Graham Reid | | 2 min read

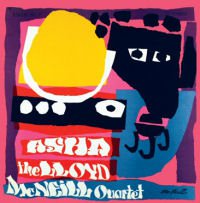

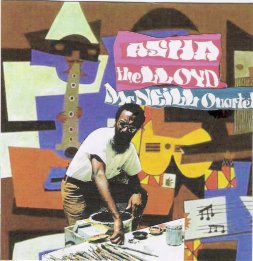

Lloyd McNeill: As a Matter of Fact

Jazz flautist Lloyd McNeill lived the

kind of life only possible in his era: he counted among his friends

in the Sixties and Seventies Pablo Picasso (when they both lived in the south

of France, McNeill also being a painter), jazz musicians such as

Cecil McBee and Ron Carter, singer Nina Simone and many in the Civil

Rights movement.

He spent time as a Navy reservist, was

well-traveled (West Africa and Brazil), played in a band with expat

Ethiopian saxophonist Mulatu Astatke, studied under Eric Dolphy,

became a university professor . . .

One of those annoyingly gifted,

inter-disciplinary types – poet, painter, photographer, composer,

performer, writer, you name it – he also founded his Asha music

label in 1969 on which he recorded his often groovy, spiritually cool

and hot swinging funky jazz.

That said, you'd be forgiven for not

ever having heard a note: the reissued Asha by the Lloyd McNeill Quartet

originally only had a pressing run of 1000.

Once you take out copies for friends I

suspect damn few even appeared in the stores of his hometown of

Washington DC, let alone in a bin near you.

Listened to at this distance – 40

years on – the album evokes that era when swinging flute was a

frontline instrument (for Dolphy, Charles Lloyd, Herbie Mann and

others) and the jazz contract hadn't been yet extended into jazz-rock

fusion.

Here the quintet – which includes hot

pianist Gene Rush, and bassist Steve Novosel who went on to play

alongside Rahsaan Roland Kirk, McCoy Tyner, Sonny Rollins and other

jazz giants – looks to Thelonious Monk (on As a Matter of Fact)

and Latin influences, as much as swirling post-bop.

And the closer is a 10 minute evocation

of Warmth of a Sunny Day. It is certainly that as McNeill's breezy

flute weaves and skitters like a leaf in the wind.

But he also ploughs deep into a groove

for Dig Where Dat's At, a 3.30 slice of the kind of jazz-pop which

could appear as the theme to a particularly switched-on arts

programme on television. The title track is a very cool (emotionally

and metaphorically) piece which owes a little to the soaring quality

of Indian flute music.

What isn't here – and no one says it

has to be – is some sense of the turbulent political era in which

this album appeared: 1969 was an explosive one for black Americans

and yet McNeill's music doesn't touch on it.

Perhaps at the time he was offering

music as a balm.

In that he might not have succeeded at

the time, but he does now.

Asha is not a lost classic, but it is certainly an album that deserved wider currency than his small indie label could offer.

That it has finally been given that is

excellent news indeed.

post a comment