Graham Reid | | 15 min read

John McLaughlin: We Will Meet Again (from the album McLaughlin Plays Bill Evans, 1993)

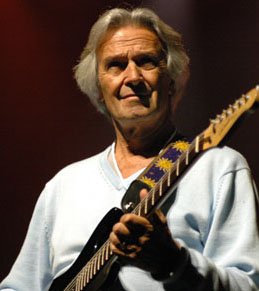

"I'm still at the beginning of my life and career,” says 67-year old guitarist John McLaughlin. “I don’t really think much about what I’ve

done, I don’t have much time to think about what I’ve

done.

“It’s

a worn out phrase, but today is a brand new day and there is a lot to do -- but

the great thing about music is you very quickly learn humility when you are

learning an instrument, because you very quickly see how incapable you are and

how obscure we are about our feelings.

“This

is one of the great lessons that music gives us. It brings us down to our real

size. And it doesn’t ever stop if you are musician,

whether you are 16 or 67 as I am now -- which seems very, very bizarre to me

because I am still 29. We hippies never make it to 30.”

And

the personable McLaughlin laughs very loudly.

While

you can understand where he is coming from in a broadly philosophical sense --

and a conversation with McLaughlin can be very broad and very philosophical --

it is hard to see his career as still at the beginning since it began exactly 60 years ago when an older brother gave him an acoustic guitar.

Encouraged by his mother, an amateur violinist, he took piano lessons at nine . . . . but his musical influences (aside from the epiphany of hearing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony on the BBC) were all blues guitarists. He fell in love with the blues of Muddy Waters and Big Bill Broonzy ("it grabbed me right away, it had a tremendous gravity") and he began learning chords from his older brothers.

He moved on to hard Chicago blues and when he was 14 heard Django Reinhardt and flamenco music.

Jazz started to enter his world (Tal Farlow was my real hero, he told Downbeat magazine in the early Eighties) and discovered Miles Davis albums, then Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane.

He moved to London from his home in Yorkshire and by 1964 he had worked with the jazz wing of the British blues revival as a member of Georgie Fame's Blue Flames, the Graham Bond Organisation (with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, later of Cream) and Brian Auger's Trinity.

In the years before the triumvirate of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page brought virtuoso playing into rock in the Sixties, McLaughlin had become a jazz-rock genius, but out on the periphery.

He edged towards the experimental when playing with avant-garde saxophonist John Surman with whom he recorded Extrapolation in 1969, and it was while jamming at Ronnie Scott's club he was spotted by drummer Jack DeJohnette who recommended him to fellow drummer and Miles Davis alumnus Tony Williams.

McLaughlin went to New

York to join up with Williams and organist Larry Williams to form Tony Williams' Lifetime, but within days was playing

on the Miles Davis’s seminal album of 69, In A Silent Way.

He

subsequently played on sessions for the Davis albums Bitches Brew, On The

Corner, Big Fun and A Tribute to Jack Johnson but was also in demand

as a session player (the Stones in rock, Wayne Shorter and others in jazz).

He

launched his solo career with two albums on a label run by the late Jimi

Hendrix’s friend and mentor Alan Douglas. The first of these, Devotion

in 1970, Douglas rightly considers the first jazz-fusion record. Of the second, My Goal's Beyond, Rolling Stone critic Robert Palmer wrote, "His solos on the first side reveal an awesome technique and an over-riding concern with shimmering melodic substance and harmonic ingenuity." (The album was re-issued in the late 80s when Bruce Lundvall established the Elektra-Musician label and grabbed it for his schedule.)

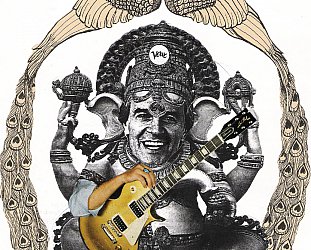

Then

McLaughlin established the Mahavishnu Orchestra in which set brain-finger speed

record for guitarists. This was jazz-rock fusion played with often blinding

intensity and energy, and in the early 90s Douglas observed, “McLaughlin

produced the kind of music that, had he lived, Hendrix might have pursued, a

far reaching spiritual celebration of rock, jazz, blues and Eastern-influenced

sounds”.

Ever

restless, McLaughlin collaborated with Carlos Santana; explored the new possibilities of the guitar synthesiser ("The synthesiser world opens the door to musical infinity," he told Time in 1975; and founded the acoustic

Indo-jazz group Shakti in the mid 70s with tabla player Zakir Hussain.

Critical opinion of their self-titled debut in '75 was divided: Gordon McLaughlin, when faced with the choice of playing the second side or throwing it out the window wrote, "Darn' thing must have sailed 70 yards".

The follow-ups Handful of Beauty ("this music takes you away into a land of the imagination, of bartered energies and climactic euphoria," wrote Downbeat) and Natural Elements ("the third and best Shakti yet, goes beyond anything McLaughlin has done in the past," said Tony Mattson in Craccum) found the guitarist at a career peak. In 1977 Downbeat rated him the fifth top player of the year.

But he was moving on (and back to his early love of flamenco) when he linked up with Paco de Lucia and Al di

Meola for a series of popular flamenco-jazz albums . . .

And

so his long career goes: playing with Indian musicians and jazz giants; playing again with Davis for the

Palle Mikkelborg tribute album to Davis, Aura, in the mid-Eighties; reviving Shakti

to great acclaim as Remember Shakti in the late Nineties; playing tough jazz

and deft acoustic ballads; and now touring in the 5 Peace Band of pianist Chick

Corea, drummer Vinnie Colaiuta, bassist Christian McBride and saxophonist Kenny

Garrett.

But

that is merely scratching the surface because behind that extraordinary breadth

of music is deeply intellectual, spiritually curious man who -- along with

Santana -- became a disciple of the spiritual leader Sri Chinmoy in 1970 (who

gave him the name “Mahavishnu” which means “divine compassion, power and

justice“).

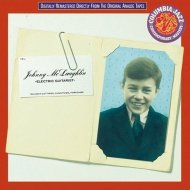

He

parted with his spiritual master in the late 70s and his acclaimed album Electric

Guitarist under the name Johnny McLaughlin (which had his teenage business

card on the cover) marked his coming out. One piece was an inspired reworking of Coltrane's Giant Steps with DeJohnette and Corea, elsewhere he was reunited with Williams' Lifetime, on Friendship he was joined by Santana . . . They were comfortable and relaxed superstar sessions which re-united McLaughlin with figures from his past and lead him out of the cul-de-sac of fusion.

But through his association with his guru and Indian musicians McLaughlin has explored a spiritual dimension in his playing. He also

learned an amusing, self-effacement.

“I

am just a working musician like anybody else and I am painfully aware of my own

incapacities and limitations,” he laughs. “A musician’s life is about that very

recognition. It is dedicated loving work, to quote another hippie phrase, and

that’s as good as it gets.

“When

you play you really have to be ready for, and open to, inspiration because that

really is the moment of truth. In performance inspiration comes, but if you are

not ready then it’s really a waste.

“The

instrument has to be part of your body and it has to be just a natural

extension of you, and in order for that to happen you have to spend hours with

your instrument, it is as simple as that. The instrument becomes part of your

psycho-physical body so when inspiration comes you will not be troubled by some

degree of execution of expression.

“There

should be total and natural free flow -- but inspiration does not come every

day, this happens just several times a year. But the point is to be ready so

that it isn’t wasted. When you are playing with someone and they get

the spirit it is infectious: the other musicians get it, the audience gets,

everybody gets it and this is consummation of music and it is magical in way.

“The

whole thing about inspiration is that it is very mysterious and we have no

control over it, it comes or it doesn’t come. It is up to

it, whether it decides to pay a visit at a particular moment.

“It

sounds very Biblical, doesn’t it? I don’t

want to sound Biblical, but music is truly the language of the spirit.”

And

understanding this language and how to use it can be complex, as is listening

when you are a musician.

“When

I listen to music as a musician I listen on several different levels at the

same time, or rather several aspects. One is just the enjoyment of the person’s

playing, and secondly you naturally analyse at the same time as enjoying. So

there are several different functions moving simultaneously.

“When

I’m listening to what’s

going on inside of me or I start playing -- in addition to the phrasing which

modifies according to the way you feel and is very indicative of your state of

consciousness, you could call it a more sensual/physical side -- there’s

the intellectual side where for example you think about what extent

harmonically you can bring in elements.

“Any

note can follow any note so the question is ‘which

note?’, and that is guided by your taste in harmonics and in a

way we do what is done in art as in music, it is the question of how do you

taste it? People taste it how you taste it when you play it.

“When

I am working, it is how to do you from A to B to C while reviewing how you perceive

and how you can reveal harmonic relationships.

“Harmony

is part of the way of Western way of music and I am a Western musician --

despite all my work with the Indian musicians, which I will continue until I

give up the ghost. But the harmonic side fascinates me more than the linear

way, ‘how you can reveal different harmonic extensions in a linear sense while

not losing the fundamental colour of the music?’. “

To

hear McLaughlin -- who studied under Ravi Shankar, worked alongside numerous

Indian musicians and had guitars built to play more effectively using Indian

microtones -- describe himself as a “Western musician” is something of a

surprise. Surely, given the flamenco influence in some of his work, “world

musician” might be more appropriate.

“That’s

sweet of you,” he laughs, “but I don’t even think of

myself in any terms, I am just a working musician.”

What

draws McLaughlin from jazz to Indian music and back again is the common ground

of improvisation in both spheres. This is challenge, the be both composer and

performer in an instant, but he also sees that is a necessary part of daily

life.

“I

think this is one of the great lessons of life: when we are spontaneous is when

we are most ourselves and the most honest, we are natural and don’t

have time for artifice to come in the way.

“In

improvisation we don’t have to time to think, just play.

That’s the greatest moment because I believe if you are thinking you are not

really playing, and if you are playing you are not really thinking. This is the

ideal place to be in music, where you play you just be.

“There

is a lot to do every day because I am not the same today as I was yesterday. In

that sense every day is new and a challenge, and because I’m

a little different from yesterday - which is very small but over six months it

can be quite substantial -- and the way you perceive music evolves and with

your evolution and the music reflects that.

“The

work is keeping up with what’s going on inside of

you, that’s what my work is. I hear what is going on in my own mind

and have to keep up with that.”

Not

that McLaughlin is any kind of ascetic. The self-confessed Francophile has

lived in Monaco for over 20 years and enjoys skiing in the nearby Alps, or

popping over the border to enjoy the delights of Italy. He also has a family

but is cautious about what how much expectation to put on children, especially

as he has seen pushy parents up-close.

“I

have two boys and neither are musicians although the younger one might get to

it. I’ve seen children ruined by parents’

ambitions, on a couple of occasions quite tragically. So I am not interested in

forcing music on anyone because I saw these children revolt against this kind

of pressure.

“Human

nature is what it is and parent have stars in their eyes if their children have

talent. They live their vision through their kids. I don’t

try to push it on mine.

“Music,

my wife and I, agree should be part of any child’s

education until say 17 or 18, not that they should be obliged to learn an

instrument, but to know music and have the possibility of being and of having

access to instruments. Just like you learn French or English or mathematics, I

think it should be part of any curriculum, it’s

vitally important to the individual.”

And

while placing personal emphasis on the importance of being in The Moment, he

also takes the long view of his life.

“I

am an extremely fortunate person, I think being a musician is a great privilege

for a human being. To be involved in such work is very conducive to interior

development and it’s a wonderful force for peace and

love, if I can quote those old hippie values.

“I’m

still an old hippie, very attached to my hippie values.

“But

when I arrived in New York in early 69 it was primarily to play with Tony Williams,

but within two days I was in the studio with Miles, and you couldn’t

get much luckier than that.

“And

touring now with Chick is very significant because it was exactly 40 years when

we met and played together on In A Silent Way. We were neighbours down

in the Chelsea area of New York and we’ve had some white

nights discussing philosophy. He is a very special human being and very special

musician.”

So

of “Johnny McLaughlin, electric guitarist, Railway Cuttings, Sunnyside,

Yorkshire” (as that business card of his youth read) through a spiritual and

musical quest which saw him creating fusion before there was the word for it,

and world music a couple of decades before Womad, it is fair to ask what

McLaughlin has learned in life.

“Hmmm.

I’ve learned that the great supreme and wonderful spirit

that holds the Universe in place, and myself, are basically two aspects of the

one thing. A good lesson, the only lesson, it’s

the only one we have to figure out.

“I

think we continually learn lessons, it depends on how you see lessons. I wouldn’t

want ‘lessons’ to be in any way

negative, I think they are stepping stones to where we go. It’s

like doubt, it is an extremely important element in life without which we’d

never be able to work our way through to any kind of lucidity.”

And

after all this, after the amps have been turned off and the house lights go off

forever?

“I

think it will be a nice vacation,” he laughs. “You don’t

have to work and you can take it easy for a few thousand years. We’re

all on Death Row it’s just a question of time.

“But

we get to a point where we have to take ‘the big sleep‘, as Raymond Chandler

put it.”

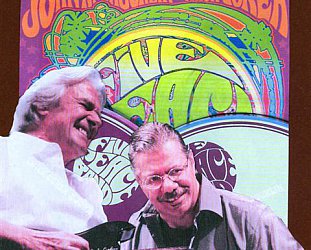

CHICK COREA AND JOHN McLAUGHLIN FIVE PEACE BAND REVIEW

Aotea Centre, Auckland, New Zealand, February 22, 2009

They

say never throw anything away, it’ll come back into fashion. Today, many might

be regretting getting rid of their mid-70s fusion albums after this exceptional

concert fronted by two of the mainsprings of that jazz-rock style, keyboard

player Chick Corea and guitarist John McLaughlin.

But

where 70s fusion too often disappeared up its own arpeggios, three decades on

these protagonists brought a wealth of subsequent experience to expand the

parameters while also reigning in the excesses.

This

was -- in places -- fusion, but not as we once endured it.

On

hand with these 67-year olds was a younger generation of players: saxophonist

Kenny Garrett, bassist Christian McBride (who came up through the

neo-conservative 80s but quickly abandoned its constraints) and the

extraordinary drummer Brian Blade.

When

there was fiery dialogue between these players, the enthusiastic audience

witnessed an intuitive, cross-generational conference call which scaled heights

and defied preconceptions.

From

Corea’s richly embellished piano ballad The Disguise full of abrupt

stops and directional changes (propelled by the muscular, musical and deft

playing of Blade) through McLaughlin’s staccato runs, keening notes and

breathtaking fluidity to Garrett’s astonishing, 10 minute flight of piercing

and screaming notes which conjured up the restless spirits of Albert Ayler and

Rahsaan Roland Kirk, this was jazz to be viscerally experienced.

The

assured McBride brought earthy five-string electric bass to McLaughlin’s New

Blues Old Bruise -- he and McLaughlin discreetly drawing the melodic pulse

back to suggestions of a Chicago blues riff -- during which Garrett made

references to North African music in his solo.

And

if Garrett could pull out a biting and astringent tone only to wittily drop in

the melody of Girl From Ipanema, Corea could equally shift from

attenuated lyricism to broad flourishes before handing over to McBride for some

melancholy arco playing on acoustic bass. Blade’s brilliance was everywhere,

and sometimes “out there“.

This

was music made by equals, much of which has been unequalled in this country.

From

new fusion to an overhaul of Jackie McLean post-bop swing on Dr Jackle,

from angular ballads to blues and galloping Latin rhythms, the Five Peace Band

brought lifetimes of experience into the present tense.

And

if at times it was a tense and intense concert -- that Garrett solo will

lingers for years -- then so be it: this was jazz without compromise, invention

without fear, and it was delivered by master craftsmen.

mark robinson - Feb 16, 2009

Excellent Graham. My phone conversation with John ran to only 20 minutes unfortuneatly (don't you hate it when those international voices come back on the line and say "you have 1 minute left").

SaveBut in those 20 minutes we covered off the menaing of life, drugs, the recent Mumbai attacks, our favorite beaches in India, Chic Corea, Miles Davis and crazy drivers in New Zealand (he was almost run over last time he was hear).

An amazing man and musician of course. If you'd like to hear my interview with John (edit down somewhat) with a music bed it is available here...nzjazznetwork.ning.com/

Alan Brown - Feb 23, 2009

Beautifully put Graham. An amazing experience, one that will stay with me for a LONG time... Lyricism, intensity, communication - such a privilege to behold.

SaveIncredible performances from Garrett & Blade, but really, everyone knew how to support and make everyone else sound good. True musicians, true musicality, true passion. Stunning.

post a comment