Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Introspection (1947, with bassist Gene Ramey, drummer Art Blakey)

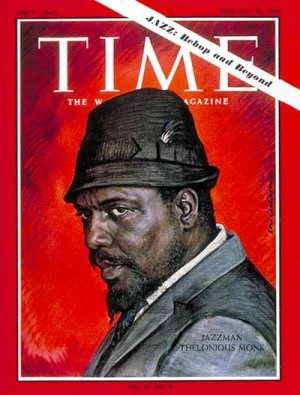

In late November 1963, a 5000 word profile of Thelonious Monk was scheduled to appear in Time magazine. Monk was to be the cover.

An interviewer and jazz aficionado Barry Farrell from Time had spent months with Monk watching him at work and relaxing at home with his family, and the Russian painter Boris Chaliapin had been commissioned to paint Monk's portrait. (Chaliapan complained that Monk repeatedly fell asleep).

But it was all in place and Monk was to receive, belatedly, a huge boost in profile.

Then a week before the story was due to run President John F Kennedy drove through Dallas in an open-top car.

In a way this kind of event beyond Monk's control was emblematic of so much of the composer/pianist's life: band members would suddenly quit, planes or cars wouldn't arrive to get him to a gig; record producers would lumber him with an inappropriate idea, there were two house fires . . . And a president shot.

To be fair -- and writer Kelley is scrupulously fair and balanced, his 14 years of research woven into a compelling story -- Monk was also his own worst enemy: he would be late to gigs, uncommunicative, wilful, reclusive, difficult . . .

But what emerges in this beautifully written and important book is that Monk was also not what so many thought of him as: he was not an untutored and instinctive genius of jazz piano (he had studied classical music as a child as much as the jazz tradition); he was not constantly grumpy but a loving family man with a devoted wife in Nellie and a supportive mother, brothers and sisters; he was not an eccentric staring off into space for hours but a man who suffered from undiagnosed bi-polar disorder.

Monk was many things to different people: a loyal friend to his fellow musicians who became junkies, an unreliable cuss to many concert promoters and nightclub owners.

Monk was many things to different people: a loyal friend to his fellow musicians who became junkies, an unreliable cuss to many concert promoters and nightclub owners.

Yet when that Time magazine story was finally published in February '64 -- the same month the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, a musical sea-change which would also adversely affect Monk and jazz in ways they couldn't foresee -- the writer repeated many of the same old cliches which had floated around for almost two decades.

Monk was portrayed, Kelley writes, as "a strange, reclusive genius, with an eccentric taste for hats, little connection to reality, a childlike demeanour, who depends on women to care for him". (Nellie and the loyal Baroness Nica de Koenigswarter, aka Nica.)

Kelley notes that the Time writer has Monk vehemently protesting the "mad genius" label -- but then goes on to recount incidents which had seen him confined to mental institutions. In one particularly damaging passage Kelley notes, Farrell wrote, "Every day is a brand new pharmaceutical event for Monk: alcohol, Dexedrine, sleeping potions, whatever is at hand, charge through his bloodstream in baffling combinations".

The article was charged by some as being libellous and revolting, not only unfair but untrue, and within radical black culture as yet another example of a white writer/establishment taking down one of its own, a man raised in the ghetto but who recalibrated the compass of jazz.

So who was the real Thelonious Sphere Monk? More than any other, Kelley's book tells you.

Kelley traces the family origins back to slavery days, follows the young Monk from North Carolina to New York City (when Thelonious was four his mother left the father and took her three children in search of a better life) and how the boy studied piano, came to whole new sounds and phrasing which he brought to his compositions, and yet was marginalised as much as he was acclaimed.

Kelley traces the family origins back to slavery days, follows the young Monk from North Carolina to New York City (when Thelonious was four his mother left the father and took her three children in search of a better life) and how the boy studied piano, came to whole new sounds and phrasing which he brought to his compositions, and yet was marginalised as much as he was acclaimed.

Kelley is there every step of the way with Monk, unflinchingly recording his triumphs and the many tragedies which befell him. He notes that Monk was "invented" in 1948 in "fewer than two hundred words".

This was the press release written by Lorraine Lion, wife of Alfred of Blue Note, when promoting his first recordings. Lorraine "established the lens through which the entire world would come to see Monk. Elusive, mysterious, strange, eccentric, weird, genius -- these were the foundation adjectives that formed the caricature of Monk".

It was Lorraine who also coined the much used phrase "the High Priest of Bop", presenting Monk to jazz audiences as a kind of mystic.

Monk was cornered before he even got a start. The media copyists took over from there and whenever Monk conformed to type it would be recorded.

Monk was cornered before he even got a start. The media copyists took over from there and whenever Monk conformed to type it would be recorded.

Fewer writers noted when he turned up on time (mostly he did), or was witty and communicative.

It was always about the unusual hats, the odd dances that he would do (a kind of conducting, a mannerism that Tom Waits would adopt), the drinking, being busted (he took the rap for another in one instance), the strangeness . . .

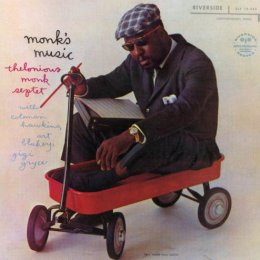

Sometimes the music he made -- powerful, dissonant, sublimely melodic, discordant yet oddly harmonious -- would get a mention. Kelley records all of this: the media coverage, the wildly varying record and concert reviews, the stereotyping and the insightful comments.

He also weaves in the changing times: how Monk's unique style bewildered many but was hailed as brilliant by others, and then how -- because he lost his cabaret licence and couldn't perform, or lost band members who couldn't play his complex music -- he became marginalised.

He also weaves in the changing times: how Monk's unique style bewildered many but was hailed as brilliant by others, and then how -- because he lost his cabaret licence and couldn't perform, or lost band members who couldn't play his complex music -- he became marginalised.

While Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were acclaimed as the founders of bebop, Monk -- clearly an inspiration for many and utterly distinctive in the genre -- received little acknowledgement.

And then the avant-garde, jazz-fusion and militant free jazz forms arrived in quick succession and suddenly Monk and his music were prematurely labelled as conservative, the old thing.

Monk's star constantly rose and fell and all that remained constant was his inability to make a living for most of his professional life, despite acclaim from many quarters.

Kelley pays close attention to the music (he is excellent in his potted analyses of Monk's recordings without ever losing the pace of the biography) and he usefully weaves in brief biographical accounts of Monk's fellow musicians where relevant.

Kelley pays close attention to the music (he is excellent in his potted analyses of Monk's recordings without ever losing the pace of the biography) and he usefully weaves in brief biographical accounts of Monk's fellow musicians where relevant.

He also locates Monk in the history of New York, its clubs and changing times when soldiers returned from the Second World War, its jazz scene and black politics, housing projects and multi-culturalism.

Monk was very much a victim of his circumstances, as much as he benefited from them. He was acclaimed by his peers, notably Duke Ellington (whom he admired), could play stride style like those who went 30 years before him but was always contemporary -- at least right up until those tragic years at the end where he retreated to Nica's home, seldom touched a piano and often just lay on his bed fully clothed, for day after day, month after month, year into year.

"If his health improved and his manic-depressive cycles were under control, why did he stop playing?" Kelley asks, then notes that after studying his life he wasn't surprised by Monk's decision, wondering why he didn't retire earlier.

"Consider the final years of his working career: his record label had dropped him, he could barely sustain a working band, his money was inadequate, he was practically reduced to opening for rock and r'n'b bands, he endured unremitting criticism for playing the same music, he lost all inspiration to compose, the lithium treatments deadened his senses and slowed his creative drive, and his on-going battle with incontinence made performing an ordeal. And his old friends kept dying . . . So why should he feel like playing?"

Monk was found unconscious in his room at Nica's in February 1982. He had suffered a stroke complicated by a bout of hepatitis. He was taken to hospital and lay in a coma for 12 days. He died on February 17 in Nellie's arms. He was 64.

Eccentric and strange Monk might have seemed, and yes he did have a taste for unusual hats (to cover his increasing baldness as much as anything else). But equally he redefined jazz piano and composition, and his cornerstone work -- much of it composed in his early career -- are jazz standards.

In 2006 Thelonious Monk was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his contribution to jazz. It might equally have been simply for his contribution to music -- and this remarkable, thoroughly readable biography will tell you why.

mark robinson - Mar 2, 2010

Yes I have mine on order - i don't need to add anything else about Monk.

SaveBy the way I just finished an interesting and informative bio on Ronnie Scott - "Jazz Man" by Brian Fordham.

post a comment