Graham Reid | | 2 min read

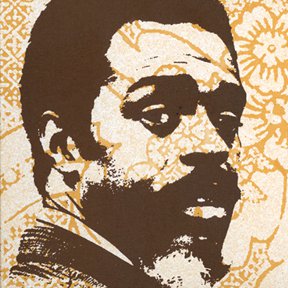

Albert Ayler: Our Prayer

Albert Ayler -- the inspired, heroic, driven and sometimes difficult saxophonist who committed suicide in 1970 at age 34 -- still stands at a crossroads in jazz.

By the late Nineties – when an exceptional, expanded edition of Ayler live surfaced -- even the music's most ardent advocates were having to concede that jazz was almost an historical artifact.

“Contemporary jazz” in the age post-Wynton Marsalis' neo-con movement sounded increasingly like an oxymoron as various styles, just as in rock, were recycled and remodeled in imitation of earlier eras.

It was almost as if every avenue had been explored and now slavish replication had become the acceptable substitute for innovation.

The question remains; why would you buy an album by trumpeter Roy Hargrove, good though he may be, when you could get Miles Davis doing something better 30 years ago.

If the only way ahead is by looking at where you’ve been, then jazz – at that time and even today – could do no better than look at the time it hit crucial crossroads , the late Sixties.

At that junction artists such as Ayler took the contract of jazz quite literally and extended hard bop into free jazz, a style in which many would say the music reached its purest expression. It was collective improvisation by individuals who may, or may not, choose to draw on any preceding era and style.

Free jazz is difficult (sometimes it’s awful and the name used as an excuse to just noodle around) but often it catches the performers at the peak of inspired, unedited inspiration. It didn’t take an audience with it, but today the parameters are different.

Popular culture today now accepts artists with magpie tendencies. (Will the real Beck please stand up? Oh, you are.)

And pure noise has become part of the available musical palette (Yoko Ono, Sonic Youth, the Dead C).

All that might make Ayler a more accessible proposition today. Although I doubt it.

Experience tells me he’s more

accepted by a rock audience (which often only hears the

parent-baiting aspects) than jazz listeners.

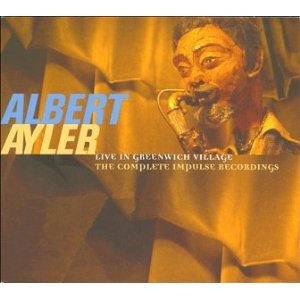

Ayler was no sideshow freak: his pure, unfiltered improvisation was grounded in various traditions and the double disc Albert Ayler Live in Greenwich Village of '99 captured him at his best as he incorporated peculiar marches and New Orleans ballads, quotes from show tunes, and traditional American melodies into a swirling personal journey. These recordings were pulled together from performances in Village clubs between March '65 and February '67.

Those who doubt Ayler’s serious intentions and just hear untutored noise and squawking need only look at the titles here: Holy Ghost, Truth is Marching In, Our Prayer, Spirits Rejoice, Divine Peacemaker . . .

With bands consisting of bass (sometimes two), drums, cello, sometimes violin and his brother Don on trumpet (but only one track with piano), Ayler stripped his sound back to its elemental essences.

He heard music in interlocking melodic instruments but kept the rhythmic undercarriage as wide-spectrum and open to equal invention.

After Ayler there seemed nowhere else for jazz to go, which is why he is so important and could be such a source of inspiration today. He opened a door through which few entered.

Some of the tracks on this double disc appeared as the single album Live in Greenwich Village about which the formidable Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD trumpeted, “if his reputation hangs on any single recording, it's this one”. And now there is more of it.

'Nuff said.

Enter at your peril – pleasure.

post a comment