Graham Reid | | 15 min read

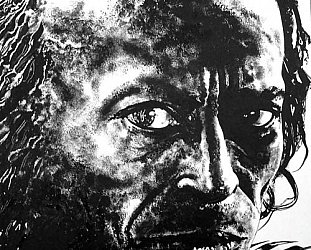

Joe Henderson: Lotus Blossom (from Lush Life, 1992)

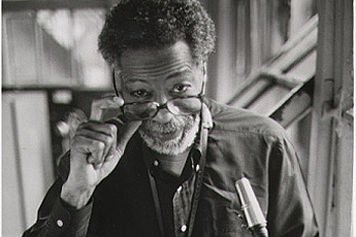

Joe Henderson is sitting at a press conference in Carnegie Hall,

New York, patiently answering another dumb leading question. Someone

among the contingent of journalists has just asked this legendary

tenor saxophonist -- who turned 57 this week -- why it has taken so

long for him to be recognised.

Henderson smiles wanly and with the humility that has been his

hallmark says maybe it was best he didn’t get acknowledged up until

recently - perhaps God thought, “If I give it to him early, his

head will swell up."

There is a ripple of laughter around the room, then Henderson,

realising the intensity of the Eastern European interviewer, adds,

“But seriously . . .” and embarks on a bland answer.

Another question comes his way: what does Joe think of the Verve

label? It’s about the third time the question has been asked and

this time the collective groan from other journos flown in from as

far afield as Japan, New Zealand and Europe shuts the question down

dead.

This is the 50th anniversary salute to the Verve record label, the

label to which Henderson signed two years ago, and the shy, bearded

saxophonist is just one of the star-studded panel which includes

Herbie Hancock, Betty Carter, young trumpeter Roy Hargrove, Antonio

Carlos Jobim and guitarist Kenny Burrell. Yet of all these,

Henderson, of worryingly fragile and birdlike frame, is attracting

the most attention.

That's what winning Grammy Awards does for your profile. Suddenly

- after a lifetime in jazz - Joe is an overnight sensation for

soundbite television and print journalists after a quick quote.

Henderson smiles warmly but, gentleman though he is, he deserves

better. He possesses, in the heading of a recent profile in the

influential jazz magazine Downbeat, “The Sound That Launched a

Thousand Horns”, has a career that dates back 30 years, has been

the consummate sideman on albums which featured jazz musicians as

influential as pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, trumpeters

Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard . . .

The list goes on and Henderson's CV is crammed with the stuff of

jazz legend. But more important for present purposes is his

commercial success.

In an art form where commercial success without artistic

compromise is a rarity, Henderson has pulled it off. His Verve

biography ludicrously overstates the case when it claims he is “the

most celebrated jazz artist of the past 25 years”.

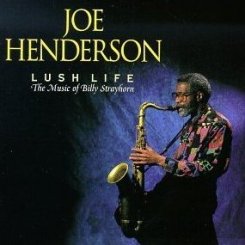

But there is no denying sales of 100,000 for his Verve debut Lush

Life; The Music of Billy Strayhorn in '92 (his first Grammy and

scooping multiple awards in Downbeat) or the even more successful

follow-up, So Near, So Far; Musing for Miles of last year which

pulled in Grammies for best jazz instrumental solo and best jazz

instrumental performance.

Henderson's name was again at the top of Downbeat and Billboard

readers and critics’ polls, and from New York‘s Village Voice and

Times through USA Today to the Grand Rapids Press and the Cleveland

Plain Dealer, his was the album that hit all the “best-of-the-year”

lists. Thirty years after topping the Downbeat poll as a “talent

deserving wider recognition," Joe Henderson was solidly placed

at the top of the Billboard' jazz sales charts. A star.

Jazz success, however, can be easily won -- Kenny G, for instance

-- but it usually doesn't sound like jazz. Kenny G, for instance.

But Henderson‘s albums are unmistakably jazz, crafted in the

classical framework and tradition.

He plays on both recent albums with small groups (Wynton Marsalis

appears on Lush Life, guitarist John Scofield on So Near, So Far) and

the consistency of his vision has been reinforced by the reissue of

some of his earlier albums in the wake of his current success.

The German label MPS recently reissued his 1980 album Mirrormirror

and there is the magnificent four-disc box set The Blue Note Years

which gathers together 36 tracks (mostly from the influential period

in the Sixties).

All are testament to Henderson's unswerving musical integrity, his

ability to play jazz without resorting to cliche or filibustering

solos and to his deep immersion in the various threads of jazz

throughout the decades. That sagging shelf of awards, trophies and

plaques is much deserved.

And he has often - like Miles Davis, with whom he once played very

briefly - worked with younger musicians.

“l like being with the ones who have done their homework,” he

says once free of the dumb leading questions. "They deserve to

be heard. They have to study the craft and take the music seriously.

It’s not just getting up and looking hip on the bandstand; the

music comes first and everything else comes after.

"There was a point where it seemed if you packaged it right

and put it in the marketplace in the right places, whether it was

ready or not, it seemed to be acceptable," he adds, referring to

the Eighties when record companies went on signing sprees looking for

the new Wynton Marsalis.

“Verve has at least moved away from that attitude and put some

integrity back into the music. I'm happy to be recognised the way I

have over the past year and a half, but I don’t do this for the

recognition. I do it because it’s what I'm supposed to do on this

planet, I enjoy what I do and I try to project that so the audience

gets a lot of happiness.

"But we have to look at the whole picture. Miles [Davis]

influenced this whole movement, just as Lester Young and others

before did. And all those who never got recognised. I don’t

appreciate them any the less for that [lack of recognition]."

What this late career success has meant, however, is that writers

and critics, most of whom should know better, are writing Henderson

up as the last survivor of his particular generation of jazz artists.

Henderson is far too modest and knowledgeable to suggest that.

He sees himself as part of a tradition and his two Verve albums,

the first a homage to the songwriter who for 30 years worked with

Duke Ellington, the most recent a respectful nod to Miles Davis, were

both projects he refers to as replanting the trees.

But this sudden flurry of attention for the albums, his invitation

to play at the Clinton Inaugural Ball, a South Bank Show profile,

numerous print interviews and sell-out live performances have cast

Joe Henderson of Lima, Ohio, as some Anthony Hopkins of jazz -- the

one who has always been there in workmanlike and creditable roles but

has only lately been accorded his due for carefully crafted albums on

his new label.

Hence the question: "What do you think of Verve, Joe?"

As the press conference winds down, Henderson takes his leave,

grabs a salad off the amply stocked side-table and settles into a

chair while television crews pursue Herbie Hancock for a soundbite.

He seems delighted to be able to talk about music and, as his manager

observes later, “You don’t get a five-minute interview out of

Joe".

He is a gracious and generous talker, and a gentleman who is

candid enough to admit the success now means he can get a good seat

in a restaurant. He exchanges a few words in Spanish to a Mexican

television crew and, like most jazz musicians who have found second

homes in France, can make small talk in French.

He has recorded in Japan, brought Afrocentrlc ideas to two famous

albums in the Sixties (Black Narcissus and Power to the People, both

with a hard political agenda), on the cusp of the Seventies spent six

months in the jazz-rock band Blood. Sweat and Tears (which he hated –

too repetitions, too many limos and too little music) and is now the

elder statesman of the melodic, mature and confident sound of

post-Davis bebop and ballads.

Joe Henderson has come a long way . . . but he remembers it all.

"I had no input into that Blue Note compilation because I'm

now signed to this other company,” he says, "but I take my hat

off to them. They did a beautiful job. I had a two-hour interview

flying between LA and Nice with the guy who did the liner notes and I

was surprised, as he was; just how much I could remember.

“When he was asking questions. the recording sessions seemed

like they'd happened the day before. But because they were so long

ago - the first one came from my first recording in 1963 - I can now

be objective about them."

Henderson's recall easily encompasses his first paying gig in New

York City. He'd previously studied at Kentucky State University for a

year and spent four years at Wayne State in Detroit where he played

alongside multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef and trumpeter Donald

Byrd.

During two years in the military he spent time in France where he

met jazz expatriates Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke. On his discharge in

'62, he settled in New York and hooked up with a bassist from

Detroit, Bernard McKinney, who showed him the ropes.

"I didn't know anything about the city but three months later

I was working my first gig and at the end the guy says, ‘Here Joe,

here’s your money.' It was $10 . . . and that went a long way in

’62. I’d gotten out of the military in August, so the gig would

have been in the Fall. There weren’t a lot of people there, but

just the fact I'd been hired for a gig in New York! I couldn’t

believe it and I’ll never forget it.”

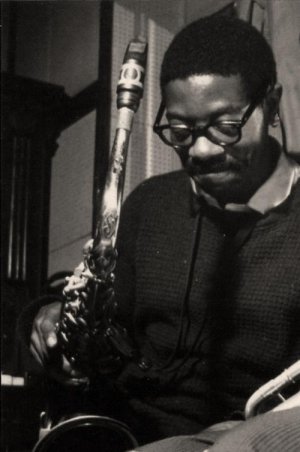

Within months Henderson was playing alongside trumpeter Kenny

Dorham on a Blue Note recording session -- another coup, given that

label's special place in jazz of the period. His own Blue Note debut,

Page One, was recorded in mid-1963 and Henderson was on his way.

He played on 30 albums by others and recorded seven under his own

name during that exciting decade of jazz where there seemed to be few

boundaries. Vying for eartime in the jazz community of the time were

the sounds of free jazz -- spontaneous improvisation which took as

its starting point Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz album of 1960 -- and

straight ahead hard bop. There was Third Stream with its classical

influences, the Afro-driven spiritual sounds of John Coltrane,

restrained experiments with time signature by Dave Brubeck and his

acolytes building on his Take Five album of '58 . . .

A broad freedom of expression was available in the jazz

vocabulary. And Henderson says he misses it these days.

“I’ve done some free things because there’s a part of me

that is a bit of an iconoclast and was especially so at that time.

Part of the spirit then was just to reject all that stuff like bar

lines and key signatures. We didn’t want to know about it.

“So part of the thing then was just to get up on the bandstand.

I became a little self-conscious about people coming in with their

own music and parts written out for everyone to play and totally

displacing what others might want to bring. I just said, ‘Let's

play' and didn’t want to interfere by even suggesting a title for a

tune.

“We'd just start playing and see what came out of it. We'd be

able to deal with it and figure out afterwards what we did. It was

such an interesting time and I don’t understand why that spirit

didn’t have a longer life.

"People like Albert Ayler [the seminal avant-garde tenor

player who died in 1970] aren’t around any more, of course. But

Ornette still is, although he’s much more traditional and

conservative than he was . . . and I‘m surprised by that. I was

asking someone just a week ago, ‘Whatever happened to ...’ and a

whole list came out of people who were connected with that free

movement who just seem to have evaporated ir vanished.

"Today there doesn't seem to be too much interest in that

free spirit of jazz where you just play and you don’t have to have

gone to this or that university to ensure we all know similar things

so we can make music together.

“That idea of saying, 'If you play saxophone, come on up and

we’ll figure out something’ seems gone now," he concludes

ruefully.

Doubtless that spirit of spontaneity was crushed in the Eighties

by what has become known as the “neo-conservative” movement which

had as its figurehead hot trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, whose insistence

on the correct, respectful attitude to the music often took on the

appearance of a political dogma.

Having sat out the Seventies after his Blood, Sweat and Tears

encounter as a low-profile jazz player, Henderson steadily worked his

way back to the forefront in a series of trio recordings during the

neoconservative Eighties.

As one who was there for that particular jazz the first time

round, he is surprised and saddened at the attitude of these younger

musicians whose market profile he hinted at it whose music often

doesn't match the claims made for it.

“I'm just surprised they seem so easily satisfied,” he says,

shaking his head with a bewildered smile. “They are satisfied just

to become the clones of the musicians of the previous generation.

They only want to be as good as that. In the Sixties we were

interested in pushing back those boundaries and adding something new

and coming up with ways and undiscovered avenues of interpreting and

improvising.

“We were young and excited by the possibilities - but today so

many younger musicians appear to be satisfied with just being as good

as the previous generations.

"I don't understand that spirit. I'm used to a much more

dissatisfied climate out of which comes some great melodies and works

of art oftentimes.

“The state of the art recording now is at a high level, although

some things about it haven’t really changed as far as my ear is

concerned. Sure, it’s gone from analogue to digital, so now it's

nothing for these young musicians to have their music in stores right

alongside the masters who are the mentors and influences. But how

could it be that you would put something out which isn’t quite as

good as that - but maybe just sounds better?

“I simply don’t understand that.”

If the neo-cons have been lining up to pay homage to those mentors

and influences – notably Duke Ellington (in the case of Marsalis

and his followers) and the early Miles Davis - then so, too, are many

of the more mature musicians tipping their berets towards Henderson.

Dumb leading questions by interviewers notwithstanding (“What do

you think of Joe Henderson?" directed to trumpeter Roy Hargrove.

Answer: "Well, he’s always been recognised by musicians . .

."), Henderson cops acclaim whichever way he turns.

Guitarist John Scofield - one of the finds of the Eighties who

didn't fit the neocon mould calls him “the essence of jazz” who

embodies “all the different elements that came together in his

generation: hard-bop masterfulness plus the avant-garde."

Branford Marsalis considers Henderson “one of the most

influential saxophone players of the 20th century" and young

pianist Stephen Scott, who plays on Lush Life, notes: "Joe uses

so much space when he plays and, as a piano player, you have to learn

to play in the cracks so that you won’t get in the soloist's way.

Joe starts in the cracks!"

Respect from peers has always been more important in jazz than

Grammles and critics' polls -- welcome though they may also be.

Tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, himself a musician like Henderson

who swam against the neo-con tides of the Eighties, offers the most

telling tribute to a man whose particular path has been unique in a

music that is by definition individual and unique.

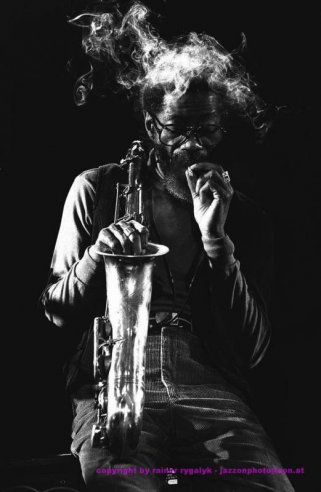

“he's always had his own voice,” says Lovano. "He's

developed his own concepts with inspirations of the people he dug but

without copying them. I hear Joe in other tenor players. I hear not

only phrases copped from Joe but lately I hear younger cats trying to

cop his sound. That's who you are as player: your sound.

“It's one thing to learn from someone, but to copy his sound is

strange. Joe’s solo development live is a real journey - and you

can't cop that! He’s on an adventure whenever he plays.”

But it’s an adventure with the attendant pitfalls of success at

this point. For a musician whose career spans the breadth of jazz

expression, he has latterly become known for his two most recent

tribute albums using the music of others.

He is scrupulous about according those musicians their due, but

the question remains: Where's Joe going with this?

"I’m thinking about another album right now,” he says

thoughtfully, "but we haven't settled on how we want to approach

it. If it’s another tribute, well, I’d have to say that formula

has worked well for me.

“They are great projects - Lush Life and Musing for Miles

couldn’t have been better, just beautiful music regardless. But if

I did another it would definitely have to be the last and I'd make a

l80-degree turn because there is such a danger in being typecast.

“And I’ve done so many different things in jazz over the

years.

“People say to me, ‘Look, that was all right - but we want to

hear your music now.’ I get that more often than anything else

these days. And when you‘ve had the success I`ve had recently, you

have to plan things out a little more. Unfortunately you can't just

go out there like a carefree spirit any more and have at it like you

used to."

He offers a broad smile and the lines around his eyes etch in

deeper.

Not like you used to?

“Yeah,” he laughs. “That's what success does for you!”

Joe Henderson's next album for Verve was in fact a tribute to Antonio Carlos Jobim (who also appeared at the Verve festival in his last live performance), and he also released his interpretation of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. He died of heart failure due to complications from emphysema in 2001.

post a comment