Graham Reid | | 4 min read

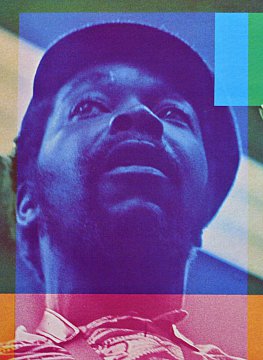

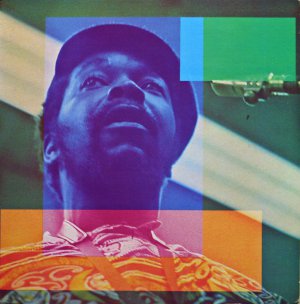

Marzette Watts and Company: Geno

Should anyone doubt the close connection between American free jazz and the rise of radical black politics in the Sixties they only need to look to the life of saxophonist Marzette Watts.

However Watts -- who died in early '98 a week short of his 50th birthday -- gets barely a footnote in any jazz histories. His name is usually just as part of a list which includes Ornette Coleman, Marion Brown, Henry Grimes and so on. Even his friend , the poet/writer and activist Le Roi Jones (Amiri Baraka) didn't mention him in his 1967 book of essays Black Music.

At the time Watts was recording for Bernard Stollman's fledgling ESP-Disk and laid down his album in one day in late '66.

Most consider the free jazz/revolutionary politics junction to have arrived in the mid to late Sixties, notably with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, New York's Revolutionary Ensemble, and players such as Archie Shepp, Cecil Tayor, Albert Ayler and others.

But Watts -- from Montgomery, Alabama -- was attuned to black politics, identification and activism from an early age. In college in his late teens he was a founding member of the SNCC (Students Non-Violent Coordinating Committee which morphed into a more vigorous form of activism under Stokely Carmichael) which put him in the vanguard of the civil rights movement shortly after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on that Montgomery bus and Martin Luther King-lead the bus boycott.

In 1960 Watts -- not yet a musician although he had played a little piano -- moved to New York, lived in the same building as Jones/Baraka with whom he founded the Organization of Young Men, then moved to Paris in '62 to study painting at the Sorbonne (later in the decade the centre of French revolutionary student movements) where he started playing sax to earn some ready cash.

Quite when Watts began to take the music more seriously -- when he returned to New York a year later he was still determined to be a painter -- is unclear. But he certainly began studying under trumpeter Don Cherry and jammed with those in the frontline of the free jazz movement like bassist Henry Grimes and drummer J.C Moses (Both of whom appear on his self-titled ESP-Disk album).

His New York loft become a focal point for the likes of Coleman (by then broke and finding it hard to get work despite his innovative albums), Cecil Taylor, Cherry, Shepp and Pharoah Sanders.

Given that illustrious company it seems increasingly strange that Watts so should be so marginalised and overlooked today.

Given that illustrious company it seems increasingly strange that Watts so should be so marginalised and overlooked today.

But even at this time he was still looking to a career in painting and it wasn't until '65 when -- after disillusionment with the art world which rejected his abstract expressionism and skin colour -- that he turned to saxophone more seriously, relocated to Denmark to study, then came back to New York to record that album for ESP-Disk, which has now been given a long overdue reissue.

The album session had -- alongside Watts on tenor, soprano and bass clarinet, Grimes and Moses -- Byard Lancaster (alto, flute, bass clarinet), guitarist Sonny Sharrock, Clifford Thompson (trombone, cornet), bassist Juni Booth and vibes player Karl Berger.

Astute observers will note the paralleling to some extent of Ornette Coleman's double-quintet line-up from Free Jazz, but also the inclusion of Sharrock, an incendiary player whose staccato firepower would go on to become a cornerstone of many free jazz albums.

That black politics was in the forefront of Watts' thinking is evidenced by the 20 minute Backdrop for Urban Revolution, an occasionally explosive piece -- especially when Sharrock starts tossing out shards of sounds which sound like storefront windows breaking.

Jazz at this time -- free jazz that is -- was four years on from Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln's We Insist: The Freedom Now Suite which came in a cover showing a sit-in at a segregated Southern lunch counter.

Around this time Archie Shepp said, "Some of us are more bitter about the way things are going. We are only an extension of that entire civil rights-Black Muslim nationalist movement that is taking place in America. That is fundamental to music".

Malcolm X frequently spoke of the black jazz musician's ability to improvise as analogous to his ability to think laterally in politics. In mid '64 he said, "The white musician can jam if he's got some sheet music in front of him. He can jam on somethng that he's heard jammed before. But that black musician, he picks up his horn and starts blowing some sounds that he never thought of before. He improvises, he creates, it comes from within.

"It's soul; it's that soul music. It's the only area on the American scene where the black man has been free to create. And he has mastered it."

It's worth noting however that most free and mainstream jazz musicians might not have made such a color demarcation. Most bands were integrated, and Watts had German-born Berger in his band for this album.

In his collection Cats of Any Colour the critic Gene Lees addresses the race issue in the essay Jazz Black and White and cites any number of black artists dismissing colour as a dividing line.

But this music was about black identity because that was the tenor of the times and the issue facing those -- black and white -- who were making it.

But this music was about black identity because that was the tenor of the times and the issue facing those -- black and white -- who were making it.

Three days before he was assassinated in February '65, Malcolm X told students at Columbia, "We are living in an era of revolution, and the revolt of the American Negro is part of the rebellion against the oppression and colonialism which has characterised this era . . ."

The time was right for violent revolution . . . This was the Backdrop for Urban Revolution.

That is the world in whch Watts and Company -- as they were credited on the cover -- created his sole album for ESP-Disk. And after that he moved briefly to Savoy although much of it went unreleased for a decade.

By that time Watts had moved into teaching at universities in the US and Europe, and finally ended up in Nashville where he died of heart failure.

His legacy is small, but significant. As much for what it says in musical terms as it tells about the era in which it was created.

And that is why we need to talk about Marzette Watts.

For other articles in the series of strange or different characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

For more on free jazz on the ESP-Disk label see here, and this general overview of free jazz/black politics.

Graham - Apr 29, 2019

I can't immediately see where to get the re-release - any clues?

Savepost a comment