands and becoming this huge B.B. King fan.

“As a kid I used to take the train into NYC to hear great blues players like Otis Rush, then I discovered jazz guitarists like Jim Hall and Wes Montgomery. Those clubs had an 18-year-old drinking age so I had to get a phoney ID. When I was 16 I had a draft card. They were easy to get, nobody wanted ‘em. They were burning those things.”

But in his late teens, as Scofield looked around for role models, he couldn’t find them among the jazz generation.

“My theory is that any serious musician on pop instruments like guitar, bass or whatever starts out in rock bands, but if they are in any way serious about their instrument they can’t avoid or overlook jazz.

“In the 60s the musicians I met were all into r’n’b-oriented rock but were listening to people like [jazz organist] Jimmy Smith or Wes Mongomery on guitar – all that straight-ahead stuff.

“But you just didn’t hear hard-edged jazz guitar back then. Trumpeters could look to Miles, Freddie Hubbard or Lee Morgan. But on guitar there just weren’t too many of that generation.”

To compensate for having to go home to his quiet suburban town “where maybe two people in the whole place liked the music I liked,” Scofield enrolled in Berklee School of Music in Boston and immersed himself in music.

Then came fusion and the call from Billy Cobham to go on the road and play breakneck guitar.

It was ’75, and for two years he did the “mouse on Meth” music like Beck, McLaughlin and others. But in the hotel room afterwards he was practising on standards like All The Things You Are and listening to bebop tapes by saxophonists Charlie Parker and Joe Henderson.

By the time fusion had disappeared up its own artifice and ceased to be little more than an endurance test, Scofield was immersed in enough blues and jazz to step in the studio alongside people like trumpeter Chet Baker in ’74 and ’78.

Baker was on one of his comebacks from drug rehabilitation and Scofield counts himself lucky he “only ever heard him play marvellously.”

Quietly, Scofield was making his way into the world of more studied jazz – but still jumping at offers to have fun alongside old Kansas City pianist Jay McShann and his band.

“I played gigs with those guys and it was just such a thrill to be around them...people like (tenor saxophonists) Paul Quinchtte and Buddy Tate...just great experience.

“I’m a huge jazz fan but really did start with the blues. I remember hearing a Louis Armstrong record when I was about 10 and not knowing what it was but being deeply moved by something in the music.”

On his own Electric Outlet album of ’84, he indulged that love of blues in the short King For A Day, a tune which paid homage to the Kings of blues, BB and Albert.

It was after recording with Billy Cobham, an ex-Miles Davis player, that Scofield was sought out by Davis who, like Baker, was edging his way back from years of indolence and drug dependency.

When Davis wanted to get a tough urban blues sound on his Star People, Decoy and You’re Under Arrest albums, he had Scofield’s aggressive guitar as the foil.

“Miles was really into interplay at that time,” says Scofield. “Later some of what he did involved less of that and more into overdubbing in the studio with [producer/writer] Marcus Miller.”

Scofield also appeared on Davis soundtrack to Siesta, but admits he really can’t remember it. It was pieced together by Miller later and his contribution on acoustic guitar was done without him hearing much else of the music.

These days he is mostly out with his own bands – and recording. He’s guested on a number of albums including one with the bop pianist McCoy Tyner, once a member of John Coltrane’s seminal 60s group, and for his own Time On My Hands in the mid 90s bassist Charlie Haden, drummer Jack de Johnette - and “my old buddy from Berklee, saxophonist Joe Lovano” with whom he still plays and tours with regularly

These players of different generations (Haden with an extraordinary career going back in the 50s, de Johnette a product of the 60s and Scofield and Lovano of the 70s) are like members of an elite club, familiars in a demanding idiom where a meeting of equals brings out the best in each.

And Scofield is still exploring.

It is part of the unwritten contract of jazz that the music is often its own, and the only reward. Nobody cashes in on jazz because there’s not much cash there in the first place. But John Scofield has made it as high as it is possible to go.

Unlike most jazz musicians, he works all the time.

Even as far back as 1982 however – before the Davis, Haden and Tyner connections - Sam Freedman would write “it has been a perfect and ironic misconception to identify John Scofield by his associations,” then tick off a long list of musicians he had worked with.

More than two decades on, the list is even more impressive, but Scofield is not only definable in his own terms. In the mid 90s there was a Scofield album where the title said it all: Meant To Be.

post a comment