Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Archie Shepp: Attica Blues

Few

people today -- musicians included -- consider rock or jazz as

“political”, even in the broadest sense of the word.

Yet

back in the late 60s and through the 70s large areas of both

certainly were. Less than a year after that remarkable year 1968

(student demonstrations, assassinations, political oppression and

revolutionary activity) the dialogue changed.

Jefferson

Airplane who urged you to “feed your head” now shouted “up

against the wall, motherfucker”, and John Lennon was

ambiguous/ambivalent about revolution: “Don’t you know you can

count me out/in”.

Jimi

Hendrix, whose exploratory music increasingly stood between

improv.rock and free form jazz was being hauled into Black Panther

debates because he was black but his audience was predominantly

white.

By

1970 Miles Davis was increasingly looking to connect back with a

black audience (the Jack Johnson album, then the street funk

of On the Corner), and even further out were jazz groups like

the Revolutionary Ensemble and the Art Ensemble of Chicago,

saxophonist/writer Archie Shepp (“let my notes be bullets”) plus

jazz-inspired performers like Amiri Baraka, The Last Poets and Gil

Scott-Heron.

In

much 70s black jazz, revolutionary political thinking was no subtext:

it was in your face in music with titles such as The African Look,

Attica Blues (after the prison massacre in California), Chicago

(after the riots), The People’s Republic, For the People and so on.

In

much 70s black jazz, revolutionary political thinking was no subtext:

it was in your face in music with titles such as The African Look,

Attica Blues (after the prison massacre in California), Chicago

(after the riots), The People’s Republic, For the People and so on.

Jazz

was freedom music (of expression, if nothing else) and so musicians

liberated themselves from the shackles of form and free jazz became a

profound and prevalent mode of expression (although it had been

around since Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz album of ‘60).

Many musicians also liberated themselves from the legacy of white

America slavery and adopted African or Muslim names.

These

were exciting, angry and conflicted times -- were the Weathermen and

Panthers freedom fighters or terrorists? -- and the jazz reflected

it.

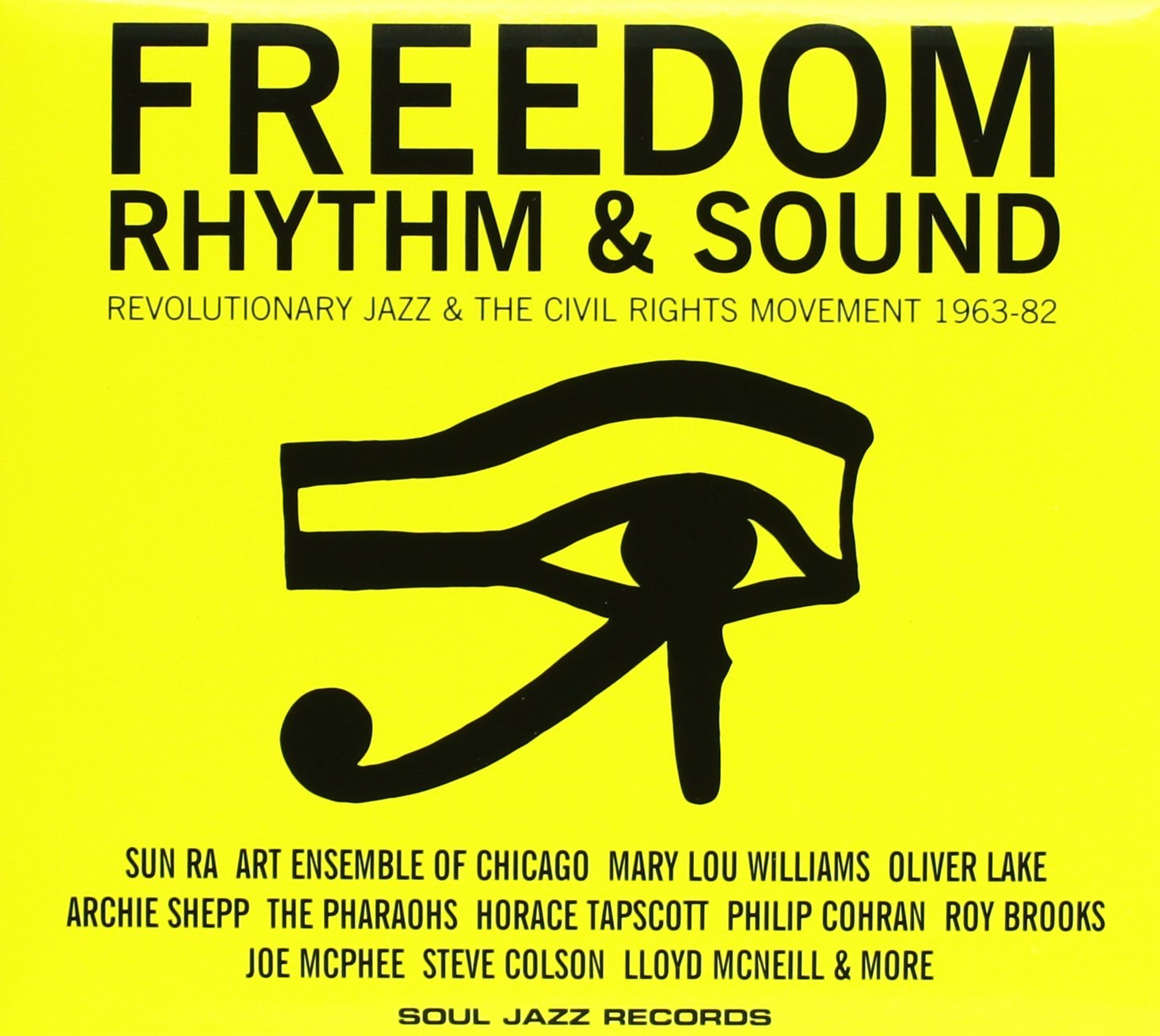

In

the absence of CD releases of many albums from that period -- most

were on small labels out of New York or Europe -- a two CD set

Freedom Rhythm and Sound (Soul Jazz) helps fill in this

important, and often forgotten, period in jazz.

Subtitled

“Revolutionary Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement 1963-82”, these

discs cut a wide path through jazz and improvised music and include

big names (Sun Ra with his seminal, seven minute Nuclear War, the Art

Ensemble of Chicago, Oliver Lake, Archie Shepp with the raging Attica

Blues, Horace Tapscott) alongside the likes of Errol Parker, pianist

Amina Claudine Myers (too often relegated to a footnote despite being

a member of the AACM and work with Shepp and others) and many more.

Subtitled

“Revolutionary Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement 1963-82”, these

discs cut a wide path through jazz and improvised music and include

big names (Sun Ra with his seminal, seven minute Nuclear War, the Art

Ensemble of Chicago, Oliver Lake, Archie Shepp with the raging Attica

Blues, Horace Tapscott) alongside the likes of Errol Parker, pianist

Amina Claudine Myers (too often relegated to a footnote despite being

a member of the AACM and work with Shepp and others) and many more.

Just

as Gil Scott-Heron would warn the complacent black middle class that

“the revolution will not be televised”, so here Gary Bartz NTU

Troop says “never will be a revolution while you’re drinkin’

wine” in the woozy, Afrojazz-framed Drinking Song. It was time to

get straight and “say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud”.

Eyes

and ears here are on Africa (Oliver Lake with NTU on Africa, Arkestra

trumpeter Philip Cohran and the Artistic Heritage Ensemble on The

African Look) and to more recent music out of New Orleans and slavery

days. Black music from the past to the future.

Coinciding

with a Gilles Peterson and Stuart Baker book of album cover art of

the same name (equally DIY and fiercely independent) -- and including

a booklet of period photos -- Freedom Rhythm and Sound

collects consciousness raising and politicised jazz which is

thrilling and courageous in its anger, soul-funk, assertion and

exploratory nature.

post a comment