Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Miles Davis: Splatch

.jpg)

Depending on when he was talking and

the mood he was in, Miles Davis would claim to have changed the

direction of music three – or four – times. No one would doubt

the impact of Birth of the Cool, Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew –

which might make the “three”.

But the fourth?

Although it didn't change the course of

music as he might have wanted to believe, there is a case that his

controversial '86 album Tutu changed his own direction, albeit rather

briefly. It certainly was one in the eye for George Butler at his

longtime label CBS because . . .

Maybe Butler, the head honcho at CBS

Records – as Sony used to be -- regretted making that phone call to

Miles Davis. Then again, maybe he didn't.

When Butler rang Davis in the mid Eighties and suggested Davis phone their hot new signing, jazz trumpeter Wynton

Marsalis, to wish him happy birthday, Davis was furious. They'd

already delayed releasing his Time After Time album and wouldn't pay

for a tribute album so Davis had had to dig into his own money from

an endowment . . . and now this insult.

Ring the guy who was replicating Davis'

former style and saying derogatory things about his new music?

“I knew right then I had to get away

from those [Oedipal cussword] at CBS. That was the only way they

could get some publicity for Wynton,” he told me in '88.

So Davis quit his record company of 30

years – to whom he had delivered milestone albums such as Porgy and

Bess (in 1958), Kind of Blue ('59), Sketches of Spain ('60), In a

Silent Way ('69) and Bitches Brew ('70) – and moved on.

In truth though, Butler may not have

been unhappy to see him go. Davis' street-funk and rock-influenced

albums of the Seventies – On the Corner, Get Up With It, Star

People, You're Under Arrest – and his most recent live set We Want

Miles (with guitarist Mike Stern grabbing space) hadn't set useful

sales figures. They'd also alienated Davis' jazz following without

bringing in the funk and rock crowd.

And Davis was never easy. He'd been

scathing about Marsalis, plagued with drug problems again and at any

opportunity would point out the racism he saw in the music industry.

And Davis was never easy. He'd been

scathing about Marsalis, plagued with drug problems again and at any

opportunity would point out the racism he saw in the music industry.

Which might be why his first album for

his new company Warners was Tutu, after Archbishop Desmond Tutu of

South Africa. And why headed in another new direction.

It was the centre of the

synth-splattered Eighties – the previous years had seen Prince's

Purple Rain, Madonna's Like a Virgin and the rise of bands like

Wham!, Tears for Fears and Scritti Politti – and Davis was keen to

work with Prince.

But, as with his plan to work with

Hendrix just before the guitarist's death, things fell through. So he

hooked up with bassist/multi-instrumentalist Marcus Miller who had

spent much of his career as a sideman (briefly with Davis), session

player and arranger.

Miller was the guiding hand behind

Tutu. Of the eight tracks he wrote all but two (one a co-write with

Davis) – the others were George Duke's Backyard Ritual and Scritti

Politti's Perfect Way. He also co-produced it with Tommy LiPuma (who

had signed Davis to Warners with some trepidation).

Miller was the guiding hand behind

Tutu. Of the eight tracks he wrote all but two (one a co-write with

Davis) – the others were George Duke's Backyard Ritual and Scritti

Politti's Perfect Way. He also co-produced it with Tommy LiPuma (who

had signed Davis to Warners with some trepidation).

Miller handled most of the instruments

– synths, sequencers and drum machines which gave a staccato feel

to the r'n'b funk – and when the album was released many critics

savaged it saying Davis had been hijacked by Miller's synth-funk

sound.

As if Davis could be made to do

anything he didn't want to do?

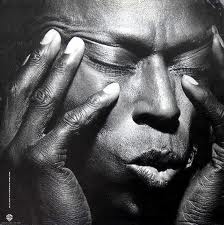

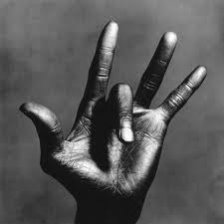

Tutu – in striking cover photos by

Irving Penn -- stands as a late career high for Davis who immersed

himself in the bed of synth sounds and also, although this was often

overlooked at the time, played some fine solo work throughout. He was

tight and pointed, never flashy and always working within the service

of beats and grooves.

He worked again with Miller on the

soundtrack to the film Siesta the following year – a sort of lesser

version of a synth-funk Sketches of Spain if you can imagine that –

but by this time Davis was just doing one-off projects (the

inevitable hip-hop album wasn't to far off) so Tutu was to be his

last innovative hurrah.

He worked again with Miller on the

soundtrack to the film Siesta the following year – a sort of lesser

version of a synth-funk Sketches of Spain if you can imagine that –

but by this time Davis was just doing one-off projects (the

inevitable hip-hop album wasn't to far off) so Tutu was to be his

last innovative hurrah.

But it didn't change the direction of

music.

Tutu is now re-presented in a

remastered 25th anniversary edition with an extra disc of a concert

in Nice that year with a brittle funk-rock band – which includes

saxophonist Bob Berg, guitarist Robben Ford and two synth players –

stretching out on older material (Jack Johnson), pieces from Tutu

(Portia, Splatch) and contemporary pop hits Human Nature (Michael

Jackson) and Time After Time (Cyndi Lauper).

Those who found Tutu a step too far

from jazz won't warm to the extra disc which is often more akin to

rock – like We Want Miles with a synth-funk edge – than even the

constrained playing on Tutu.

But Tutu was a fine late-period Davis album and open ears at the time accepted it as Davis pushing in a new direction, and some of its critics found themselves warming to it over time.

Within a year it was being hailed as Davis' comeback album

and scored him another Grammy, for best jazz instrumental performance.

It also became one of Davis' biggest

selling albums.

You wonder if he called George over at

CBS to tell him.

post a comment