Graham Reid | | 4 min read

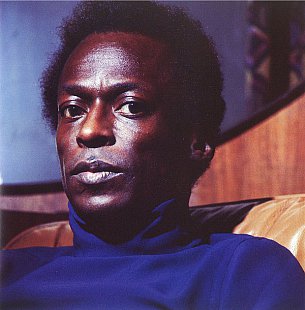

Miles Davis: Spanish Key (single edit)

Carlos Santana, who says rarely a day

goes by when he doesn't listen to some Miles Davis, believes you only

have to listen to the Davis' album Live at the Plugged Nickel --

recorded in December 65 at a Chicago club but not released until '68

-- to realise the trumpeter had exhausted standards such as Stella

By Starlight and On Green Dolphin Street, and even

his own classic So What (from Kind of Blue).

By

the late 60s Davis, always a restless spirit, was looking

around and listening to the sound of the street. Rock bands and

soul-funk outfits were connecting the black communities and a younger

generation in a way he, in his early 40s, no longer was.

Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix had more to

say to young people than he did, and in retrospect his albums such as

Filles de Kilimanjaro and In a Silent Way of 69 edged

towards electronics and the fusion with rock which would follow.

Encouraged by his younger wife Betty –

a soul-funk singer who was also sharing her favours with Jimi

apparently – Davis was introduce to rock music (Hendrix in

particular with whom he was scheduled to record at one point). And

with electric guitarist John McLaughlin and keyboard player Joe

Zawinul recruited for studio sessions which became In a Silent

Way, Davis began to break free of the constraints of acoustic

jazz and standards.

And whereas in the past he would have

producer Teo Macero wipe unused takes, in 69 he insisted Macero

record and keep everything that happened in the studio. This paved

the way for one of the most innovative and daring albums of Davis'

career, Bitches Brew released in late 69 which saw him shear

away from the jazz of the past.

Bitches Brew was the album – a

double at the time in a cover by the same artist who had done Santana

and Hendrix sleeves – which alienated his conservative jazz

audience but took him to sharing stages with rock bands such as the

Steve Miler Band, Neil Young and Crazy Horse, and Santana at places

like the Fillmore East.

Yet Bitches Brew is not a rock

album – although the way Macero pieced together segments of tapes

from the sessions was increasingly common in rock after Zappa's Freak

Out! of 66 and the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's of the following

year.

The Brew music stands on a cusp

between jazz and rock: evocative and atmospheric, edgy (angry in

places even) and abstract. This music isn't, as jazz critic Greg Tate

writes in the liner notes to the Legacy Edition reissue, “in much

of a hurry to arrive anywhere, it creeps, unspools, staggers and

sprawls in pursuit of an improvisational New Jerusalem more concerned

with atmospherics and strangeness than momentum”.

For those who like their music to have

resolution, Brew is still a tough call.

At the time the respected critic Ralph

Gleason, a Davis defender, joked to Macero after receiving some

advance tapes, “No wonder jazz is dead. Guys like you are killing

it.”

Macero snapped back: “ I may have killed jazz, but I have

established a new kind of music. What have you done lately?”

A “new kind of music”? True.

Where much of the fusion jazz of the

70s which followed – McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra often being

a prime offender – was flat tack and headstrong, Bitches Brew

lays out foundations slowly, the guitars, Davis' trumpet and the

electric piano of Zawinul weaving stealthily.

In the studio Davis assembled a large

cast, among them the angular drummer Jack DeJohnette alongside Lenny

White, electric bassists Dave Holland and Harvey Brooks, Bennie

Maupin on bass clarinet, Chick Corea on electric piano alongside

Zawinul . . .

This idea of double quartets had been

previously explored by Ornette Coleman on his Free Jazz album of '61,

but Davis wasn't seduced by the drama and sonic clashes of free jazz.

Melodies were still important, although here they are often

truncated, slide in another direction, are picked up by different

instruments, left to hang.

The music on pieces like the 20 minute

Pharaoh's Dance, the 26 minute title track and the 14 minute

Miles Runs the Voodoo Down unrolls and weaves in and around

itself. It was quite unlike anything else at the time, and very

little since.

Because of that Bitches Brew –

a masterpiece of assemblage by Macero who also employed loops, delays

and reverb which were uncommon in jazz then, and are even today – has a timeless

quality, unlike some of the urban funk Davis would pursue on

subsequent albums like On the Corner which sound grounded in

the early 70s.

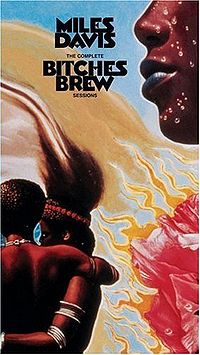

In 98 a four-disc set The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions was released (right), but that might be too much for most listeners.

The Legacy Edition is a double disc of the original album with alternate takes and single edits (proof to Davis' critics that he was trying to get to the pop market).

There is also a

previously unreleased DVD concert film of a snappily dressed Davis in

late '69 in Copenhagen with Shorter, Corea, Holland and DeJohnette

playing some Brew material but also keeping one foot back in

standards (I Fall in Love To Easily). The concert footage

shows how hard this music was to replicate successfully on stage and

confirms that Bitches Brew was a studio conception.

Later in life Davis took up painting

and many of his works were acclaimed. Davis was a painter in sound

also, Duke Ellington calling him “the Picasso of jazz”.

As Richard Cook and Brian Morton note

in their Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD he left “some

masterpieces, some puzzling abstract and a pile of fascinating

sketches”.

The colourful, fragmented but unified and engrossing Bitches Brew is one of his masterpieces.

.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

post a comment