Graham Reid | | 5 min read

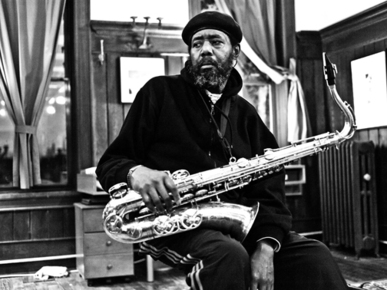

David S Ware: Sweet Georgia Bright

When the histories of jazz in the 20th

century are published one name from the last two decades could loom

unnaturally large: Wynton Marsalis.

In some books he'll be hailed as the

man who saved jazz from factionalism, commercial isolation and the

like. In others he'll be the revisionist who used unquestionable

talent, persuasive intellect and immense personal charm to

marginalise artists and styles his precociousness and dogmatic

attitude chose to dismiss. Count me with the latter.

On many levels I admire Marsalis. When

he first came to New Zealand it was my pleasure to interview him and

then we wandered around Wellington's Michael Fowler Centre together

chatting about Miles Davis’ health, where all this was going, the

attitude and so on. Real nice guy.

I've seen him play and have interviewed

him a few times since. I believe I've honestly reported what he says,

and because he’s much more amusing than his words appear in bare

print, I've faithfully tried to represent that.

But I've also added a little necessary

corrective gloss. I've certainly mentioned his extensive catalogue --

what is it now, 40 or 50 albums? -- seems scrupulously free of what

we might call memorable compositions.There's also no great pool of

musicians who want to perform his stiffly reverential material.

Maybe at the end of this particular

century when other books are written, Wynton will be seen as the

Boswell to much bigger Johnsons, if you get the dick-swinging

analogy.

This media savvy son of the late 20th

century initially re-positioned jazz back into parameters Miles Davis

set in the early 60s -- which Davis abandoned. As Wynton had too when

he realised dogma is fine, but music doesn't stand still. What

Marsalis discovered after studying Davis' Sixties suits and sounds

was that from there you had to go either forward or back.

He persuaded many people going back was

better. He now offers a passage to Duke Ellington.

Well cool -- and it is, really

terrific. But?

Wynton may not like, for example, the

jazz fusion of Davis, Weather Report, Al DiMeola and others. Fine.

However he forgets or ignores that most

people didn't and don’t like it either and are selective in their

listening to it.

But that doesn't mean it didn't exist

or some good didn't come out of it. It certainly seems to be as

influential on young players as Wynton once was.

More so perhaps.

What irritates most about his

revisionist and contagious attitude is many styles cf jazz -- and I'm

thinking specifically of free jazz now -- are not only written out by

omission, but that it consistently considers them a side issue: “To

be abstract means to be abstract, that's all,” Wynton said to me in

January 2000.

Yeah, and...?

Sure it's just another style. But it's

been a damn important vehicle of expression, especially for black

artists like the fiery Revolutionary Ensemble, the musico-political

lightning rod of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, towering individuals

such as Ornette Coleman, Anthony Braxton, Leroy Jenkins, Cecil

Taylor, Albert Ayler...

Free jazz extended the contract John

Coltrane wrote and – revisionists notwithstanding -- it hasn't gone

away.

One of its most long serving

practitioners as the millennium turned was 51-year old, nerve-ending

tenor saxophonist David S. Ware.

Born in New Jersey and schooled in

Cecil Taylor's bands in the mid-Seventies, he possesses that spiritual

impulse which drove Coltrane, speaks of sciences as chess master

Braxton might, and makes sometimes extraordinary music. Oh, and if

you think rock connections somehow confer status on a jazz musicians:

he's opened for Sonic Youth.

So that probably means he's okay,

right?

Better than that, he makes muscular

free jazz that connects with and extends the lineage of Coltrane,

Braxton, Taylor and Arthur Blythe.

Ironically – or just coincidentally –

he was on Columbia alongside Wynton, and was introduced to it by

Branford, a man with more catholic taste and a democratic attitude to

music than his brother.

Ware's album at the time was

Surrendered, a real broad-screen affair.

It was as out-there as his previous

stuff, which made it the ideal starting point of free jazz was

outside your orbit and you were curious.

Of course the upshot was some critics

expressed the customary qualms which aficionados and bores do about

most idioms whether it be punk, country music or razor gargling. Oh,

he's sold out. Just look at the title!

Let's give the artist some credit. This

isn't a Rod Stewart or All Saints career move.

It's an album by a man who had played

this music for 30 years and he made the album he wanted to make. You

can't apply the litmus test of what his critics wanted him to make

wanted him to make. (It's usually more of what they liked before.)

Consider instead Surrendered for what

it is: an approachable way in to free jazz.

There are recognisable tunes, yes. But

that's neither buying in or selling out. It bridges the gap between

interminable illiterate soloing (leave that to those who think “free”

means making it up as you go along) and the real revolutionary spirit

which drives this music.

Ware points out in the liner notes that

free jazz isn't free, it comes at great cost. There are no hit

records or Grammys, praise and gratitude come from those who get

what's going on, and nearly 40 years after Coleman, Coltrane,Taylor

and Albert Ayler tore down the walls of harmonic and rhythmic bias,

“the standard reactions are still scorn, disbelief and dismissive

apathy. In other words you pay to play it”.

Gee, I wonder who might need to be

reminded of that?

When the histories of 20th century jazz

are published, here's a tip: Turn first to the pages about free jazz.

If there aren't many or it is given cursory treatment wait for a

better, more honest one.

Chris - Oct 11, 2010

Thanks... the quartet with Shipp, Parker and either Susie Ibarra, Guillermo E Brown or even Marc Edwards on drums is truly epic. Check out the new trio recording on Aum Fidelity called Onecept... i haven't yet: so much to hear, so little money:)

SaveAngela Soutar - Jul 5, 2018

Good to hear that judgement on W. Marsalis. I've always felt a little guilty for not liking his work, despite all the hypey kudos he's been given.

Savepost a comment