Graham Reid | | 3 min read

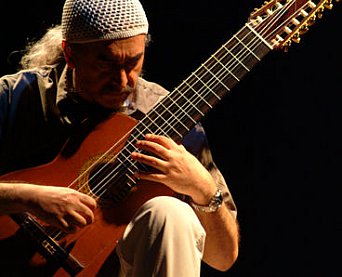

They say truth is where you find it. For Brazilian multi-instrumentalist and composer Egberto Gismonti it was there among the Indian peoples of the remote Xingu region of the Amazonian jungle back in the late 70s.

For a month, far removed from the urban world he knew and with no common language other than music, Gismonti lived and played music with the Indians, particularly their chief Sapain whose instrument, the jacui, was “a kind of flute that represents the spirit voice.”

“Before [then] my goal was music,” Gismonti told Robert Palmer of Rolling Stone in ’79. “But they opened the door for me. They played just feelings, they had no compromise. It wasn’t music, it was life.”

Gismonti is one of those characters whose music is too difficult to pigeonhole. He has recorded for ECM – the European jazz and contemporary classical label - yet his expansive talent for song writing, arrangement and classical composition (not to mention traditional Brazilian musics) means his albums can turn up in different sections of the musical supermarket.

That’s the price he pays for being wilful enough to learn classical music in Rio de Janeiro in the late 60s, conduct a pop orchestra in Paris, study composition with Nadia Boulanger and flirt with electronics in the States. But all that was before he joined a party of anthropologists and found himself sitting in the jungle playing the spirit sound.

Since then his ECM work – especially his own ’78 So do Meio Dia album which followed the Xingu sabbatical and the ’81 Folk Songs album with bassist Charlie Haden and Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek - have had strong folkloric flavours.

There are always a few Gismonti albums in specialty stores and they are, for the most part, very appealing as Gismonti bounces around the frets of his eight-string guitar, plays bamboo flutes or works out on an African thumb piano. Very melodic, too, if you are worried by that unusual-sounding cocktail.

Three albums from quite separate parts of his long career on the Carmo label (through ECM) illustrated the kind of diversity he was embracing before and after his jungle experience.

The Egberto Gismonti from ’73 has the man in charge of a vigorous jazz orchestra (and comes with arcane cover notes about cannibalism). It is variously engrossing and defiantly disconcerting as the musicians flick around on the free end of the jazz palette and work the same unnerving tensions as a Hitchcock soundtrack.

Circense from 1980 takes its lead from carnival culture. “In Brazil carnival is a synonym [sic] to confusion, disorder, mess ... no other country has ever been so proud of living under the sign of disorder ...”

The muscular and kaleidoscopic array of sounds on Circense is extraordinary as Gismonti writes for (and performs with) a quartet, hauls in a big violin/cello/saxophone crew when the mood takes him and rocks out on a Latin beat while Indian (from India) violinist Shankar (an ECM labelmate) adds his distinctive – and very un-Brazilian – sounds to the stew.

There are ballads and dances and Ta Boa Santa is supple Santana-in-Vegas (really 70s and quite neat).

Pieces like the long Matico adroitly match an eerie, stabbing string section with featherweight flute and voice. Circense may well be the only Gismonti album you need. It certainly offers the breadth of his scope.

Kuarup of 89 also takes its lead from celebration – that held for the dead by those Indians he lived with.

Unfortunately, the rather beautiful ritual retold in the cover notes is seldom matched by the music, which wavers between orchestral bits, snatches of guitar and so on.

The problem is perhaps that this is a soundtrack...and one to a film you’ll never see, let alone know the story of. Ask yourself, would you buy the soundtrack to an obscure film if you hadn’t seen the movie? Or even if you had?

Kuarup registers about there.

Since the early 90s he has largely disappeared from the radar although he has been enormously prolific: he’s up to about 30 albums under his own name but only a couple have been on ECM, he’s back where he started: big in Brazil.

So is Gismonti’s life more interesting than his music? That would be unfair.

His jazz work has been great ...but coming at these three albums from that angle means you’ll probably find some of this a bit over-rich (he can get really pompous with an orchestra).

For his jazz work find the excellent Folk Songs or any of his early 80s solo albums.

And of these three, Circense is well clear of the others.

Wretched False Set - Dec 24, 2008

Thanks for this rare English-language insight into Gismonti's work. A few years ago, some friends of mine who visited Brazil brought back his "Antologia", a 2-CD career retrospective from 2003. Ambitious, overstuffed, genre-defying, soulful, weird, dorky, virtuosic... you start running out of adjectives, and sometimes out of patience. I keep waiting for Gismonti to become American hipsterdom's Brazilian flavor of the month. Hasn't happened yet -- that could be due to poor distribution here, or because his proggy tendencies still relegate him to the Poor Taste bin stateside. Until Williamsburg kids embrace the 14-minute synthesizer solo, Gismonti would benefit from a good curator who can splice together a body of his work more amenable to US tastes. David Byrne, are you listening?

Savepost a comment