Graham Reid | | 3 min read

John Coltrane and Miles Davis: Two Bass Hit

For two people about to write themselves into music history, their credentials were not promising.

Only a few years previously, the trumpeter was so hooked on heroin that he was almost unemployable and would often fail to show for concerts.

The other was a little-known saxophonist whose career was sound but unspectacular. He had played in Dizzy Gillespie's small ensemble which had offered him his only significant solo opportunity on record, on a 1951 novelty song, We Love to Boogie.

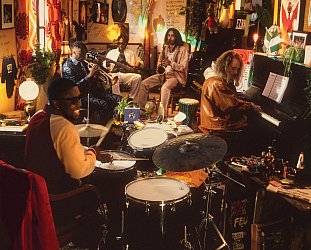

Yet when Miles Davis and John Coltrane came together in New York in the mid-50s, music history was about to be made. With like-minded players, they would enjoy a special chemistry and create - among other great music - the most popular and influential album in jazz history, Kind of Blue.

In the early 50s, after returning from Europe with the great saxophonist Charlie Parker, trumpeter Davis determined to go out on his own. But his unreliability and inability to find a suitable manager or agent meant work was sporadic.

When Parker decamped to California and began working with another young trumpeter - Chet Baker, who modelled himself on Davis - he decided to clean himself up by moving back to his parents' home in Illinois and going cold turkey.

Davis returned to New York in early 1954, started playing again, and approached George Avakian at Columbia Records to pick up his contract after his one with Prestige lapsed.

It was at the Newport Jazz festival in 1955 where Davis indicated in a superb set that he had returned and was playing better than ever. Avakian met him backstage and arranged for a meeting the following Tuesday.

Davis' audacious - and accepted - suggestion was that he record for both Prestige and Columbia, but Columbia would release his recording for them only after the Prestige contract ended.

Davis' band was capable of realising his new ideas. He still had the loyalty of pianist Red Garland, drummer Philly Joe Jones and bassist Paul Chambers. But saxophonist Sonny Rollins needed to clean up his own drug habit outside New York and had moved to Chicago. The replacement Davis had waiting, Cannonball Adderley, was a schoolteacher in Florida and his contract required him to return for work.

At Jones' suggestion he approached Coltrane.

Davis - at 29 and four months the saxophonist's senior - had rarely seen Coltrane play and, on the few occasions he had, was unimpressed. Yet, perhaps desperate as the recording date approached, he made the call. Coltrane joined Davis' band only a month before its Columbia recording debut on October 26, 1955.

It was an occasionally volatile relationship with Coltrane twice leaving and being replaced by Rollins. Yet the music made for Columbia by the Davis-led line-ups - Round About Midnight, Milestones and, in particular, Kind of Blue - defined an intellectual style of jazz others could only attempt to emulate.

For the following five years after those first sessions, Davis' band - which swelled to a sextet with Cannonball Adderley for Kind of Blue - was unassailable. The albums (for Prestige and Columbia) form a cornerstone in jazz.

Kind of Blue, released in August 1959, is still considered one of the most perfect amalgams of ensemble and solo playing, and its elegant, relaxed mysteriously profound modal style created a template for others to follow.

Davis' unique tone ("like walking on eggshells" became the most common description) is one which others attempt to replicate today.

The Columbia sessions of Davis and Coltrane have now been collected in their entirety on six CDs in a handsome metal box set which comes with essays by Kind of Blue drummer Jimmy Cobb, Avakian and others, and with detailed session notes and discography.

The Complete Columbia Recordings of Miles Davis and John Coltrane 1955-61 is perhaps one for collectors, but it is also an essential historic document. You can hear Davis' confidence and growth as an artist, the nascent genius of Coltrane given space to flourish, and the innovative ideas being interpreted with an intuitive and cerebral intensity.

The set also stands as a reminder of how important jazz once was.

At this distance, and in a world of manufactured pop stars where the marketing is more interesting than the music, it is difficult for us to comprehend the popularity and universal appeal of jazz up to the arrival of rock culture in the mid 60s.

Today we have Ricky Martin on the cover of Time magazine. Back then it was Duke Ellington and Dave Brubeck.

Jazz was not confined to the margins as it is now. It was a daring, innovative and exploratory music which carried an audience with it on its adventurous journey.

And in these extraordinary sessions, presented in this set complete with false starts and often equally penetrating and enjoyable alternate versions, you can hear the gears of jazz and contemporary music changing - very, very smoothly.

post a comment