Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Charles Mingus: Goodbye Pork Pie Hat

Stastics are easy to refute. Current research shows 87.5 per cent of all statistics are made up on the spot, right?

But some stats aren’t worth the trouble of arguing over. So let’s not dispute whether jazz commands about two per cent of its hometown market in the US (as Ken Burns said at the time of his insightful if controversial Jazz doco-series) or three per cent as Martin Arnold reckoned in an article in The New York Times around the same time.

Either way it was pretty negligible and below the margin of error. The question then is: if so few people are buying the music (and my suspicion is the figure, either figure, might have fallen since then), why would anyone want to publish jazz books? Surely there must be no market at all for them?

Yet the books still come. Burns wisely cashed-in on his tele-series with a thumping great and expensive volume, but on any given day in any good bookshop you can see new titles or reprints or shelves just waiting for an audience. And there is an audience surprisingly enough.

Publishers of jazz books tend to be university presses and specialist publishers such as Da Capo, which has a valuable back-catalogue it regularly reprints alongside new titles.

“Like military history fans,” says Andrea Schulz, senior editor at Da Capo, “jazz fans may be a small group, but they tend to buy every book written on the subject. They’re not casual fans but a passionate group of people.”

And they are being added to as new generations come through discovering some aspect of this century-old music. In that regard, Burns did jazz publishing a huge favour, he created a television series that was literary, and rich in characters and stories. Jazz readers tend to be educated and curious – but like a good story too.

Few writers have captured jazz artists as well as critic Gene Lee, whose Meet Me at Jim and Andy's is a series of profiles which are elevating and insightful, and in one tragic case, just mesmerizingly grim.

Trombonist Frank Rosolino was one of the best loved me in jazz, a joker who loved pranks, could keep the band in fits of laughter, and really play his instrument. So no one can fully explain what happened on the night of November 26 1978, when he went home, shot his two young sons then turned the gun on himself. One of the boys died, the other survived after 14 hours of surgery but was blinded.

Lees tells this story of a man he counted as a friend with unadorned clarity and lack of sentiment. It is a wonderful piece of writing but just one among many in Jim and Andy’s, which also include profiles of saxophonist Paul Desmond (of Dave Brubeck’s famous quartet), pianist Bill Evans, and band leaders Woody Herman, Duke Ellington and the much-married Artie Shaw. (Eight wives in all, which included glamorous women such as actresses Lana Turner and Ava Gardner.)

Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful invokes the spirit of jazz through a series of fictionalised portraits of such self-destructive characters like Art Pepper and Chet Baker, and eccentrics like Thelonious Monk. The sound of music, the rub of drugs and the atmosphere of clubs (and in Pepper’s case, a prison cell) are all evoked with an eye for detail and ear for the spirit which impelled these musicians.

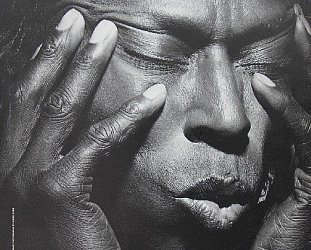

Some jazz players have taken to print – notably Miles Davis with his slightly revisionist and blunt autobiography dictated to Quincy Troupe – but few have achieved the notoriety of Charles Mingus, whose rude, crude and vibrant Beneath the Underdog is more about fucking than playing. Jazz might be an intellectual art form but, as Burns has reminded. “It was born in the bordellos, whorehouses and saloons and is designed to get the opposite sex into bed.”

Mingus writes about that last part, and it’s probably a more true reflection of a musician’s life in the 40s and 50s than academics might want to believe.

Jazz critics have claimed large pieces of the music’s history, mostly by being there, conducting the interviews and knowing the key players. Leonard Feather’s Ear Witness to an Era was first published in 1986 and is this godfather of critics’ reflections of a life listening to jazz and grappling with its changes. It’s full of historical detail and anecdote, but it’s dense and probably doesn’t exactly jump off the page for the newcomer.

Valerie Wilmer was also an earwitness to jazz, especially as it became overtly politicised in the 60s and 70s and left critics like Feather behind. She knew many of the main players in hard bop and free jazz scene and her 1977 book. As Serious As Your Life is a landmark in jazz writing which looked unflinchingly at the impact of radical black politics on jazz musicians.

It’s the best insight into the project of free jazz as it was happening.

And finally, for those just wanting some handy reference text and overview, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, by Richard Cook and Brian Norton, is the size of a brick but more than just record reviews. The authors treat the discs as a chance to offer a brief synopsis of the lives of the artists, the writing is critical and pointed, and the album assessments reliably accurate. If they like it, you can guarantee it has some merit. If they don’t, then don’t go there.

It’s one for newcomers and old hands alike, and an ideal guide into the often arcane world of jazz. But be warned, you could get to like this stuff.

And the next thing you know you’re a statistic.

mark robinson - Aug 12, 2009

>>>But be warned, you could get to like this stuff.

SaveCareful - we don't want Jazz to become popular and uncool.

This book is on my list, Miles book was an excellent insight. Art Pepper's Straight Life is still my favorite - a wonderful piece of work from his wife. And of course "Bird Lives" is a book that should be read once a decade. Mark

post a comment