Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Special Edition: Riff Raff

If you got togther any group of contemporary jazz drummers -- "a violence of drummers" perhaps? -- it would be the rare figure in their midst who didn't name Jack DeJohnette among their top five influences.

Born in August 1942, DeJohnette has enjoyed a career which spanned what was called the avant-garde (with Roscoe Mitchell, Richard Abrams and others in his hometown of Chicago), playing with the enormously popular Charles Lloyd, the great Bill Evans and then Miles Davis (on hand for Bitches Brew, Jack Johnson, On the Corner among other sessions). Most of that before he was 30.

And, from the early Seventies, he was on the ECM roster and has played with most of the key American musicians on the label, notably Keith Jarrett whom he'd met in Lloyd's band and still plays with today, and some of the Europeans.

Two years ago in an interview with Elsewhere (here), we joked about him being that rarity, he'd played on a hit jazz album (Forest Flower of '68 with the Lloyd group which caught the late Sixties hippie/world music vibe).

"That's right,” he laughed as he recalled those vibrant days. “The Charles Lloyd Quartet preceded Miles at the Fillmore. It was quite a time: Sly and the Family Stone, bands like Blood Sweat and Tears, and Chicago. It was very fertile time for experimentation, the Beatles were big and Ravi Shankar had introduced Indian music to American audience at festivals. There was a lot of cross-pollination in music, and jazz too.”

DeJohnette was always open to the cross-pollination of ideas. He played in rhythm and blues bands, worked in hard bop and fusion, could play restrained for some of the more delicate ECM outings and latterly has explored New Age music (for which he won a Grammy).

And that open mindedness is what he brings when he sits behind a kit: he can draw from a long history of jazz -- from formal to free -- but has also had his ears on classical and world music, and can change a tune just by subtle shifts of emphasis, or creating an almost abstract substructure behind the bassist and saxophonists . . . the line-ups he most commonly works with.

Once settled at ECM he started to push those ideas and influences onto a series of excellent albums which began after his '78 New Directions (the title something of a misnomer despite the promising presence of guitarist John Abercrombie, trumpeter Lester Bowie and bassist Eddie Gomez).

Things really took off the following year when he launched his own band name: Special Edition.

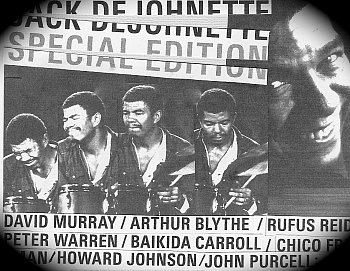

The flexible group line-up -- only DeJohnette a constant on subsequent recordings -- announced itself with the self-titled album in early '79 which had saxophonists David Murray and Arthur Blythe alongside bassist/cellist Peter Warren. It was an unusual configuration but Murray and Blythe had much in common despite Murray being an emerging force, with Blythe extending himself in such company.

Blythe's tough'n'tender tone saw him signed to Columbia around this time for albums which are worth seeking out even now, notably Lenox Avenue Breakdown and Illusions which featured tuba player Bob Stewart. If they sound a little tame, they are also highly enjoyable.

With Special Edition's debut this group explored DeJohnette originals and Coltrane's India (giving it a delicate reading). It was an astute choice, it was a piece which reminded people who'd thought of the drummer in the context of Miles Davis' fusion and funk albums that he'd also been in the Coltrane Quintet, another unique configuration which had seen him alongside fellow drummer Rashied Ali.

It is an exceptional album and something of a signpost to what would follow under the brief DeJohnette/Special Edition imprimatur in the first half of the Eighties.

DeJohnette's four studio albums as Special Edition from this period have been repackaged by ECM into a handsome little box, and it also offers that rarity on the label, an excellent background liner essay in the 36 page booklet.

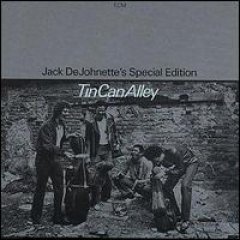

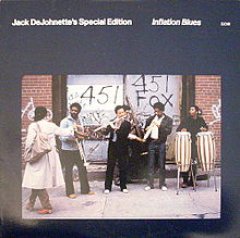

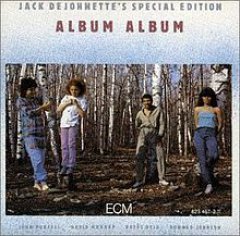

The box includes that debut; Tin Can Alley from '81 (with saxophonists Chico Freeman and John Purcell, bassist Warren back); Inflation Blues of '83 (Freeman, Purcell, bassist Rufus Reid and guest trumpeter Baikida Carroll on a few tracks) and Album Album from '84 (Murray, Purcell, Reid and tuba player Howard Johnson).

The box includes that debut; Tin Can Alley from '81 (with saxophonists Chico Freeman and John Purcell, bassist Warren back); Inflation Blues of '83 (Freeman, Purcell, bassist Rufus Reid and guest trumpeter Baikida Carroll on a few tracks) and Album Album from '84 (Murray, Purcell, Reid and tuba player Howard Johnson).

It's a shame the original album covers weren't reproduced larger in the booklet because they also said something about the period under Ronald Reagan's presidency, but the music is enough.

(For your information here they are, right, and every picture tells a story.)

Inflation Blues is a standout album, although the title track which gets between reggae and funk with DeJohnette's thin vocals on a complaint about Uncle Sam the Taxman, unions and the struggle to survive won't be to every taste.

Inflation Blues is a standout album, although the title track which gets between reggae and funk with DeJohnette's thin vocals on a complaint about Uncle Sam the Taxman, unions and the struggle to survive won't be to every taste.

(Certainly isn't to mine, he writes lyrics as cliches without nuance).

But elsewhere on the album are the opener Starburst which sounds like it might be chamber music from a loft before getting seriously edgy, the stately Ebony where dark bass clarinet and high flute are astutely played off against each other, and Slowdown takes a more liberated approach to improvisation.

Listening across these four albums you cannot help be struck by the sheer volume and weight of musical ideas Special Edition, in its morphing forms, managed to explore with such conspicuous success.

Listening across these four albums you cannot help be struck by the sheer volume and weight of musical ideas Special Edition, in its morphing forms, managed to explore with such conspicuous success.

The five minute Gri Gri Man on Tin Can Alley is the closest anything on these albums come to a "drum solo" but it is eerie . . . as it should be.

Yet the 15 minute ballad Pastel Rhapsody with DeJohnette on piano is understated and beautiful.

And Album Album benefits from the often weird and contradictory sounds of Purcell's soprano. He adopts a suitably Middle Eastern melodic sensibility on the opener Ahmed the Terrible where his voicing is offset against Reid's bass guitar and DeJohnette again on piano, the instrument this exceptional drummer learned first.

Which might explain his melodic approach to the kit?

When risks are take not everything works, of course. That's in the contract of improvised music.

But amidst the boundary-pushing they could still -- as on Monk's Mood on Album Album -- go back to sources and find something new to say.

That said, it's rather hard to hear some of this out-there music -- some of referenced in jazz's illustrious past, and also in DeJohnette's own even though he was just 40 when these recordings were made -- and not think . . . Jeez, this guy went on to win a Grammy for a New Age album?

No one could have predicted that in the early Eighties when something called "New Age Music" was barely a concept . . . let alone something you'd cross the street to avoid.

A "violence of drummers" might have something to say about that.

post a comment