Graham Reid | | 4 min read

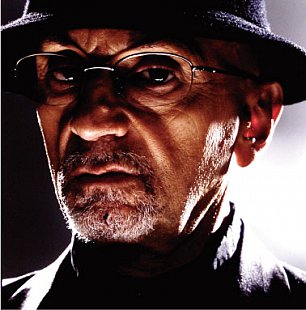

To hear trumpeter Tomasz Stańko tell it, life in Poland in the 1960s might not have been quite as grim and mono-chromatic as we believe. -Certainly there was the irony of playing free jazz in the politically repressive atmosphere, and he laughs knowingly when offered a quote by composer-pianist Thelonious Monk: “Jazz and freedom go hand in hand.”

“But you see in my time Poland was different from other countries in the Communist bloc,” he says. “Even in my diploma I was doing a jazz programme. Of course, in my younger time there was a different culture, very dark. Jazz was then forbidden.

“But in the 60s everything was a little more open. In the movies we had [director Roman] Polanski and there was [composer Krzysztof] Penderecki with Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. So Poland was different.”

Today, Stańko – whose formative musical moment was seeing American pianist Dave Brubeck in 1958, before being inspired by Ornette Coleman and making the great leap sideways into free jazz – is one of Europe’s most prominent and respected jazz musicians.

He has been signed to prestigious European label ECM for the past 15 years, and has worked in Europe with many American musicians, including avant-garde players such as Lester Bowie and free-jazz piano genius Cecil Taylor.

While grounded in the American tradition, there is a uniquely European quality to Stanko’s music today which can equally draw on contemporary classical traditions and traditional folk elements, as much as his trumpet playing being notably influenced by Miles Davis’s poised style of his Kind of Blue period 50 years ago.

That complex sensibility was evident on his Soul of Things album (2002) which, although almost the 20th in his long career, is considered by critics to be his breakthrough.

An emotionally deep and often intellectual meditation, Soul of Things -- unusually for ECM austere releases -- comes with liner notes which observe that one of the more introspective pieces refers to an old Polish melody which Stanko doubtless heard frequently when he lived in Kracow.

To attempt to draw him out on this often melancholy, occasionally vigorous, and always melodic album is to run into both a language barrier and an amusing, intellectual, evasiveness.

Apologetic for his imprecise English, he sidesteps any attempt to have him explain his musical motivation.

“But that is the world of a writer who wants to describe and put down words about this music,” he laughs. “A musician does not think like that, I cannot say in words something for you about the music”.

Which also explains why none of the pieces have titles other than Roman numerals, he didn’t want to have them to refer to something outside of themselves.

Stanko lives a somewhat austere life: he practices yoga, and is of modest means and desires. Acclaim in jazz doesn’t mean material wealth necessarily follows, and he recalls what he learned from being in Cecil Taylor‘s big band in the mid 80s.

“He was very . . . . poor, you might say . . but he taught me that music is an art, an expression. That is the most important lesson.”

Last year Stanko took a small apartment in New York, but his career has always been in Europe. He didn’t play in America for more than 20 years after 1984, but that distance from his original inspiration him allowed him to find a unique and personal language in jazz.

Stanko’s search for expression with other like-minded players in his youth meant he became part of a small group which would enthusiastically share treasured recordings by American jazz musicians.

“It was an adventure because it was hard to find records, but we were clever, we would always find a way. If someone was coming to Poland we would tell them what we wanted. And we would only get the best, of course.”

He recalls the shared sense of community and how it included composer/pianist Krzysztof Komeda who created soundtracks for many of Polanski’s films (among them Knife in the Water and Cul de Sac, and later Rosemary‘s Baby when he followed Polanski to the United States).

Komeda was among the prime movers in creating a distinct, sometimes academic, style of European jazz. Stanko joined Komeda’s quartet in 1963 and worked on a number of soundtracks with him, “but these were untypical” he says, to distinguish them from his jazz work.

In the Seventies he played with Ornette Coleman-alumnus Don Cherry and Penderecki, toured in Europe extensively -- first with drummer Edward Vesala (latterly an ECM mainstay also), then with pianist Adam Makowicz (who moved to the United States in the late Seventies) -- and increasingly with international players working in Europe.

His Matka Joanna album (1994) found him with British free jazz drummer Tony Oxley, and pianist Bobo Stenson and bassist Anders Jormin from Sweden. It was a typically difficult and sometimes dense affair, but in the past decade he has come to reconsider the nature of free jazz.

As with pianist Chick Corea who abandoned it because of its emotional failure to communicate with an audience, Stanko now considers free jazz “a way of thinking” rather than a musical result.

His analogy is distinctively European: that while free jazz offers many possibilities, as in politics “[possibilities] can also lead to Stalinism“, he laughs.

He also reflects on that freedom of expression he found in Coleman all those decades ago: ““But when people think of [Coleman] they always think that he is free jazz, but his music is very disciplined and composed.”

As he has moved from the muscular free jazz of his youth to a more measured, often introspective and lyrical style, Stanko has been widely hailed. In the early 90s he formed his current quartet of Polish musicians who were all in their teens when he first heard them: pianist Marcin Wasilewski, bassist Slawomir Kurkiewicz and drummer Michal Miskiewicz.

Unlike himself at that age, he says, these musicians knew the history of this music and were already confident despite their youth.

It is this quartet which comes to Wellington Jazz Festival, and which has been on Stanko’s most artistically and commercially successful albums.

Soul of Things won the inaugural European Jazz Prize -- the jury citation noting Stanko as “a charismatic performer and original composer, his music now assuming simplicity of form and mellowness that comes with years of work, exploration and experience“.

The quartet’s most recent album Lontano (2006) has enjoyed critical acclaim for its elegant sensitivity and deft ballads. He expresses what sounds like an uncharacteristic pride in it, and the album is emblematic of a man moving ahead but carrying his history with him.

The lyrical Kattorna is a piece by Komeda which he first played in his mentor’s group four decades ago and the lonesome Davis-influenced Tale is a reworking of an original composition from his 1974 album Balladyna. Yet there are also passages which find him in a more expansive and exploratory mood.

At 66, it seems Tomasz Stanko is still finding freedom within constraint, much as he did in his youth.

For more on Tomasz Stanko at Elsewhere go here.

post a comment