Graham Reid | | 5 min read

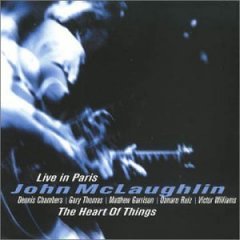

John McLaughlin: Seven Sisters (from Live in Paris, 2000)

The opening track on guitarist John

McLaughlin's Live in Paris, usefully serves as a microcosm of his

career. It starts slow, melodic and considered with McLaughlin

peeling off memorable phrases, then picks up speed to hit a furious

pace as he skitters around the fret-board like ferret freebasing.

Things then cut back to irresistible

refinement as it gathers in its melodic sharpness again, and seems at

ease with itself as it lopes comfortably home.

Yep, that's about the career-so-far of

68 year old McLaughlin.

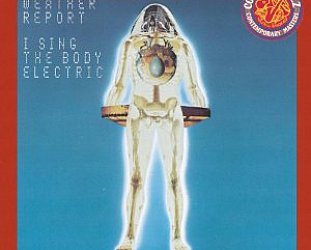

McLaughlin came to wide attention when

he played on Miles Davis' seminal In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew

albums in the late Sixties. And then he became the greatest living

exponent of jazz-fusion when he formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra,

which was, to be blunt, as revolutionary as it was sometimes

unmitigated shit.

With McLaughlin’s incendiary guitar

leading the way, MO redefined the parameters of jazz-fusion which

Davis had laid down -- but it also introduced the word 'migraine' to

the jazz vocabulary.

McLaughlin and violinist Jerry Goodman

could not only play faster than anyone on the planet, night after

night they seemed determined to prove it. And the most scary thing?

These guys weren't cracked-up to the frontal lobe, they were as

straight as a nun in traction

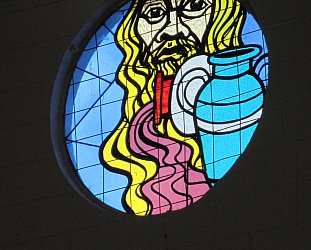

That's what having a guru meant back in

the early Seventies: intensity, and not much fun.

McLaughlin's subsequent group Shakti

was where he started making sense and his three mid-Seventies albums

under that band name plus his much under-rated Electric Guitarist

album of 78 (with guests Carlos Santana and players such as Chick

Corea whose careers were in jazz, not rock) were almost an apology

for what went before.

McLaughlin is one of those guitarists

for who the technically impossible is effortless. Fortunately – unlike

Joe Satriani and Yngwie Malmsteen and those guys Guitar Player

magazine keep banging on about – he came from blues/jazz and so had

models and mentors along the way. The rock guys had to rely on their

own pool of ideas. And look where that got them, huh?

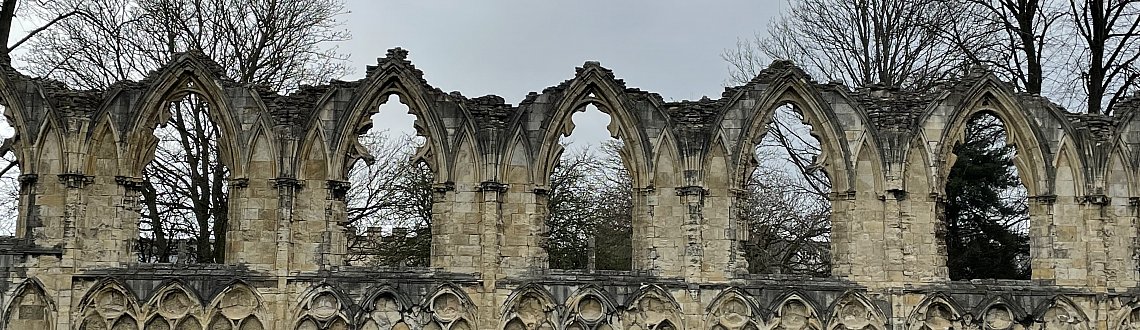

Yorkshire-born McLaughlin's mother was

a violinist, his siblings are all musical, he's mostly self-taught

and studied blues players as a pre-teen.

He moved to London to play in bands and

loose units alongside the likes of Clapton (who was but five years

away from being proclaimed God) and, like so many of his peers, was

smitten by the genius of sitar player Ravi Shankar. He became

attracted to eastern philosophies and music.

His debut album Extrapolations of 69

with John Surman (saxophones), Brian Odges (bass) and Tony Oxley

(drums) is considered a classic of the decade and a summation of the

small group playing of the time.

It also anticipated jazz-rock fusion of

the Seventies, which is doubtless why he ended up with Davis just as

the great trumpeter was about to redefine jazz again, this time

incorporating rock's mannerism.

After Davis, McLaughlin took fusion to

its often-illogical conclusions with the spiritually inspired

Mahavishnu Orchestra. It went too fast to last and, despite reviving

the concept after a brief hiatus with French violinist Jean Luc Ponty

in the place of Goodman, it seemed all over bar the screaming

headache.

After Davis, McLaughlin took fusion to

its often-illogical conclusions with the spiritually inspired

Mahavishnu Orchestra. It went too fast to last and, despite reviving

the concept after a brief hiatus with French violinist Jean Luc Ponty

in the place of Goodman, it seemed all over bar the screaming

headache.

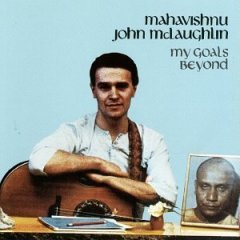

The Orchestra did leave behind two

excellent albums however, The Inner Mounting Flame and Birds of Fire,

although my pick is the much more measured My Goals Beyond from 1970.

The way out of electric hot-rodding

proved to be Shakti, an Indo-jazz group which had the same energy,

pace and virtuosity of the MO, but which reined it in through

memorable acoustic music, and allowed the guitarist (on a specially

constructed instrument to explore the nuances of Indian microtones

and scales.

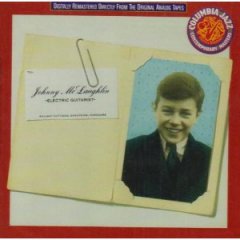

By the late Seventies he was keen to

reposition himself musically and within the market: Johnny

McLaughlin, Electric Guitarist -- which wittily came in a cover with

a reproduction of the business card he had a kid in Yorkshire -- put

him squarely back in the jazz business.

By the late Seventies he was keen to

reposition himself musically and within the market: Johnny

McLaughlin, Electric Guitarist -- which wittily came in a cover with

a reproduction of the business card he had a kid in Yorkshire -- put

him squarely back in the jazz business.

Throughout the Eighties his path was

like a mature reconsideration of where he had been: he played

exceptionally well received acoustic concerts with Paco De Lucia and

Al Di Meola (their live One Night in San Francisco of '80 was a huge

seller), played on Davis’ You’re Under Arrest, revived the

Mahavishnu name, undertook commissions for guitar concertos, worked

with tabla drummer Trilok Gurtu and then, in the early Nineties, put

together an excellent trio with organist/trumpeter Joey DeFrancesco

and drummer Dennis Chambers.

That was the line-up I saw in the

mid-Nineties at one of those famous New York clubs. As a fan of some

of his by-then almost 30 year career there were a lot of questions I

wanted to hear answered.

But to be honest, the big stupid one

was simply, will he play really really fast?

But to be honest, the big stupid one

was simply, will he play really really fast?

And you couldn’t help note that as

the night progressed the note count was climbing.

Good ol' Johnny, if there were more to

be said, he'd say it.

In one way his Live in Paris album is like Electric Guitarist and The Promise of '95 in that

it too summed up and explored again various sides of his personality:

a lovely ballad in Fallen Angels, intelligent fusion, and on Mother

Tongues he and the small ensemble revive the best of the lightning

spirit that was the Mahavishnu Orchestra. It wasn't the best album of

his career but was some considerable distance from his worst.

In a way it is a small primer of a long career, but worth investigating for

its own sake.

A microcosm, if you will.

And sometimes it goes really really

fast.

Mike P - Aug 5, 2021

I have quite a number of Mahavishnu Orchestra albums and a number of John's solo work or work with other musicians such as Carlos Santana. I think the album Electric Guitarist is a great album, so how come it got a summary of underrated? Did not sell well maybe? I have also just finished reading Carlos Santana's auto biography 'The Universal Tone' where there are numerous references to John, Mahavishnu, Sri Chinmoy (who gave the name of Mahavishnu to John, Miles Davies etc.

Savepost a comment