Graham Reid | | 10 min read

Keith Jarrett: Shenandoah

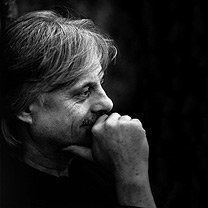

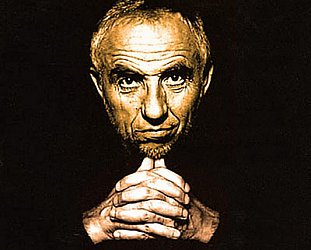

As much as a disembodied voice down a

phone line can, Manfred Eicher confirms the impression he made on

English journalist Richard Cook when he visited London in late ’89:

“He is a slim, rather careworn-looking man, whose great energy and

dedication don’t always break through a cautious temperament,”

wrote Cook, describing this founder of the German record label ECM (Editions of Contemporary Music).

“His small, shapeless face is

surmounted by a careless thatch of greying hair, his eyes have the

pale glitter of graphite; he’s not much given to laughing. But he

warms to anything he senses is kindred to his own beliefs.”

As befits the head of a company which

once carried the tag line “the most beautiful sound next to

silence,” Eicher seldom gives interviews . . . and on the rare

occasions he does, they are peppered with references to Kafka and

Beckett, the zeitgeist of recordings, and he draw analogies between

the music of saxophonist Charles Lloyd and a painting by Giacometti.

He counts among his friends film-makers

Jean-Luc Godard and Ingmar Bergman, is a businessman who can say

without being disingenuous, “I never thought about markets, I

thought only about tones and whether they moved me”.

He brings to the production of his

recordings the northern European aesthetic of the painter Edvard

Munch, whom he admires.

Guitarist Pat Metheny, now no longer

with ECM, says the only criticism Eicher ever made was “too

commercial." Has any other record company head honcho ever said

that to an artist?

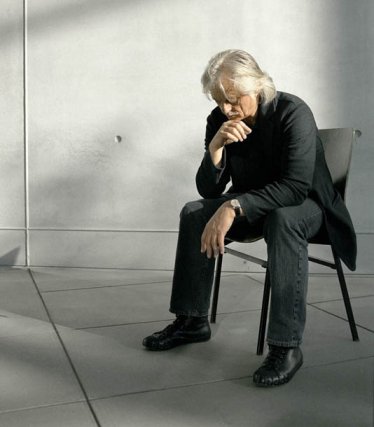

All of that makes Manfred Eicher –

whom Billboard called “a visionary” – a very interesting man

indeed. And very successful, too.

His ECM label has been, for 25 years,

synonymous with some of the finest jazz around. The label could

boast – not that Eicher would – that it launched the careers of

guitarists Metheny and Bill Frisell, pianist Keith Jarrett,

saxophonist Jan Garbarek and dozens of others.

Under Eicher – who considers the

music industry as “a kind of environmental pollution” – ECM

gave the breath of life in the late Seventies to American free jazz

outfits such as the Art Ensemble of Chicago long after their

home-base labels had abandoned them.

Today ECM’s back-catalogue contains

over 400 albums, and - since it launched its New Series imprint in

1983 - has commanded an audience in the contemporary classical world.

Many of the ECM albums are “landmarks in jazz and new music,”

Billboard observed last year.

In much the same way as Eicher gave

Jarrett (formerly a sideman with Miles Davis and Charles Lloyd) and

Garbarek (part of Karin Krog's band but a virtual unknown outside

Norway) the opportunities to extend themselves into spectacularly

successful solo careers, he started the New Series with Estonian

mystic composer Arvo Part.

So when, in '94 on ECM’s 25th

anniversary, the New Series sprang the enormously successful Officium

album by saxophonist Garbarek and the Hilliard Ensemble (over 250,000

copies sold - not bad for an album of airy, austere saxophone and

medieval chants) there was the feeling it couldn’t have happened to

a nicer bloke.

Happy anniversary, Manfred . . . and

congratulations on the success of Officium.

“Yes, I am always surprised when

people appreciate what we are doing,” he says in a voice as

measured and rapid as the notes of Officium are leisurely. “I never

think about market criteria, so could never foresee a success like

that. In the past we were often successful . . . but with Officium we

have something that is dark and light in the Beckett sense where we

have the juxtaposition of the two.

“You can feel the integrity of a

project and think it may touch people, but you never know these days,

there are so many layers, so many books and recordings coming out and

there's too much of everything.”

Eicher's point about the sheer volume

of artistic output today is one he articulates often; audiences see

too much and are too uncritical, reviewers (even those who acclaim

ECM releases) write less and less substantial and critical reviews,

with CDs reviewers jump from track to track and responses are

superficial . . .

In this regard the ascetic Eicher is

less like a businessman than a philosopher-musician . . . and his

background is illustrative.

Classically trained, the first record

he bought was “at the end of the Fifties, Klemperer recordings of

Mahler.” Pop music of the Beatles kind went right past him. (“I

noticed it but it never had an impact like chamber music and Miles

Davis.”)

He lived on yoghurt and coffee so he

could buy records, won a scholarship to the prestigious Berlin

Academy of Music, was a production assistant on recordings by Herbert

von Karajan, and indulged his abiding passion for jazz by attending

concerts and clubs.

In the late Sixties -- when rock

culture dominated the American music industry and jazz artists were

relocating to Europe -- he started ECM in Munich with money borrowed

from the owner of a local discount records shop.

“I was listening to people like

Omette Coleman, Paul Bley, Cecil Taylor and Bill Evans, but as far as

recording was concerned, nothing interested me. ESP Disk was

interesting,” he says, noting an avant-garde New York label. “But

they had a strange production quality because they were mostly

recorded in living rooms and didn't have the precise shape and sound

this music deserved.

“I wanted to do something from my

cultural background as a European with my awareness of what classical

engineers would do. I wanted to explore a different sound picture

than we had at the time."

The first album on ECM -- prophetically

titled Free at Last and by expatriate American pianist Mal Waldron -

appeared in 1970. The company pressed 500 copies and eventually sold

more than 14,000.

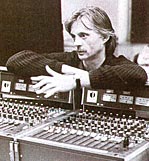

What impressed listeners then, as it

does today, was the clarity of Eicher’s production, one of the

label’s hallmarks. And as much as the “ECM sound” - pristine

clarity, a sense of space and feel for silence - garnered an

audience, so, too, did Eicher’s eye for packaging. ECM albums came

in austere covers often with chilly, atmospheric photographs of

barren landscapes that were stark and introspective parallels of the

music within. Very crisp, very European.

As Time magazine quipped about the

recordings in studios in Oslo: “for fun the musicians trundle off

to the Edvard Munch Museum.”

Eicher says the recording sessions

aren’t businesslike (“they are efficient,” he says efficiently)

but the musicians - many of them Americans, some such as guitarist

Egberto Gismonti from South America - are affected by the light and

atmosphere of Norway.

Eicher also exhibits an astute hands-on

tendency with his artists and over the years has built a reputation

for putting various players together in unexpected collaboration. The

Officium album which brought saxophonist Garbarek together with a

classical vocal quartet was typical.

He has put Brazilian Gismonti alongside

American Charlie Haden and Norwegian Garbarek with remarkable

results. He recorded jazz rebel Lester Bowie, exiled South African

pianist Dollar Brand, Indian violinist Shankar, bandoneon player Dino

Saluzzi ....

And developing careers rather than

picking up name players has always been the Eicher ethic: “So many

on ECM were not known or maybe just as sidemen. Jan Garbarek and

Keith Jarrett were not known in any kind of solo career, and putting

[vibraphone player] Gary Burton with [pianist] Chick Corea became a

new idea of pairing.

“Pat Metheny was a discovery for us,

Bill Frisell too. And I found Arvo Part in the middle of a creative

process. He was still living in Estonia when I heard him.”

But Eicher has also lost some off his

roster, notably guitarist Metheny, whose post-ECM career, it must be

said, has seen him become enormously popular but producing material

that barely hints at the depth of expression he achieved when he was

working with Eicher.

There are no long-term contracts

(expatriate New Zealand pianist Mike Nock recorded one album for the

label) and each relationship with a musician is based on “trust and

genuine respect for each other.”

And ECM’s list of superb jazz albums

is lengthy: Garbarek‘s minimal Places and Dis, the vigorous free

jazz on albums by the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarrett's numerous

live recordings including the weighty Sun Bear six-disc box set,

beguiling releases by cellist David Darling and vocalist Meredith

Monk, the late-career resurrection the label gave saxophonist Charles

Lloyd ....

It would be wrong, however, to say the label has been unimpeachable in its track record. While many releases are not commercially successful - a matter that Eicher treats as a minor consideration after artistic merit - the label seemed to come unhinged in the early 80s with releases by brain-numbing avant-rock outfit Lask and the exciting (but hardly ECMish) kiss-the-sky guitar jazz of the Everyman Band. Perhaps coincidentally, it was around the time Eicher was creating his New Series imprint to accommodate the likes of Part, the Hilliard Ensemble and others.

“Our music was very open from the

start. There was no dogmatic idea of what jazz should be. It was a

label for improvisers, and improvisation started in the 16th century.

So jazz was always only one part of it.

“But improvising to me means any kind

of musical idea that comes to my ear. The New Series started with

Arvo when we realised we needed a new label for that kind of music.

We’d already had Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians and

Meredith Monk’s [vocal] music developed from music that had come

from fragments of improvisation."

ECM's jazz imprint is not without its

critics, either: some have quipped that the label’s acronym stands

for Excessively Cerebral Musings, and the Eurocentricism it displays

has shifted the jazz co-ordinates for its predominantly white

audience away from the origins of this black music. Long on

cerebration, short on funk, said Time.

That view is simplistic, however, and

Eicher is unashamedly a product of the Continent. It also hasn’t

stopped him building a label that has numerous black American artists

(Sam Rivers, Old and New Dreams among many others) on its books.

“Music is such a universal thing and

I don’t like this term ‘world music’ where some pop producer

picks up African musicians and takes them to a studio in London and

makes some gesture to a tribal source. It's artificial. If you are

going to be true, you have to capture people in their own place.”

ECM has anticipated many movements in

contemporary music: the solo piano musings of Jarrett have spawned

innumerable inferior New Age pianists, configurations of artists from

various parts of the globe have found their parallel in present world

music trends of the kind Bill Laswell attempts, and the holy ambience

of Arvo Part has reached a popular audience through Henryk Gorecki

and John Tavener.

Even the ethereal melodic sound of

Garbarek’s saxophone has its diminishing return in Kenny G . . .

and some have noted that Officium was not an unexpected development.

It has been read as “Kenny G-meets the-Benedictine Monks of San

Domingo de Silos”, both of whom sold albums by the truckload. That

latter comment is spurious, however, and diminishes the vision that

Garbarek had when he brought the two sounds together.

And the consistency of Eicher’s

vision has been extraordinary - 25 years of quiet, uncompromising

independence and integrity almost unknown in the world of com-

merce and hard currency.

“ECM isn’t GRP and it’s not

Verve,” says Steve Vining, vice-president of sales and marketing

for RCA Victor/BMG Classics, which handles the label in the United

States. “But you can be very successful with this music as long as

you don’t try to market it as something it’s not. The tone of the

advertising is important. The key is to be innovative while keeping

consistent with the label’s special voice.”

Eicher is aware of what that voice is –

and money doesn’t buy or sell it.

“Major companies are always far

behind what the visionary small producers are doing. They can only

jump on a trend but very seldom do they create something. What makes

me feel good is that we could stay independent for 25 years in our

thinking. lt allows us to articulate a certain kind of musical

language that seems to have influenced many musicians and people.

“This is something special in the

world because it is based on the idea of artistic integrity and

artistic morality.”

post a comment