Graham Reid | | 4 min read

These days, Keith Jarrett gets as much space, sometimes more, in jazz encyclopaedias as the great saxophonist John Coltrane. That irritates some people, it would be like Van Morrison getting more than Sam Cooke in a dictionary of soul.

But there’s a reason: they’ve lived longer, done more.

When Coltrane died in 1967, he’d had an effective playing career of just over 25 years.

By ’67, Jarrett had already served in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, the Charles Lloyd Quartet, had put in the hard yards in New York clubs, and hadn’t really started.

Now, 30-something years later, he’s still at it. Sort of.

Jarrett’s new album, The Melody at Night, With You is his first in four years, and for someone who was flicking single, double and multi-unit packages with alarming regularity, his silence and absence from performance – has been uncharacteristic.

Again, there’s a reason; in 1996 this keyboard genius (piano, harpsichord, you name it) staggered from an Italian stage exhausted, although that was nothing unusual. Concerts often saw him wrestling with his muse and punctuating the lovematch-grudgematch with audible groans and moans. But when he cancelled all upcoming concerts and withdrew to his New Jersey home there was clearly something seriously wrong.

Jarrett learned he was suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome.

“Basically, I

couldn’t do my work,” he told Time last year.

We can’t begin to imagine what that must

feel like for a musician, especially one as driven as Jarrett. All those years

of learning and playing, all those months of discipline and practice just to

play Bach’s Goldberg Variations on harpsichord or Mozart piano concertos, all

those decades of improvising in clubs then concert halls locating notes and

chords somewhere in a pure stream of possibilities...

Locked away in New Jersey, all that music

was imprisoned in his head unable to find release.

Genius often pays a terrible price -- but

sometimes so do those who have to work alongside it, interview it, and put up

with its tantrums and demands.

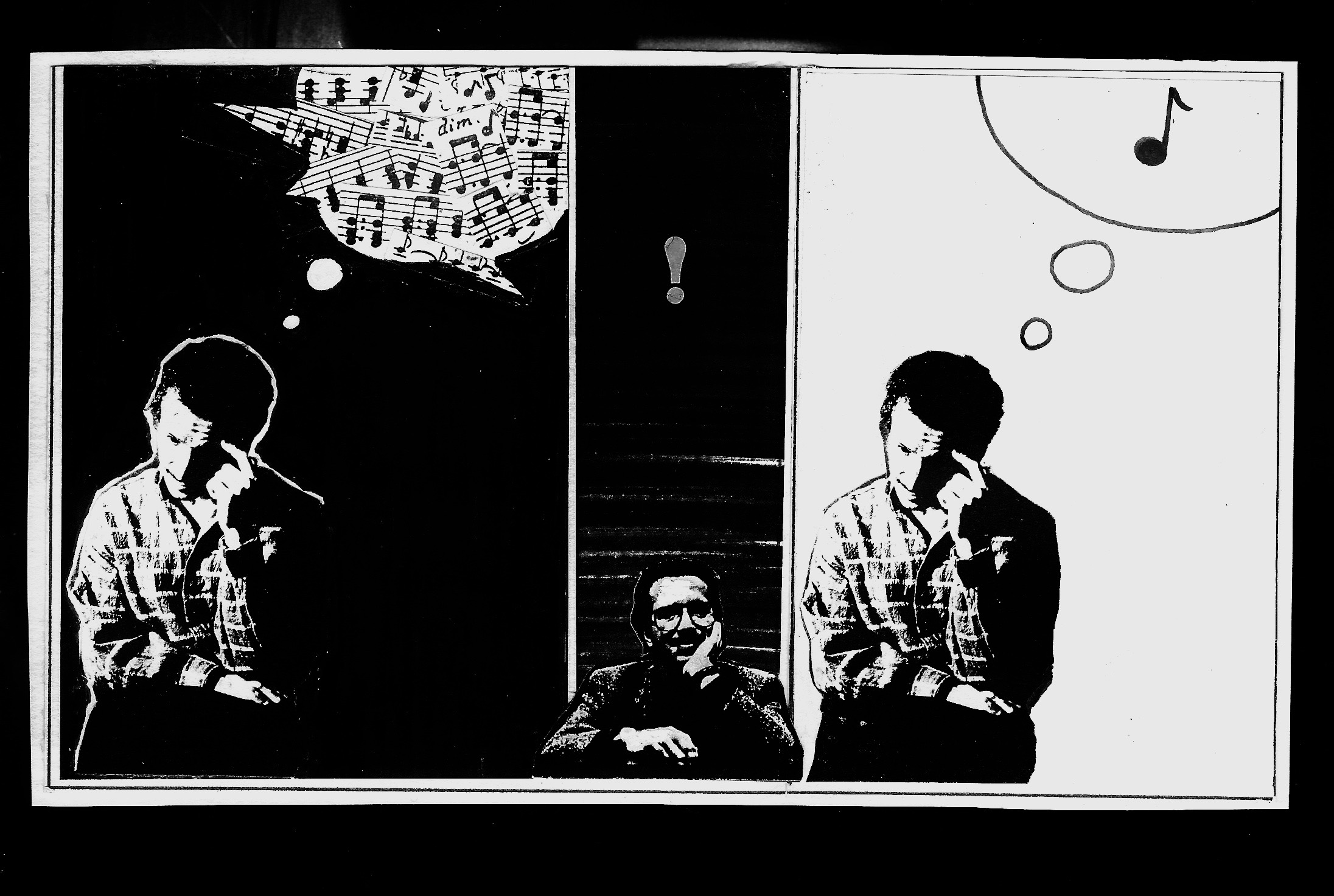

Jarrett, especially in his early career, exacted a high price from those around him. There are numerous profiles and interviews from the mid 70s which could run under the heading: Portrait of the Artist as Young Arsehole. But to be fair, no one should ask musicians be nice people, just that they deliver great music.

Jarrett, mostly, kept his part of

that contract.

Before being signed to ECM, where he has remained since 1971, he played with Miles Davis, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden, Paul Motian, Ron Carter, George Benson (before he claimed the jazz middle-ground), Gary Burton and many others in an impressive roll call. But it was the mid 70s when Jarrett really hit his stride.

He would take the stage with the barest

of musical ideas then decant the music from within, with sometimes profound

results. His Koln Concert album from 1975 had the unmistakable stamp of

genius and he has often repeated the feat since.

It wasn’t all brilliance however: as one

encyclopaedia tartly notes of his 1967 double album, Spirits, which found

him on various saxophones, Pakistani flutes, Indian table drums, shakers and

glockenspiel: “The sheer momentum of early success allowed him to experiment

freely, but it has also allowed an unusual and not always desirable licence to

experiment in public. Many artists might have attempted the material documented

on Spirits; few would have expected to see it make the

shops.”

Jarrett has been prolific: ECM lists over 50

titles, although when he was delivering things like the 10 album Sun Bear Concerts crate in the late 70s he could fairly be accused of uncalled-for

gigantism.

In the 80s and 90s he didn’t slow the pace but self-critical faculties and refinement kicked in. He worked in beautiful trio settings returned to daring interpretations of standards (all bearing his cerebral fingerprinting) and turned attention to the classical repertoire. The late 80s/early 90s found him at his best.

But that night in Italy it came to a

grinding halt, the music now trapped in his head.

The Melody at Night, With You began when he started taping in his home studio in December 1997 on a recently overhauled Steinway. He found by using mic placement and through the new sound of his piano, he could play with welcome softness but, because of weariness, only for short periods.

He discovered, as many have before, that less was

more. He says he detoxed from chord patterns and harmonies that came from the

brain not the heart.

He discovered, as many have before, that less was

more. He says he detoxed from chord patterns and harmonies that came from the

brain not the heart.

The album is of standards – Gershwin’s I

Loves You, Porgy, Someone to Watch Over Me, and My Wild Irish Rose

among them – shorn to their melodic essence. He has abandoned embellishment,

there is very little improvisation, yet has focussed with passionate intensity

on every note.

Because of the weight of his output – few would have signed up for the 1994 six disc set At the Blue Note which captured three consecutive nights in New York – Jarrett has been going past those unable or unwilling to keep up.

But he’s different now, and Melody is one to return for.

You sense pains of all kinds have been assuaged. As with most

works of art, it is as much what you bring to it as the artist does. It’s

certainly one for quite consideration and contemplation.

As Terry Teachout put it in Time:

it’s a record to be played late at night, when the streets are empty, the air is

still and you feel like thinking about what might have been or could

be.

And, I might add, wonder what Jarrett must have been going through in those darkest of days.

.

Greg Fleming - Apr 19, 2010

His sense of timing is almost tidal. The Jarrett record I most return to.

SaveCharlie Haden and Kenny Barron's Night and The City is another along similar lines and almost as special.

Ralph c - Mar 27, 2024

Listen to Shenandoah. It's magnificent

Savepost a comment