Graham Reid | | 5 min read

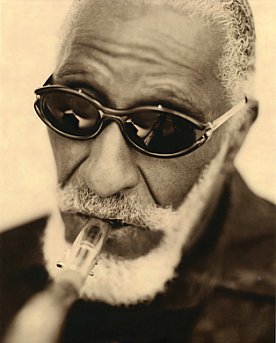

Gary Giddins, the authoritative US jazz critic, said of tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins that he was “one of the last immortals, the most powerful presence in jazz today. He is its most cunning, surprising and unpredictable improviser – the one musician whose infrequent concert appearances foster intense anticipation and heated postmortems.”

Giddins wrote that in 1996. Rollins – an old lion at 80 – is still at large, scheduled to play in Wellington in June, and is even now picking up accolades.

In 2001, he won a jazz Grammy for his album with the self-effacing title This Is What I Do, and three years later he was given a Lifetime Achievement award. In 2006, he won another Grammy for Why Was I Born? on his 9/11 tribute album Without a Song – recorded just five days after the World Trade Center fell – and the same year won three Downbeat magazine awards.

“I stayed alive long enough that they finally had to come around to me,” he says, laughing. “I say that because so many of my contemporaries were never really honoured properly. But I’m glad they honour me because they are honouring jazz, not me, and the great musicians I learnt from. So I accept them, they’re very tardy in recognising jazz.”

The New York jazz world in the 1950s wasn’t slow to acknowledge Theodore “Sonny” Rollins, however. In his late teens he played alongside pianist Bud Powell and by his mid-twenties – after 10 months in prison for armed robbery, and methadone treatment for a heroin habit – he took to bandstands with Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and other legends in the making.

His early albums – Saxophone Colossus (1954), A Night at the Village Vanguard (1957), Way Out West (also 1957, for which he played country melodies and posed on the cover dressed like a sharp-shooter) and the socio-political Freedom Suite (1958) – were so exceptional they have cast a shadow over his long career. Every subsequent album was inevitably measured against them.

But Rollins – generous, exceptionally modest and of quick humour – is charitable. “I feel gratified [about the recognition], as that period was something remarkable, but I don’t take that seriously, because I’m still involved in my art. I practise every day, still write music, but I understand some like that period and think everything else should be dependent on that. I’m still engaged in what I’m doing so I don’t pay much attention.”

However, the pressure early acclaim brought was so great that in 1959 he took three years off – the first of a few sabbaticals, equally a mark of his early career – and practised on the Williamsburg Bridge. Fending off playing opportunities, he went to clubs (“I was hearing John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman when he was playing in my neighbourhood”), but was aware of his technical limitations: “I would have probably stayed away another six months, but economics intervened.

“I was aware of my inner self so I was answering to that, not listening to my crowd or my fans. I had a strong sense I needed to improve and practise. That was one of my most impressive achievements. I’d like to be remembered as a person who followed his inner voice.”

Such time out – “People were telling me if I stayed away the public would forget me” – and the humour he brought to his music confused critics and audiences alike. “Some didn’t accept me as bona fide when they heard me being humorous.But in this world we have to have a sense of humour.”

Few serious, hard-bop musicians, however, would use How Are Things in Glocca Morra, I’ve Got You Under My Skin or There’s No Business Like Showbusiness as vehicles for improvisation. Way Out West may have surprised critics with its versions of Wagon Wheels and I’m an Old Cowhand, but as a kid Rollins had loved Tom Mix two-reeler Westerns, so why wouldn’t he play these tunes?

“Probably they didn’t understand why as a jazz artist I was doing that. People didn’t know how to – and probably still don’t – accept me because my career doesn’t go from A to B to C. I’m very eclectic, not what people expect.

Rollins certainly didn’t play the same thing all the time in the 1960s, when his music sometimes seemed directionless and his appearance would change regularly. He even sported a Mohawk.

“[That time] was growth in all directions; I never label myself or am closed to anything I might hear and like. The essence of jazz is being a free spirit. I’m a free spirit, a primitive really. I don’t feel I should be bound by any set of rules – and jazz gives me the opportunity to be like this.”

Most critics have agreed Rollins was seldom at his best in the recording studio: “That’s probably true, because the way I play is more spontaneous. Live performance is the optimum, in the moment on the bandstand.”

“People would say Coltrane plays in a mathematical way which is easier to emulate, Sonny plays in a much more disjointed way,” he says, laughing. “So I’m not easy to emulate because what I do is changing all the time. The style is not easily captured.”

Ironically, many might be most familiar with this jazz giant’s playing from a Rolling Stones album, their Tattoo You from 1981. Rollins appeared uncredited on a few tracks, notably the ballad Waiting on a Friend. “It wasn’t my idea, it was my wife’s. So I went down to see how it would turn out and whether the styles could meld.”

That they did is a measure of Rollins’s openness to other idioms, although he admits he hasn’t listened to much music in the past two decades: “I listen to sports radio. I don’t want to get a lot more [musical] information, I want to be my own voice.”

He still receives excellent live reviews and for his Wellington show brings bassist Bob Cranshaw – with whom he has played for almost 50 years – and hot players half his age. He laughs loudly when asked if he might play Waiting on a Friend. He might drop in a quick quote, if he’s feeling mischievous.

“I don’t know what I’m going to play. That makes it wonderful for me because there’s no end to what I’m doing, there’s always the search. It can just go on.”

post a comment