Graham Reid | | 3 min read

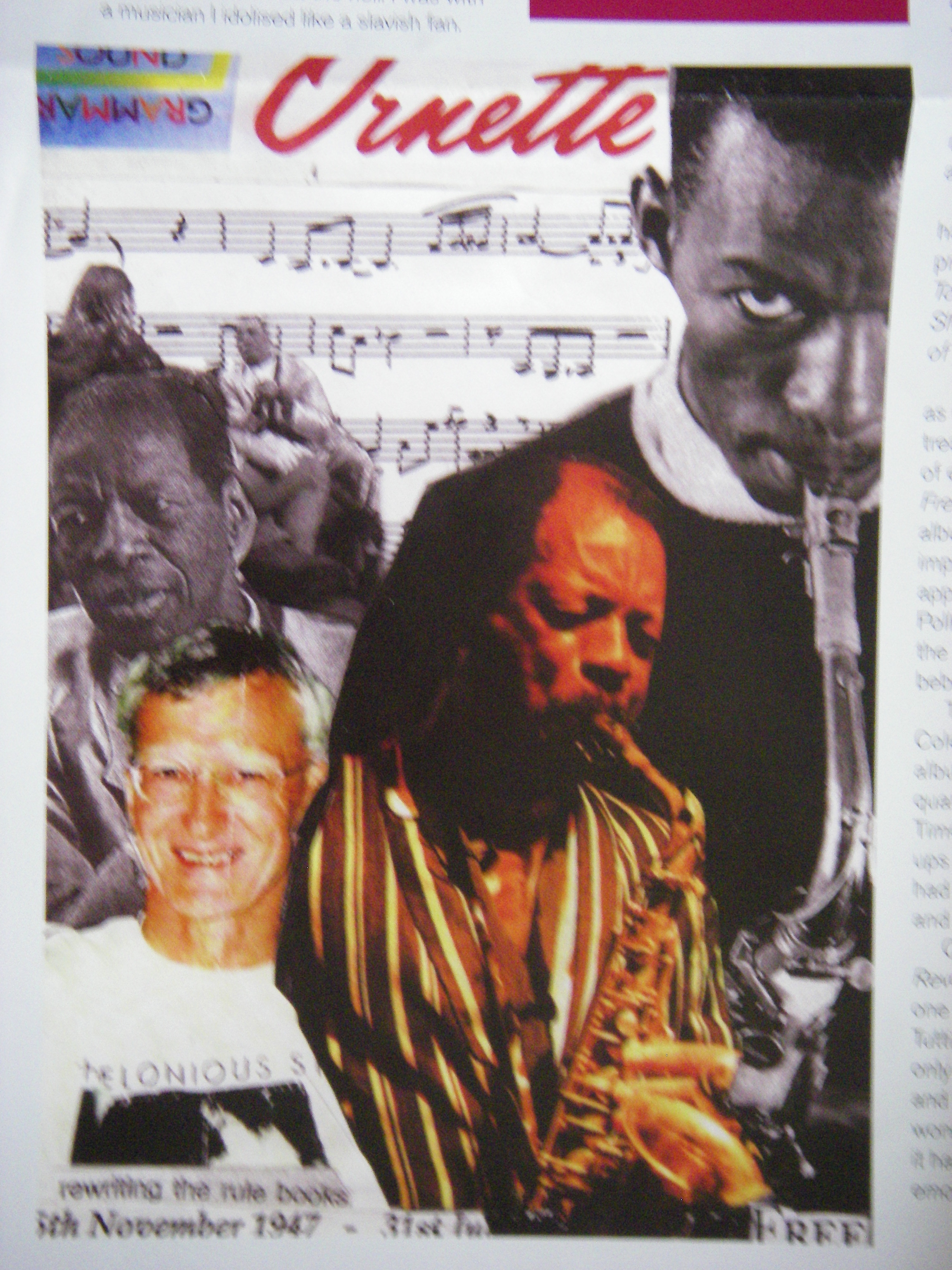

I thought I knew all about Ornette Coleman, a man nominally described as a jazz musician but among the most unconstrained musical geniuses of the 20th century. I’ve got a couple of dozen Coleman albums on vinyl and at least that many CDs. I’ve got bootlegs and biographies, and a photo of Ornette and me on a couch in a New York loft taken when I interviewed him in ‘96.

Coleman was eccentric and if his conversation was sometimes impenetrable . . . what the hell. I was with a musician I idolised like a slavish fan.

So yes, I thought I knew my Ornette -- until I recently picked up a double disc of two concerts on his 1968 Italian tour. And until then I never knew Coleman had played shenai, an Indian instrument like a rough alto sax.

But here he is, blasting away on this appallingly entitled set, The Love Revolution (Gambit Records). It was a revelation.

But Coleman’s career always, for each new generation discovering him, has the capacity to surprise.

Saxophonist Coleman came out Fort Worth in the late 40s and learned to play in that tough Texas blues style. He was largely self-taught, and then un-taught himself as he looked for new ways to develop his music. In the mid 60s he recorded with his 12-year old son Denardo on drums.

“Unadulterated shit,” said drummer Shelly Manne. Trumpeter Freddie Hubbard observed the obvious: Denardo sounded “like a little kid fooling around”.

Criticisms hardly worried Coleman: he’d had more than a decade of them by then. He’d been literally punched, and frequently threatened by musicians who didn’t understand his angular approach to melody, or simply thought he was taking the piss. Miles Davis considered Coleman’s trumpet playing insulting to trumpeters. Violinists hold a similar opinion of his atonal scrapings.

A decade after he washed up in California in the early 50s Coleman worked odd jobs; was ridiculed for playing a white plastic alto (bought when he couldn’t afford a proper sax); and couldn’t get work because musicians were bewildering by his approach to melody and time.

By the late 50s however Coleman had released remarkable albums with prophetic titles: Something Else!!!!; Tomorrow is the Question; The Shape of Jazz to Come; and Change of the Century.

Then the man who spoke of music as colours and architecture -- and treated melody and rhythm as being of equal importance -- unleashed Free Jazz, a revolutionary double album which featured two quartets improvising simultaneously. In a cover appropriately featuring a Jackson Pollock abstract, Free Jazz ushered in the 60s and liberated the music from bebop changes.

There was no looking back for Coleman and what followed were albums with orchestras and string quartets, his electric band Prime Time, unusual trio and quartet line-ups (on that Italian tour in 68 he had two bassist and a drummer), and much more.

On the exceptional Love Revolution -- where every track except one reaches beyond 10 minutes, and Tutti is an engrossing 23 -- Coleman only hauls out shenai for the funky and squirreling Buddha Blues. You wonder why he didn’t explore it more: it has an astringent tone that suits his emotionally affecting music.

But I guess Ornette was moving on: a fortnight later he was at the Royal Albert Hall with Yoko Ono in screaming mode. .jpg)

Coleman, now 76, has played with the Master Musicians of Joujouka, the London Symphony Orchestra, and the late Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead (on an approachable album called Virgin Beauty). Among his uber-fans are guitarist Pat Metheny and John Zorn. In the mid 60s he did the soundtrack for the film Chappaqua Suite (dropped by director Conrad Rooks who felt it too beautiful and would overwhelm the film) and 30 years later did the unnerving soundtrack to Naked Lunch.

Coleman unleashed shards-of-sound guitarist James Blood Ulmer on an unsuspecting world, and works with his self-devised “harmolodic theory” which perhaps only he and three others fully understand.

He’s a genius, was only the second jazz musician to win a Pulitzer Prize for music, and was recently awarded a Grammy for Lifetime Achievement. (He made a typically incomprehensible speech on accepting it.)

He has a new album out, Sound Grammar (Sound Grammar Music), which also won a Grammy. Everywhere on it Coleman (still undeterred on sax, violin and trumpet) is endlessly, relentlessly and brilliantly melodic -- and the line-up is a drummer (son Denardo again) and two bassists, just as he had in Italy almost four decades ago.

There’s an appealing circularity and symmetry between Love Revolution and Sound Grammar, both live recordings, which confirm the consistency of Coleman’s idiosyncratic vision.

Ornette Coleman is -- and I say this as one who thought he knew it all -- a constant (re)discovery.

post a comment