Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The night I heard Rod Stewart and Rachel Hunter had separated I went on a half serious, half parody, totally drunken Rod bender. I played all his Famously Scottish Songs (me‘n’Rod bellowing “here’s one Jacobite, won’t be home tonight” across 2am suburban streets), some of the old classics (I may have even dragged out the Jeff Beck album Truth for a blast of You Shook Me) and of course selections from the dodgy‘n’difficult Middle Years.

Mostly I played If Only from his patchy Vagabond Heart of 1990, an aching lament from a bad boy who’d been careless with love. Given the break-up it was prescient song and still moves me to this day. "If only I'd come home at night, instead of staying out for one more drink . . ."

Yes, Rod, even at his lowest points, could still tug a heartstring and milk a cheap sentiment. Which is why I’ll always give his albums, even now, a fair hearing. And usually come away disappointed, especially by those collections of highly marketable and seemingly popular standards.

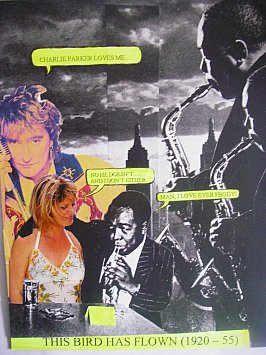

His last album of originals -- Human in 2001 -- was better than most although as always there was one real duffer on it, in this case the faux-soul of Charlie Parker Loves Me, written by that prat Marc Jordan. It’s an evil, objectionable song and hauls in the name of a jazz genius as a cheap reference to elevate mundane material.

Charlie Parker -- as with so many other great jazz names like Thelonious Monk, Sun Ra and whoever else hip young rock bands like to mentioning interviews -- has become that these days though, a name-check for people who’ve seldom, if ever, taken the time with his music.

But if you take the time, think about where and when Parker’s music came from, and consider that great man with an insatiable appetite for everything in life, you are forced as always to conclude . . . what music he made!

Take the word ”jazz” away if it’s a problem for you and just listen. The angular melodies which somehow make perfect sense, the floating bounce of his saxophone lines, the skittering across the rhythm section, the sublime romanticism sometimes . . .

Genius is a word used far too lightly these days, so let’s clear that one up: there are no genius DJs; Prince was gifted but not a genius; and rugby players? Sorry we’re having a serious conversation here.

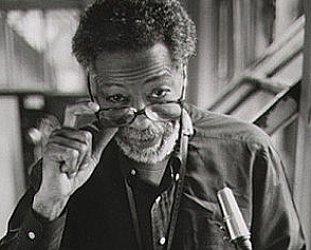

But alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, born in Kansas City in 1920, was a genuine genius. He heard music and its possibilities differently and rewrote the textbooks by simply getting up on bandstand and creating new forms.

He was only 19 when he discovered a different way to play the standard Cherokee and started turning heads in New York clubs, mostly because people simply didn’t get it. So Parker headed back to KC, joined Jay McShann’s band and continued experimenting by playing across bar-lines and creating a style which would eventually be named bebop.

Parker’s name, alongside that of trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie in whom he found a kindred spirit following year, is synonymous with the style.

Anyone coming new to Parker today has a problem: where to start on this all too short, frantic career which these days see around 100 CDs available? Start at the beginning then, and the budget-priced Ornithology: Classic Recordings 1945-47 (on the Naxos Jazz Legends series) is the perfect introduction. It opens with two recordings from his classic sessions with Miles Davis in March 1946 (the title track and A Night in Tunisia), then shifts back to Ko-Ko and Now’s the Time from the previous November (again with Davis and also Gillespie on piano and trumpet, with Max Roach, barely out of his teens, on drums).

What you can hear is a seismic shift in jazz consciousness. The time of big bands and swing orchestra was coming to close, this new music was pushing back the frontiers in the post-war years and young bebop musicians felt the old world was dead and a new one was ready to be invented every night on the bandstand. And that’s what Parker did.

The 18 tracks on Ornithology were recorded in a remarkably inventive two year period (akin to the Beatles between Help to Sgt Peppers) and created the template for bebop which in turn leads to hard bop and free jazz and so on.

Without Parker none of that might have happened. It was also remarkable that it happened through Parker.

He brutalised his body through constant work, junk, eating voraciously and in his passion for women. He borrowed money for heroin and never paid it back, but was such a gentlemanly genius and lovable rogue that most around him forgave him. During this early period he recorded Lover Man, included on this album, while practically comatose -- and yet in his convoluted, bizarre solo there is at least a notion that beauty was achievable.

Shortly after the session he collapsed and was eventually taken to the Camarillo State Hospital suffering a mental and physical breakdown. It might have been the end, yet his career a jazz resident genius was just beginning. His work heard in these sessions is astonishing (just listen to the speed and invention on Dizzy Atmosphere) and you can hear it in a heartbeat how jazz was being changed forever.

But Parkers’ enormous appetite for life was also an appetite for destruction. When he died of a seizure -- while laughing at a comedian on television – the doctor thought he was looking at the body of a man in his 50s. Charlie Parker – known to everyone as Bird – was only 25. Legend has it graffiti went up all over New York within days: “Bird lives“.

He does in the music he left behind and in the vision of jazz he allowed us. But as his friend, the clarinettist Tony Scott, once observed, “‘Charlie Parker opened the door, showed the world and then he shut the door behind him“.

Too soon at 35.

If only ....

post a comment