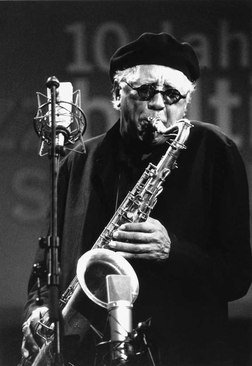

Graham Reid | | 8 min read

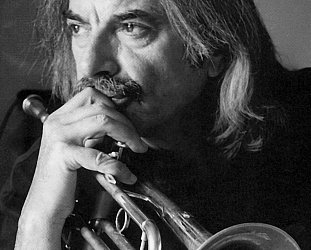

Charles Lloyd, Zakir Hussain, Eric Harland: Little Peacerom Lift Every Voice, 2002)

For

exceptional people, we make an exception. And saxophonist Charles

Lloyd is certainly exceptional.

Not just

because he enjoyed that rarity in jazz, a hit album (Forest

Flower in 66 which

anticipated the free spirit of the hippie era), or because he played

bills with Jimi Hendrix and Jefferson Airplane.

And not

because he moved in literary circles with Beat writers Jack Kerouac and poet

Lawrence Ferlinghetti; or that his fusion music pointed a direction

Miles Davis would follow.

All these

things are outstanding, but we make the exception because Lloyd –

now 72 -- is still making remarkable and innovative music, the past

two decades being the most fruitful and rewarding for him and his

audience.

So for

him we break the long-standing practice of declining an interview by

e-mail. But Lloyd suffers from a throat condition which means he has

to severely limit how much he speaks. But his courteous, thorough

answers to a series of written questions are more than adequate.

Charles, I am aware of your

early career but your most successful album Forest Flower came in a

rare and unique period where the lines between jazz and rock (in

popular culture) were rapidly falling away. The album was

commercially successful but I recall there was some critical

backlash. Jazz writers, it seems to me, have never embraced an artist

being commercially successful (they often think there has been some

compromise of artistic integrity) Were you hurt by some of the

criticism you received at the time? It seemed to deny the long

experience you had gathered before Monterey.

Looking back, the criticism came from a multitude of directions - but there seemed to be a consensus, at the time, that if I was experiencing such a degree of success, something must be wrong with the artistic expression. Success was equated with commercialism and not artistic expression. Today, everyone is trying to figure out a formula of how to achieve similar levels of commercial success.

The fact of the matter is, we were not calculating our moves with that kind of goal in mind, of becoming successful in the monetary sense. We were interested in the art with a capital A. But the music we were making connected with the youth at that time, and also with both the rock and classical world.

But success came at a cost and you had to retreat.

I don't know why that happened. I

had such a degree of success at a young age - excess came with that,

there was a price to pay for me musically and spiritually. My life was disintegrating , at

least I had the where with all to get off the bus to work

on myself. My naive notion was to make the world a better place

through the beauty of music - when, in fact, I

needed to change myself.

I don't know why that happened. I

had such a degree of success at a young age - excess came with that,

there was a price to pay for me musically and spiritually. My life was disintegrating , at

least I had the where with all to get off the bus to work

on myself. My naive notion was to make the world a better place

through the beauty of music - when, in fact, I

needed to change myself.

Those

were heady days when jazz artists would share the same stage as

psychedelic rock bands. Did you feel at the time that the world was

full of new musical possibilities in a way you hadn't seen

previously?

It felt like the sky was the limit. The lines of demarcation between genres were blurred, the audiences were open to all kinds of music, and we were exploring new terrain every night.

You went to the Soviet Union in '67. That was a time when it was a fairly closed state and frowned on jazz. I'm curious as to how your music was received there. Were audiences familiar with the larger history of jazz and your place within it?

Somehow they were able to pick up radio broadcasts from Finland. Our visit to the USSR was not sponsored by the government - that was a first. There had been visits by other jazz musicians at earlier periods, but always through a government program. I was invited by a group of writers, musicians, and scientists who had formed a music appreciation group. They invited us and the KGB made it very difficult for us to perform.

But finally we were able to play for the people and it was like an explosion had taken place. Years later, when I would run into people who had fled the Soviet Union to other counties in Europe, they would tell me that after I had been there, the saxophone had been banned. I always thought this was amusing folklore.

But when I was invited to return to Tallinn in 1997, I was given the keys to the city and some of the same people who had been there in 1967 came to greet me. I was brought to tears to meet Mr. Schultz, a physicist again. He had been sent to prison for his involvement in bringing me to Tallinn.

And yes, it had been true that the saxophone had been banned for 30 years.

(Editor's note: in fact the saxophone had been banned in the Soviet Union from around 1950)

You appeared to retreat from the high profile you had -- and yet toured and recorded with the Beach Boys in the Seventies while still playing jazz. What drew you to their music?

Brian Wilson wrote some incredibly beautiful music with very complex and sophisticated harmonies, that's reason #1. #2 - Mike Love and I were both born on March 15 and had a Piscean friendship and connection.

I shall skip ahead now. Your career on ECM has been little short of remarkable, a series of albums which -- for my money -- are among the finest in jazz of the past few decades. ECM has always had a reputation for a pristine style of recording. How did that come about: did Manfred approach you, or your management approached them?

In the late 1980s when I had decided to return to public life, my manager was Stephen Cloud. We had been friends for many years in California, and he had presented the concerts I made with Michel Petrucciani in 1981. Steve was also managing Keith Jarrett and knew [ECM founder/producer] Manfred Eicher. Manfred was interested in recording with me.

I had heard a few ECM recordings and knew them to be pristine, but somewhat cold. So, being from the warm climes of the South and Manfred being from the cool North - I was a little skeptical of the situation. However, Steve persisted and during that first session on Olso in 1989 with Bobo Stenson, Palle Danielson, and Jon Christensen.

After we had laid about five tracks Manfred said, "Do you want to take a listen?"

I was bowled over by the clarity of sound, and it felt like he had captured my warmth, too. That was Fish Out of Water.

What was it about ECM that appealed to you particularly? Manfred has a reputation for putting artists from diverse backgrounds together as a matter of course, I am guessing that might have been an attraction?

I like simplicity and quality.

You have been as exploratory in

your music on ECM as you ever were. Sangam is exceptional. You have

always had an interest in music of Asia. How did that project happen?

In college I was listening Bartok, Ustad Allah Rakha, and Ravi Shankar, along with shakuhachi and koto from Japan. When Gabor and I played together I opened him to Ravi Shankar and the idea of bending notes.

Time is short and there never seems to be enough of it to explore all of the ideas one has. But I am overjoyed that Zakir [Hussain] and Eric Harland and I found each other in this lifetime. Sangam means the confluence of three rivers.

I look at us as the Ganges, the Rio Grande and the Mississippi.

When we released Which Way Is East I wanted to make a special tribute Master Billy Higgins. Zakir and I had performed as a duo at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco in 2001, and by 2004 Eric was the drummer in my quartet. But rather than trying to recreate the same duo that Billy and I had -- this could never be done -- I thought I should play with the two drummers that Billy had sent to me from the other shore, Zakir and Eric.

It is an inspiring tapestry for me to fly on.

Lift Every Voice really was

healing music. You were in New York when 9/11 happened. Looking back

on that time, aside from your originals, how did you go about

choosing music for that album? What drew you to Blood Count and Deep

River for example. Did you conceive it as a long suite of music?

We were in NYC to open at the Blue Note on 9/11. I was staying a few blocks from the World Trade Centre and saw the second plane hit. It was a devastating time for all of us. I can still feel the pain of it today. After completing the tour I was on I went into hibernation mode, reading, meditating, and thinking about music.

Blood Count has such a haunting melody. It was the last song Billy Strayhorn composed from the hospital bed.

Finally, I decided I should go into the studio and get it off my chest.

So - yes -all of the titles combine to make a suite of messages. Wake up - the hour is getting late. War is not the answer only love can conquer hate.

You have played with some

exceptional pianists. I know this is hard but when these names are

put in front of you, what is the first thing that comes to mind about

their style and what they gave you as a musician, because I would

guess each brings something different? . . . Keith Jarrett. Michel Petrucciani. Geri Allen. Brad Mehldau.

My first mentor was a pianist, Phineas Newborn. He was our J. S. Bach, and he was an under appreciated genius. Without his help, I would not be who I am today. As to Keith, Michel and Brad -- and Bobo Stenson -- they are lyrical players, romantics coming out of Bill Evans. Geri Allen is perhaps more angular, and follows closely in the tradition of Herbie Hancock.

And finally: Jason Moran? What does he bring? And more generally: this touring quartet. In the long arc of your life tell me how you hear their place within it.

I'm always looking for that arrow into infinity. Jason comes out of Andrew Hill and Monk. He has developed an independent and soulful path of his own - and our work together gets deeper and deeper.

We have a very deep simpatico, and he understands the mission of service... as do Reuben and Eric. I feel this group is the "one." We have love and trust on and off the bandstand. They are fearless explorers. You have to be when you go out on a high wire every night, and there is no safety net. So, although the groups or context may change the intense focus and intent does not change.

In the arc of my life, this one is on the crest of the wave.

Sylvie - May 10, 2010

Having had the great privilege and pleasure to hear the Charles Lloyd Quartet last night, I remain more than a little blown away by the experience and have taken the opportunity to re-read the interview.

SaveWhat amazed me most perhaps - and it's well captured in the interview - was the sheer metaphysical dimension of the music that seemed to somehow envelop me ... along with possibly everybody else in the audience. Describing the event as an outstanding musical experience would be a tremendous understatement. (And no, I wasn't on drugs)

It really was something else

mark - May 24, 2010

Great concert - low attendence. where was the jazz crowd???

SaveI wonder if the promotors will be willing to risk another major jazz artist again?

Chris - Jun 28, 2010

Gutted i missed this due to being overseas at the time. Not a huge Lloyd fan but it would've been great to see Jason Moran live.

Savepost a comment