Graham Reid | | 17 min read

Al Di Mela: Race With Devil on Spanish Highway

At 55, Al Di Meola -- who still lives in New Jersey close to his musical roots -- has had a long and influential career, and was one of the great innovators on electric guitar.

In the late Sixties and early Seventies he played small clubs in New York and around Boston while at Berklee, but was largely an unknown when he made his debut appearance with the jazz-fusion outfit Return To Forever at Carnegie Hall alongside keyboard player Chick Corea and bassist Stanley Clarke. The following night he played with them before 40,000 in Atlanta.

It was 1974, he was 19 and he’d started at the top.

Di Meola not only brought jazz and rock to the band but a longtime love of Latin music which he assimilated into his sound. Santana -- who he admired and with whom would later play -- had been down this path, but Di Meola came from a different and distinctive direction.

“I used to hang out by myself as a teenager in these Latin clubs because I was just completely entranced by the sound of the Latin big bands and it had an amazing effect on me as a rhythm player.”

That lifelong love of Latin music -- after some exceptional electric albums post-Return To Forever (which he quit in ’76) in the Seventies and acoustic concerts with fellow guitarists John McLaughlin and Paco de Lucia which lead to the multi-million selling Friday Night in San Francisco album of 80 -- lead to the formation of World Sinfonia.

That lifelong love of Latin music -- after some exceptional electric albums post-Return To Forever (which he quit in ’76) in the Seventies and acoustic concerts with fellow guitarists John McLaughlin and Paco de Lucia which lead to the multi-million selling Friday Night in San Francisco album of 80 -- lead to the formation of World Sinfonia.

This is Di Meola’s multi-cultural ensemble which he considers the most rewarding musical experience of a career which has included playing alongside Paul Simon, Stevie Winwood, Pavarotti and Jimmy Page as well as everyone who is anyone in jazz.

In advance of another World Sinfonia tour in 2010 Di Meola, spoke from his second home in Miami . . .

Yes, you catch me at my home in Miami. I have a place here I come to do some writing.

Is it also time off, a place where the balmy climate invites you to put your feet up and have a beer?

A bit of both, but mostly writing for a new recording.

But you are still a New Jersey boy, you still have a home there?

Oh yeah, for sure. I almost moved down here completely, but at the last moment I couldn’t separate myself from the proximity to New York and my roots and so on. So I maintain that and I have offices and a studio there, but then I have this place on the beach in Miami so I get the best of both worlds.

It’s totally transformed from what it was 20 years ago, now it’s a very happening place with a lot of great restaurants. It’s amazing. I got this place here 15 years ago, it was very different then.

You are in writing mode at the moment, is that for World Sinfonia or a commission or something else?

It’s World Sinfonia, for sure. We’ve been touring a lot, there are a couple of live records and now finally a studio album we can do.

But you also went out with Return To Forever in 2008, do you block out time for that in advance.

Yes, that was a big project so I stepped out of my normal group to do it.

Let me ask you about that. Is that one of those occasions where you step up with those people and the magic all comes back, or do you really have to rethink it having been so long away from it.

Would you believe that it just came back, and I didn’t realise until now, 30 years later, how easy that music was comparative to what we do with World Sinfonia.

Because I was in that group when I was a teenager, and my recollection was of that period and the challenge and that it was very difficult. So coming back it was really easy, it was fun and nostalgic more than anything.

I spoke to Branford Marsalis recently and he said that when he looked back to the music he was playing when he was touring with Sting that you didn’t have to rehearse it was so easy. I guess that is the thing with jazz musicians, your threshold of playing is so much higher than people who play rock music.

Luckily I have the ability to go between a few of those worlds, I come from a fusion background because I started with jazz, and grew up with the rock and pop era, but I absorbed a lot of Latin music and so it all came together.

But what’s nice is that after all the years playing electric guitar I am very well accepted by my audience and accepted to do acoustic music even though I had an early stamp as an electric player.

I was fortunate to be involved with the acoustic guitar trio [with John McLaughlin and Paco de Lucia] as far back as 1980 and that planted the seed that has enabled me to do all the things acoustically without an audience feeling like they have to hear me on electric.

Back to Return To Forever, briefly. John McLaughlin and Chick Corea came to New Zealand with the Five Peace Band and there was a huge response. It struck me that fusion had come back, not just for the old audience but for a young one. I suspect the younger audience finds it an exciting music. Did you notice a new audience when you went out with Return To Forever in 2008?

Pretty much, there were a lot of our fans bringing their kids. But it was also an event us getting back together and we’d all become well known in our right. So for us to reunite, in the minds of a lot of people they were viewing it as a one-time last chance.

It became an event and became the biggest jazz event -- forever possibly.

It was shorter lived than it should have been, even the first time around. But then you are dealing with very complex individuals.

Where everyone has their own interests.

[Laughs] They have their own religions even. I could elaborate to make this the most interesting interview on the planet but I’d get into trouble.

I know, I interviewed Chick in 2007 and asked him about Scientology and I have to say he was very happy to talk about it. He seemed like a better person to have fronting it than Tom Cruise, but then I don‘t have to share a stage with him.

I know, I interviewed Chick in 2007 and asked him about Scientology and I have to say he was very happy to talk about it. He seemed like a better person to have fronting it than Tom Cruise, but then I don‘t have to share a stage with him.

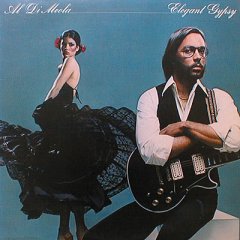

Back to your music though, I know your music from Elegant Gypsy days ['77] and picked up on that, and then went back to Return To Forever. But you spent a long time away from electric guitar and I understand tinnitus was the problem, but was that the sole reason you moved away from electric guitar?

It was more than 50 percent the reason. For sure. The amount of hearing damage that all musicians have is more than you could imagine. Some of us have a loss but others might have an affliction like a constant ringing than never goes away, ever. And that’s tinnitus.

It can only get worse and can never get better and it is a scary thing to have to endure constantly. The times you are more aware of it is when there is absolutely no noise around you to distract you, and it has become a bit of an issue. There are things you can do to keep it from getting worse and that’s what I have done.

I still have the urge to play electric and do now and then, but the appeal of a drummer playing at full volume and big giant amplifiers? Just the thought of it makes me cringe. It’s not only a thing of danger, it just doesn’t appeal to me very much.

I remember you told Downbeat magazine in 1983 there was time you wanted to become the fastest guitarist in the world, like track stars, but even by ‘83 that was over for. So you moved to acoustic. That would seem to be a much better instrument to pay the Latin-influenced music that you were exploring?

Yes, because I am primarily a rhythm-oriented player and my leanings are towards playing rhythm a lot, and that is better suited on acoustic.

The electric guitar is primarily a lyrical instrument and so I try accomplish both on the acoustic in the setting, because of the complexity of the music the acoustic lends itself better.

This is the style of the [World Sinfonia] group as it stands, a mix of influences in an acoustic setting. That doesn’t mean I don’t throw in an electric piece from time to time.

You were a longtime fan of [Argentinean bandoneon] Astor Piazzolla’s music and a personal friend. What was it in his music that appealed to you as a guitarist?

You were a longtime fan of [Argentinean bandoneon] Astor Piazzolla’s music and a personal friend. What was it in his music that appealed to you as a guitarist?

It just sits so well on guitar, when you read the music it is so perfectly written for it. What was unique about it was that not many guitarists had done anything with Piazzolla other than some classical guitarists.

But no one in jazz had touched on it, so it became a unique situation where I was like the first guy to do something in an original way with his work -- which, by the way, he encouraged me to do.

He was very encouraging and a big fan of my music. In fact he was a fan of mine before I even knew of his music, so I had a curiosity and desire to learn more of what he was about . . . because I liked him first as a person, and then when I found about the music it hit me like a thunderbolt, just the strongest sensation overcame me because this was a music that transcended anything that fusion was about.

Whereas a lot of the fusion was purely technical and cerebral and dazzling maybe, his music had an equal amount of complexity and technical challenges -- but it was touching my heart and moving me emotionally, and that had far more depth and meaning than a lot of the fusion music that you heard from a lot of the artists doing it.

So the direction of this influence really played a part in my further development as an artist and I’m grateful for it -- and World Sinfonia is the vehicle for all of that.

Because it is, for want of a better phrase, a multi-cultural group where people are bring influences from their own backgrounds?

Definitely. With Fausto [Beccalossi] on accordion -- who is one of the greatest instrumentalists in jazz today on his instrument -- playing together I have the deepest collaboration I have ever had with a musician where there is no ego involved. We have a conversation together and that is very rare.

I’ve played with some of the greatest players on the planet, but the thing we do together fits like a glove.

I know some of the names of people you have played with so that is an enormous compliment to him -- but also a fortunate thing to find in your life, someone you can work with?

It is amazing, it’s like finding the perfect soul mate. He plays on a very high level when he improvises but when we play together there is no ego problem,. When he goes left I go left, it is amazing how we completely complement that and there’s no weird vibe from it.

With a lot of star musicians -- and I won’t name names --- if you do something interesting but wasn’t exactly what they were thinking you can get a weird vibe from them. It’s not something an audience might pick up on, but it happens with some of the best players.

With Fausto and I, we have a freedom, and the depth at which we take it is so rare. It is definitely the deepest thing I’ve ever done. And I’ve had some great moments with Paco and Chick, but this is something different.

This is exactly where I wanted to go with Chick in Return To Forever originally, but egos over time grew so huge -- so it was hard to get intimacy with guys who are so rigid.

When you play with other people, presumably you learn a little bit of something more every time. If I can go way back, when you played with [bassist] Jaco Pastorius, what did you hear from him?

We’d never heard anybody play a fretless bass to that kind of degree. It had just never happened before and -- it’s like how someone plays lines and the intellect and fluidity and the technical aspects -- when it all comes together, and the sound being great . . . the world had never heard anything like that.

We’d never heard anybody play a fretless bass to that kind of degree. It had just never happened before and -- it’s like how someone plays lines and the intellect and fluidity and the technical aspects -- when it all comes together, and the sound being great . . . the world had never heard anything like that.

I’m fortunate to be able to say that he played on my first solo album and that was the first time he was ever in a recording session.

You say that we had never heard that before, but we also don’t hear much of that style of playing today. I don’t hear anybody as good.

There are a few guys who are, but immediately they are considered a Jaco rip-off. Immediately, because it is so identifiable to Jaco and that was exactly his bag.

And if anybody comes close they are going to be dubbed “he’s a player who plays like Jaco”. So the guys are shying away from it, and they are realising they can never be as good as that.

There was something about Jaco, his feel and sound, he was the greatest.

What about Carlos Santana, a man who works a lot with Latin rhythms in his music, but his guitar playing? When you work with him what did you hear which made you think ‘that’s something I hadn’t thought of’?

Carlos always had a tone that everyone strived for, actually everyone dreamed of because striving didn’t mean we ever got it. People dreamed of that tone, it was wonderful. He was a guy I listened to in high school and that I admired so much because I loved the whole Latin element and the drive of their rock thing with the Latin percussion.

So he was definitely spearheading a group which had this influence on me growing up and my times playing with him were quite wonderful and something I treasure.

Off on a tangent, you just did the one session with Paul Simon [for the Hearts and Bones album in ’83]. Why did you do that?

I grew up with Simon and Garfunkel and was a tremendous fan, not a little fan. He asked me to play on that record the first time Return To Forever did a reunion and it was right at the time Eddie Van Halen did Beat It with Michael Jackson and I knew he was thinking, ‘Who can I get who is going to have an impact like Jackson did with Beat It?’

I was honoured to do it, it was so great.

You speak like a fan which is lovely to hear, so many musicians are well past that. When you were growing up was there a lot of the Latin-influenced music in your home?

Not at home but I grew up outside New York City and I used to hang out by myself as a teenager in these Latin clubs because I was just completely entranced by the sound of the Latin big bands. It had an amazing effect on me as a rhythm player -- and I think I’m a far better percussionist than I am a guitar player, but that’s a whole other story.

You started off as a drummer?

Well I started off with drums, but I wouldn’t say I was a drummer because I don’t have great footwork. But I have good hand work and am a far better percussionist. That’s something I get involved with when recording and I’m very clear what I want, percussion-wise, on my records.

When I write it’s coming from a percussionist’s rhythm point of view. My music is always rhythm-oriented and my guitar playing as a result is very much based on syncopation.

There is so much syncopation in the arpeggiated underpinnings of my compositions that really sets it apart from guys like Santana who I view as more vocal-like guitar player and not so rhythmic. His band is rhythmic but he’s not.

But you have found for yourself this almost perfect vehicle in World Sinfonia which satisfies almost all of the things you want to do in music.

It does, because it touches on all the aspects of the influences I have and allows me to play to my strength which is playing rhythmically. And then also it can convey music which goes deep with emotion where it’s not just a cerebral concert of jazz.

Concerts I’ve gone to which are like that, my heart doesn’t get moved. I think the highest compliment is when people can feel a sensation, even if it is melancholy, it’s something which makes them go deep.

And that for me says way more than fusion of the past.

We all know that a lot of fusion was just speed for its own sake. I’d make a distinction though because particularly the album I got, Elegant Gypsy, I thought that was an extraordinary record which -- with all due respect to John McLaughlin and what he was doing with Mahavishnu Orchestra -- that was just flat tack. But pieces like Race With Devil on Spanish Highway was more than just speed, it was very considered and structured music, yet it was fusion.

We all know that a lot of fusion was just speed for its own sake. I’d make a distinction though because particularly the album I got, Elegant Gypsy, I thought that was an extraordinary record which -- with all due respect to John McLaughlin and what he was doing with Mahavishnu Orchestra -- that was just flat tack. But pieces like Race With Devil on Spanish Highway was more than just speed, it was very considered and structured music, yet it was fusion.

What made it unique was me coming from a strict rock-jazz fusion band, and John was doing his thing with rock meets jazz -- but no one had taken that Latin element and infused it into those other elements of rock and jazz.

When I did that it tied together that weren’t there before.

The electric guitar I can only see as a beautiful sounding instrument, not this thing with an overdramatic and mad sound -- but as an instrument which can express beauty. And what better way to use it than with Latin elements which can be romantic at times but also exciting at others?

So that was something I touched on and hopefully developed -- but then the intensity of music and complexity of loudness and big amps became much less appealing. Deeper music became more appealing and that leant itself to acoustic guitar than electric.

And by the way in Europe, where the bulk of my touring is, they are far more into acoustic than electric. My group has a far bigger audience in Europe than I witnessed with Return To Forever when we did our reunion. It was amazing how more receptive they are to World Sinfonia.

Just a totally different tradition perhaps?

Just a totally different tradition perhaps?

Yes, some tradition and some of what people have grown up with. Music that pinned you against the wall might not be what people want.

One last question. In all those years you weren’t playing electric guitar on stage, were you at home still playing or did you really shut it out completely?

I put it aside, but when I get into it I experiment with it more. So I go through periods where I don’t really play it. The acoustic has a more advantageous role in the ease of picking it up.

The electric guitar always signifies, ‘I gotta turn an amp on’ and an amp is always scary to me. How many years can one endure the volume from an amplifier before you just lose it?

So I’m very careful -- and it doesn’t hold the same appeal in its loudness.

In concert I’ll pay it on maybe two or three pieces, but I won’t have the amp facing me, that’s for sure.

post a comment