Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Dave Brubeck Quartet: Three To Get Ready (from At Carnegie Hall, 1963)

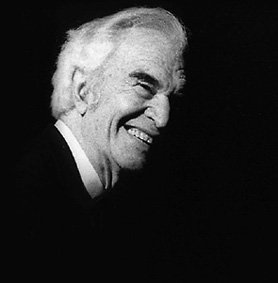

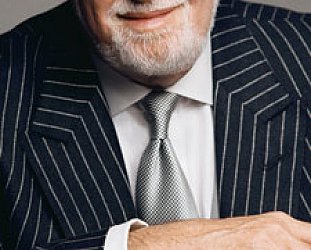

Dave Brubeck, whose hit album in 1958

was Time Out, understands time better than most of us. In December

2010 he turned 90 and although ailing, as expected, he had been

playing right up until his late 80s – and been collecting awards

and accolades.

For many jazz listeners and critics

Brubeck was always considered an intellectual rather than an

instinctive musician, although the idea of native talent accounting

for greatness in jazz is condescending and denies the musicians'

intellectual capabilities.

Try telling Wynton Marsalis, or any

black artist, their art is instinctive and see how far you get. Kinda

racist really, isn't it?

That said, Brubeck was a jazz scholar.

He studied with Darius Milhaud, experimented with classical idioms in

jazz, took his jazz investigations into what we now call world music,

and put the idea of shifting time changes at the forefront of his

playing.

But he also committed that most grave

of jazz sins: he became popular. The jazz world is a weird one, much

like indie-rock: commercial success works in direct relation to the

words "sell out." Ask George Benson or Charles Lloyd.

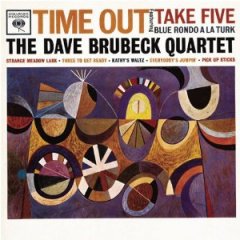

Yes, Brubeck had A Hit. It was the

clever, memorable and innovative Take Five from that equally canny

Time Out album. That was enough for many jazz critics who, from then

on, could cheerfully dismiss him.

Brubeck's early career repeatedly

received a record-company massage from his grateful label

Columbia/Sony: there was the box set Time Signatures in the early

Nineties and a decade later the simultaneous release of three

remarkable albums: Red Hot and Cool from the mid Fifties, the double

disc recorded live at Carnegie Hall in 1963, and Jazz Impressions of

Japan from '64.

There was also a collection of the

pianist with singers such as Carmen McRae, Louis Armstrong, Tony

Bennett and even Peter, Paul and Mary. It wasn't that interesting,

but no matter. The others sound as fresh now as yesterday, if

yesterday was that time when jazz, rather than rock and pop, was the

language of the American sophisticate, the late Fifties and early

Sixties.

These three albums -- remixed,

remastered, re-annotated -- present an essential cross-section in the

early career of Brubeck, most with his famous quartet, the other

members of which were drummer Joe Morello, bassist Eugene Wright and

the signature saxophonist of Brubeck's sound, Paul Desmond.

Brubeck might have been the

buttoned-down married guy who played piano in the music room and

looked like he'd stepped out of a Life magazine ad for Studebakers,

but Morello came off as the moody, inner-city dreamer who would write

melodies for Audrey Hepburn or a girl he saw on the streets of Tokyo.

And on Jazz Impressions of Japan, with Desmond on shakuhachi-styled alto (notably on Fujiyama), you can hear the romance and longing this formidable quartet could conjure up.

But as with the perpetual Lennon/McCartney divide -- with one the cynic and the other the romantic -- this simplistic separation between Brubeck and Desmond doesn't quite stack up.

On Jazz Impressions of Japan there's a

fragmented sense of yearning in Brubeck's playing on Fujiyama, while

Desmond seems to go through predictable changes on Osaka Blues.

Elsewhere Desmond pulls off remarkable depth of meaning while Brubeck

simply hammers out those famous block chords.

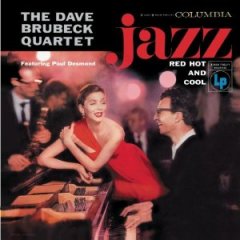

Red Hot and Cool takes its title from a line of lipsticks Columbia was cross-promoting at the time (check the cover) but captures Brubeck and band cutting a fascinating, almost elitist, phraseology into jazz.

Time changes peppered the music, his

classic tune The Duke (which Miles Davis among others covered) is

here, and there's even now a feeling of boundaries being ridden and

the jazz envelope being opened for scrutiny.

The most exciting album in these

welcome reissues is from the date at Carnegie Hall. As on the best

live rock albums -- Dr Feelgood's Stupidity, Frampton Comes Alive and

Thin Lizzy's Live and Dangerous for example -- the audience is part

of the experience.

To hear a crowd bay with delight, to

feel the vigorous bounce of Desmond and Morello locking together, or

the restrained intelligence Wright displays on Bossa Nova USA, is to

be transported to another realm -- and era.

Brubeck's music was intelligently

driven by a repository of musical knowledge and, perhaps better than

all that, thoroughly enjoyable.

Might be nice to discover, or rediscover, him before time -- that guiding principle of his music – overtakes him.

post a comment