Graham Reid | | 4 min read

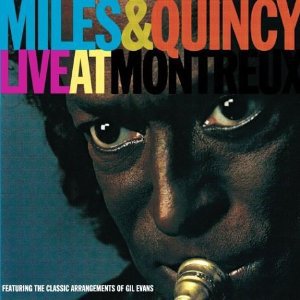

Miles Davis and Quincy Jones: Blues for Pablo

It was emblematic of the soul rebel

career of Miles Davis that in his final years he was painting as much

as he was playing, had a cameo spot in a movie (Dingo) playing a

pre-electric period jazz trumpeter, exchanging tapes with Prince,

recorded with rapper Eazy Mo Bee and – most surprising of all

turned up at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1991 to play some classic tunes

from his early years.

Davis always said he never looked back

- but he did, of course. Increasingly he spoke of his late Eighties

collaborations with Marcus Miller as being like those he did with Gil

Evans the Fifties. And after Evans' death in '88 Gil was much on

Miles’ mind.

Maybe that’s why he chose the 25th

Montreux Festival to revisit those tunes, as a nod to Gil from a man

who knew his time was coming close too.

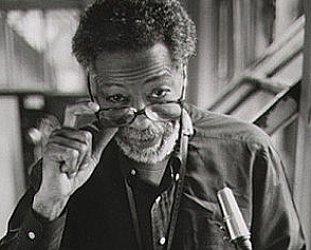

Certainly old friend Quincy Jones --

who had never shared a stage with Davis, surprisingly – was the

prompt and when Jones got the Evans charts, a great band together and

made things easy for Davis it was ll on.

Except for Davis who, typically, didn't

bother which such formalities as rehearsals (his dep was Wallace

Roney) and showed for just one run through.

The Davis-Evans music was great music -

it was fortysomething years ago and is now. That's a given . . . the

other thing we bring to this album is the knowledge that these were

among the last notes Davis blew. Ten weeks later he was dead.

The Davis-Evans music was great music -

it was fortysomething years ago and is now. That's a given . . . the

other thing we bring to this album is the knowledge that these were

among the last notes Davis blew. Ten weeks later he was dead.

So Live at Montreux comes with its own

weight of meaning.

Too often it is easy bow to music

because of who is making it, why it was made or peripheral matters

such as the health of artist.

Live at Montreux transcends all that

easily.

For the opener Davis and Jones reach

way back to the Birth of the Cool days in the late Forties with a

hesitant rendering of Boplicity. Davis is cautious, lets the

orchestration carry him. takes his first solo slowly then steadily

extends himself. By the end, and it's only about four minutes long,

he has found himself. From here on it is mostly assured - if fragile

-- Davis sitting within the rich, warm and supportive arrangements.

Very supportive, in fact.

Roney was at Davis' side ready to pick

up the task if necessary. It seems he wasn't, although on Miles Ahead

it is Roney who plays the solo, to be joined by Davis on only the

last chorus.

Once too often Jones pulls a brash,

brassy sound to the fore from the double-handling orchestra he has on

call (the eight-piece Gil Evans Orchestra with Miles Evans, Gil's son

on trumpet, and the massed George Gruntz Concert Band).

But the focus is on Davis all the way .

. . as it should be.

And he seldom disappoints despite the

occasional missed note which he always elevated to a stylistic device

anyway.

His first solo on Maids of Cadiz is

muted and recalls the pointillistic treatment he offered in the past

to Round Midnight, My Ship is delivered (deliberately) as if he has

barely enough life in him to essay the lovely Gershwin/Weill ballad

(his later solos have him in command) and Blues for Pablo at the

midpoint is deliciously engrossing.

Together Davis and Jones move through

the years in a Porgy and Bess acknowledgment.

Summertime finds Davis strutting coyly

in the taster tempo before letting altoist Kenny Garrett pile on the

pressure. The album bows out with two pieces from Sketches of Spain;

a short poke around in The Pan Piper which at less than two minutes

isn’t illustrative of very much and, much better, a reading of the

stately Solea where Davis engages in tightly coiled interplay with

Garrett. It is here too however where you can hear the loss of power

replaced by his idiosyncratic stylisations.

With a cast list which reads like a

Who’s Who of this music (Lew Soloff, George Adams, Jerry Bergonzi,

Grady Tate) there is plenty to be appreciated other than Davis here.

But this was -- and is – Davis’ show.

Quincy Jones says that Davis sometimes

smiled and even deliberately faced the audience, both rarities in the

last couple of decades of his career. Jones says Davis enjoyed

himself on these old tunes with which he'd made his name.

The event of Davis at Montreux imposes

a convenient, if artificial and unintentional, symmetry on a career in

modern music which was as tetchy, creative, unpredictable and revelatory as it was – that rarest of commodities, even in jazz –

unique.

post a comment