Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra: St Louis Blues (1929)

Because we listen to the jazz of the Thirties and Forties at such an emotional distance, it is almost impossible for the 21st century, iPod-carrying, cool post-modernist to feel something -- possibly even anything -- of what so affected those who heard it as fresh, exciting, innovative and daring at the time.

It is hard to sell the idea, let alone the music, of Benny Goodman or even Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five with their three minute minatures to jazz listeners who these days expect musicians to be just hitting their stride around that mark and really cutting loose about five minutes later.

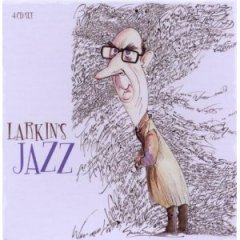

The poet and jazz enthusiast Philip Larkin (1922-85) insisted the jazz of Thirties/Forties "made life sweet" and in the liner notes to the joyous and often disarmingly exciting four CD collection Larkin's Jazz (Proper) he is quoted as saying "I can live a week without poetry but not a day without jazz".

Larkin put jazz artists like Sidney Bechet, Goodman, Armstrong, Count Basie and Bob Crosby into the same elevated realm we might think he would reserve for the inspirational poets.

But to him these players were like poets, their words were notes which evaporated into air, mischievious, dancing, ephemeral and swinging.

The jazz musicians were poets whose work lifted the spirit and spoke of the spectrum of human emotion. They also made music which was just enjoyable, as plain and simple as that.

As with many people -- those children of the Sixties who cannot let go of the music of that era -- Larkin remained loyal to the soundtrack of his youth, those 78rpm records which brought an imagined, colourful America into his black'n'white England.

But he was assiduous in his collecting and listening until circumstancess in '44 when he was 22 (and fell in love) made it impossible.

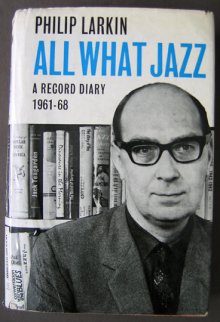

Larkin later reviewed jazz (mostly that of his formative years) in the Daily Telegraph and was knowledgeable and pointed in his comments.

But bop, for him, was a style too . . . He just didn't like it -- and said so.

He would repeatedly ridicule artists like Coltrane: "the master of the thinly disagreeable [who] sounds as if he is playing for an audience of cobras".

But his appreciation of the jazz of earlier years was so deeply informed by personal experience and the thrill of discovery you had to respect his taste and superior understanding.

He could sometimes bring the poet's imagination to his criticism: of Ben Webster's playing with Art Tatum on Have You Met Miss Jones ('58) he wrote, he was "breathing out melodies with accomplished negligence".

Larkin died 25 years ago and the Larkin's Jazz collection -- beautifully presented with excellent essays and notes on the songs and artists -- allows us the chance to try to hear again the music as he once did.

The first disc -- which opens with Ray Nobles' Tiger Rag from '32 and the first record Larkin owned -- is entitled I Remember I Remember. It includes early Armstrong (Ain't Misbehavin', Knockin' A Jug, Squeeze Me) along with Count Basie, Bessie Smith, Bob Crosby's Bob Cats and Coleman Hawkins and His Orchestra with Body and Soul from '37.

Disc two is Oxford, the music Larkin heard and collected when he went to the university in 1940: Eddie Condon, Louis Prima, Pee Wee Russell's Hot Four, Art Hodes, Harry James . . .

The third disc is All What Jazz and takes its title from the '71 book of his collected jazz writings: King Oliver, Sidney Bechet, Johnny Dodd's Black Bottom Stompers, Armstrong again, Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington among them.

The final disc is entitled Minority Interest and is music that Larkin and his friends would listen to at their homes in Hull (Eddie Condon, Jimmy Witherspoon, Dave Brubeck) where a lot of booze was drunk.

"Listening to new jazz records for an hour with a pint of gin and tonic is the best remedy for a day's work that I know."

Curiously for a poet so inspired -- and taken out of himself -- by jazz, Larkin seldom mentioned it in his verse.

But this intelligent and frequently exciting collection does include his lines from Reference Back, written in '64.

And just as Van Morrison would refer to the inspirational, uplifting and seemingly spiritual music of his youth coming through the radio, you can hear the love and excitement Larkin also felt, in this instance for Riverside Blues of 1923 by King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band . . .

"The flock of notes those antique negros blewout of the Chicago air into

A huge remembering pre-electric horn

The year after I was born."

post a comment