Graham Reid | | 4 min read

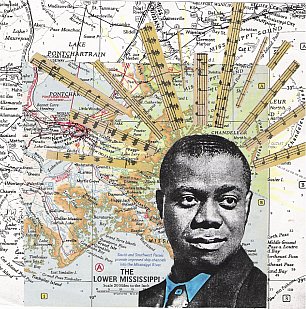

Louis Armstrong: Dear Old Southland (1957)

Duke Ellington famously observed there’s only two kinds of music, good and bad.

He may well be right. But there's also hey-nonny-nonny folk music, most of which frankly I don't consider music at all. It’s a mistake.

Most of my life I’ve managed to avoid folk - except for one year when I was asked to judge the category for our annual Music Awards. This was such a ludicrously hilarious suggestion (had these people never read anything I’d written about it?) that I accepted immediately. I faithfully listened to all the albums and came away more convinced than ever that this was dreary and earnest stuff lacking in all but the most forced humour.

My jazz equivalent is Dixieland: all those banjo players and clarinettists with their silly band uniforms of bow ties, loud waistcoats and straw hats. Of course there were always a few exceptions: a man would be a fool to dismiss Louis Armstrong, perhaps the most important musician of the last century, right? But by and large Dixieland never darkened my stereo.

Well, I had my epiphany and needless to say it was Ken Burns' Jazz series which turned me around.

To hear the original music placed back in its historical and cultural context meant that it rnade a whole lot more sense. So it wasn’t just guys in boaters on the back of a flatbed truck on a Sunday afternoon? As John McDonough’s essay in the Oxford Companion to Jazz points out: “Although history tends to condescend to Dixie today, in the late 30s it was still a significant, free-spirited and relatively contemporary alternative to what some saw as the regimentation of the big bands."

Of course before the 30s Dixieland - which essentially just meant the early New Orleans style - was one of the first distinguishable kinds of music that we would call jazz. lt was a clearly identifiable style by 1900 according to historian Charles Edward Smith, and in its staccato styte it appears to have been influenced by syncopated ragtime. It was about group improvisation (although there were exceptional solo musicians) and a chief feature was its lively pace.

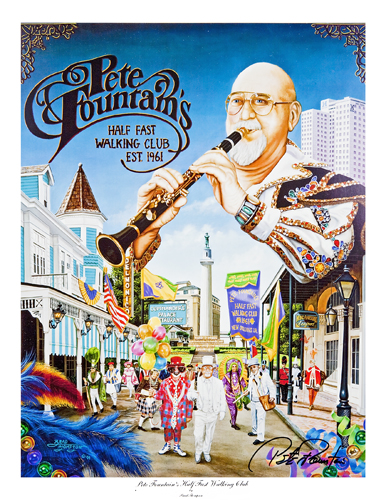

Part two of my Dixieland epiphany came with a series of four albums presented by one of New Orleans' finest practitioners of the style, clarinettist Pete Fountain. Fountain seldom rates a mention in most jazz histories, but he lived in New Orleans for all but a coupie of years of his life, had a well-known (if touristy) club there and is considered an authority on the style.

His CD series, Pete Fountain Presents the Best of Dixieland (on Verve), are separate discs featuring a disc each of Armstrong, trumpeter Ai Hirt, and himself.

There is also a compilation simply entitled The Best of Dixieland. Of course the Armstrong (earliest track is 1927, latest is 1958) is where any sensible, curious listener would start, and it’s exceptional. It’s also good fun.

On Back o’Town Blues Armstrong sings, "'I had a woman . . . " and a voice from the band says, "So what, I had 10". "Stop braggin' " fires back Armstrong without missing a beat.

There's a fine, seven-minute treatment of Basin Street Blues from 1958, where the clarinet of Peanuts Hucko weaves surreptitiously behind Armstrong’s assured trumpet lines, and there’s a lovely duet with pianist Billy Kyle (from 57) on Dear Old Southland.

The album is an easy entry point to the sound of Dixieland and covers some of the standards: Canal Street Blues, Muskrat Ramble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans and, yes, When the Saints Go Marching In.

Al Hirt, who died in 1999 aged 77, didn’t play with the gravitas of Armstrong and these days -- like Fountain -- is barely accorded a footnote in the books. He was classically trained and early on played in swing bands in the north.

He returned to New Orleans but the music had moved on and Dixie bands found it hard to get work. But in the Fifties he teamed up with Fountain (whoever got the gig became bandleader) and in '56 they recorded the material they'd been playing in clubs.

That album was Al Hirt’s Jazz Band Ball, recorded for Verve and produced by Norman Granz. It’s that which is reissued in this series, and it’s at its best in slower bluesy material like the straight-ahead Blue and Broken Hearted.

Partly because they played unfashionable music, Hirt has never really had his due outside of those who know the style. There’s ample evidence here he deserves better than a footnote.

The Fountain disc is Pete’s personal picks of highlights from a 100 album career and includes some great names such as trumpeters George Girard (who died at 26 of cancer) and Charlie Teagarden, and guitarist Bobby Gibbons (guitar a surprisingly uncommon instrument in Dixie bands.) Pianist Armand Hug (on the opener Mahogany Hall Stomp) is a reai discovery, and Fountain has a gorgeous tone.

The final 12 tracks on the 19 track collection come from Fountain's Mardi Gras Strutters recorded in 1963, and they sound as lively as anything from four decades before.

The 15 track Best of Dixieland collection includes material by Bob Crosby and his Orchestra, Armstrong, Eddie Condon and His Windy City Seven, Johnny Dodd’s Black Bottom Stompers and clarinettist Bob Wilber with Jack Teagarden, the trombonist with Louis’ All Stars in the Forties.

Selective picking says get the Armstrong then check out the compilation. After that if you’re hooked go for the Hirt then the Fountain. Some of this is very cool stuff.

It is vibrant, lively, surprisingly soulful and often just plain good fun.

Dixieland being played in my house? Who would have thought?

My friends look at me funny, and I don't care.

post a comment