Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Don Cherry Quintet w Pharoah Sanders: Cocktail Piece (take 2)

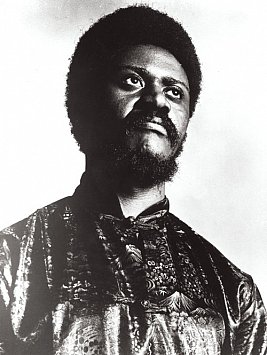

The two times I saw the great Pharoah Sanders he could not have played more differently: the gig in a New York club had him as the edgy post-bop player in front of small, serious audience; the performance in New Orleans as a populist Afro-funk soul-inspired jazzman who had people up and moving.

I interviewed him in 2004 in advance of an Auckland concert (which I didn't see because I was overseas, and it was apparently poorly attended) and it was a painful experience. Perhaps as much for him as me. He spoke in clipped and distracted responses.

At those two concerts however – even the one in New York which pushed at boundaries – it was hard to imagine this distinguished, white-bearded man in colourful clothes as the revolutionary free jazz figure he was in the early Sixties when – along with Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Eric Dolphy, Archie Shepp, Don Cherry, Paul Bley and others – he reshaped the coordinates of jazz in the pursuit of individual expression.

Now in his early 70s, Sanders is one of the few still standing of that remarkable generation. Coleman, Taylor and Bley are still out there of course (appearing sparingly however), but it is Sanders who has most often used the innovations of John Coltrane's later career as his starting point to uniquely shape his individual expression.

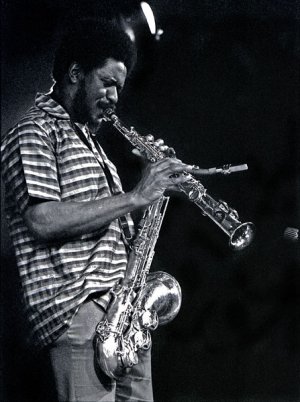

Born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1940, the saxophonist arrived in New York in 1961 and by the middle of the decade had established his reputation as a member of Sun Ra's Arkestra, and also playing in groups lead by trumpeter Cherry and pianist Bley.

Schooled in rhythm and blues, and having been a drummer, he was initially influenced by Sonny Rollins while working in California then had embraced the more avant-garde stylings of Coleman, Coltrane and Dolphy.

It is said that Coltrane moved further out after having seen Dolphy play, and it was at that time – in '65 – that Sanders joined his final group and appeared on the exceptional Ascension album.

After Coltrane's death in '67, Sanders just kept pushing further and further.

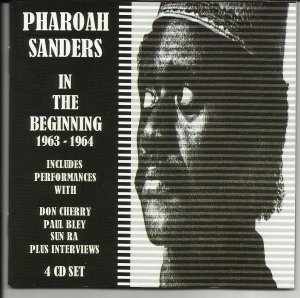

But an impressive four CD set on the

ESP-Disk label Pharoah Sanders: In the Beginning 1963-1964 captures

him as he was making his first serious moves from rhythm and blues

into more free playing.

But an impressive four CD set on the

ESP-Disk label Pharoah Sanders: In the Beginning 1963-1964 captures

him as he was making his first serious moves from rhythm and blues

into more free playing.

Across these discs – which include interview snippets – we hear Sanders playing in the quartets of Bley and Cherry, as well as lengthy live recordings with Sun Ra and His Solar Arkestra, and with his own quintet in '64.

At this time Sanders was broke, living dirt cheap and at one point has his saxophone in hock. The pieces with Cherry (a longtime Coleman offsider), pianist Scianni, bassist David Izenzon (soon to join Coleman) and drummer J.C. Moses are clearly influenced by Coleman, especially the second take of Cocktail Piece where Cherry and Sanders play the airy melodic line before things devolve into musically strident and atonal passages.

It is the sound of young men full of confidence pushing their way into this new music, yet Sanders' tenor also retains a romantic quality in the more ballad-like section.

The four minute Cherry's Dilemma is a much more fragmented and daring piece, the players running on parallel tracks and Scianni all over the keyboard with melodic energy.

A hallmark of this disc is how melodic the playing can be (Cherry's Remembrance), the influence of Coleman (there are snippets of Cherry speaking about exactly that) and the short working through of some Thelonious Monk tunes by Cherry on piano in a studio rehearsal-cum-medley.

Canadian Bley talks about how piano was being sidelined (Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker and Coleman's groups) and how he tried to play near the original note to get the instrument back into the free jazz game and how the players he liked best came from the tradition but “matured into the free jazz freedom”.

The two pieces of Sanders with Bley's quartet (Izenzon and drummer Paul Motian) and their alternate takes – Generous 1 and Walking Woman – have the saxophonist in some seriously skittish but melodic playing and he sounds assured, especially in the second take of Generous 1 where he and Bley trade ideas and attitudes as much as melodic constructions.

When he appears on the second disc with

his own Quintet he admits he was still picking up ideas from the

milieu of New York musicians.

When he appears on the second disc with

his own Quintet he admits he was still picking up ideas from the

milieu of New York musicians.

ESP-Disk boss Bernard Stollman interviewed recently says he doesn't know how why he recorded him in '64 (“he was very surly, hostile, brusque, not friendly”) but he was glad he did: “They did their sessions, got their money and split and I haven't seen or talked with him since”.

The two tracks Seven By Seven and Bethera (both over 20 minutes, with Stan Foster on trumpet, Jane Getz piano, William Bennett bass and Marvin Pattillo drums) are firmly in the post-bop idiom with little of the “outside” playing Sanders came to adopt after playing with Coltrane some years later.

But there are substantial sections where he pushes hard and far into atonality, squealing and abrupt stops.

The shape of jazz to come from Pharoah.

Perhaps of greatest interest to current listeners are the two discs of Sanders with Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra at Judson Hall in New York.

The mystique of Sun Ra has carried further into the wider consciousness than that of Sanders, and here is a fine line-up in the band which includes trumpeter Al Evans, trombonist Teddy Nance and Marshall Allen on alto.

This is also highly approachable music in that Ra's style at the time was evocative and constructed in short suites (Dawn Over Israel, The Second Stop is Jupiter, Gods on Safari etc). Ra came from a tradition which Sanders knew and respected. Closer to art-jazz (cf. art-rock with percussion solos) than free jazz as many understand, or misunderstand, it.

Within a year of these recordings, Pharoah Sanders had joined Coltrane's group and rather than being influenced by the master, he brought his own ideas of free playing which Coltrane assimilated and turned into something his own. Sanders in turn imbued his sound with a more overtly spiritual elements as a result of their association, recorded on Impulse! and subsequently worked with Alice Coltrane . . . and became the name player and grand master we know today.

But these early years in New York were formative and even though some of the pieces on this four CD set are snippets (especially those with Cherry, then Bley), they make for an interesting collection from one of the few remaining jazz giants of his generation, and through the interviews usefully recontextualise back into its period.

And also not a bad intro to Sun Ra for some.

For a better understanding of free jazz have a look at the DVD doco Inside Out in the Open.

post a comment