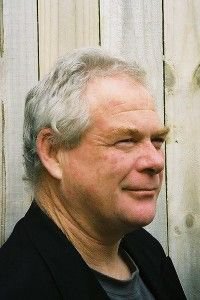

Graham Reid | | 9 min read

The plan would have been timely: a concert acknowledging the half century he’d known and played in bands with drummer Frank Gibson. But then everything changed. “They gave me a year, that was a year ago,” said 66-year-old keyboard player and composer McNabb about the cancer diagnosis he received. “So I’m going downhill gradually, losing weight. It’s getting hard to eat and I had a heart op in 2004, so it’s putting a strain on that. So I’m on the way out, but we’re all on the way out in one way or another. It’s just happening at a different time for me.”

That time came on Sunday, a little over a fortnight after this final interview in McNabb’s Auckland home.

Philosophical, still recording (two tracks for a duets album under Gibson, and recently the Anti-Borneo Magic double album with the astral-rock group Salon Kingsadore), McNabb was one of this country’s best, most heard but least known musicians.

With Murray Grindlay, he played on, wrote or arranged literally hundreds of commercials that have imprinted themselves in our collective consciousness – Mainland cheese, that famous Crunchie ad on the train, McDonald’s, John Grenell’s Welcome to my World Toyota ad . . . There were also songs like Sailing Away and the Red Nose Day theme, but as importantly the soundtrack to the television series Greenstone and the incidental music to Once Were Warriors.

It’s likely every person in this country has heard at least one, if not a dozen, songs that have McNabb’s fingerprint on them.

But that’s only a small measure of what McNabb – also an accomplished artist whose work appeared on a number of album covers – achieved.

“I had absolutely no compunction about selling myself to the advertising world,” he said, laughing. “I do them so I can make jazz records. I’ve really enjoyed making commercials. The only thing better is playing live music in an improvised situation. Apart from that, commercials and soundtracks are where it’s at for me.”

McNabb grew up in Auckland tinkering on piano as a child, almost entirely self-taught or with a few pointers from family members, and laughed about a music teacher giving up on him because he’d just memorise the music and not learn to read it.

Written notes, he said, in the spirit of the true improviser, “are only a memory guide, anyway”.

At Mt Albert Grammar, McNabb met Gibson, by then already established as a drummer, and the two discovered their mutual love of jazz.

“When I was at Grammar, I was walking around the quadrangle one day and I saw ‘Monk’ written on one of the brick walls,” says Gibson, referring to the name of jazz pianist Thelonious Monk, “and I thought, ‘Who the hell would write that?’ So I kept asking and someone said, ‘That was Murray McNabb’, and that’s how I met him. We started playing duets together, because we couldn’t find a bass player in 1963, in an old disused science lab that had an upright piano. I brought a set of drums to school and left them there.”

Unlike jazz players today, who can study a course in school or university, they learned by listening and playing, and went on a journey of discovery together that took them through award-winning and popular groups such as Dr Tree and Space Case.

Along the way, McNabb played in the pop-rock covers band Rainbow (“just chasing the hit parade and keeping up with the top 10”) and spent years in a country-rock outfit (“that was our starting point, it got a bit warped after that”), but jazz was always there, right from the day when one lunchtime in the late 60s he and Gibson auditioned for a six-night-a-week residency at Auckland’s Troika restaurant, and got it.

McNabb went back to George Walker’s auction house, where he’d been training as an accountant, and handed in his notice. The appeal of jazz was simple: “Freeeedom.”

“I was getting more than in the accountants’ office, the money was much better than now in comparison.”

His and Gibson’s subsequent careers took them through bars, clubs, restaurant residencies – often just changing the time signatures on standards to keep it interesting for themselves.

Gibson: “Even when we were in [restaurant] bands, we’d play our own versions of the standards and we’d get fired. We didn’t learn the arrangements of the other musicians; we didn’t learn them because we were more interested in our own way of playing. Most musicians today teach more than they play. In our era, we always played more than we taught.”

McNabb: “I don’t think it matters about these jazz schools; Frank knows I hate jazz schools, the idea you can get a degree in jazz just makes me want to puke. If you are going to be a musician, you will be a musician; the others will try for a while then do something else, probably teaching, which is the unfortunate part because you’ve got people teaching who never actually did it.

“And I mean really did it, and that’s more than just knowing where to put your fingers and how to pass an exam, it’s got to do with feeling and who you are as a person. But now there are no jobs on bandstands and in the studio to harden them up. There’s none of that, so what are these kids going to do? They’ve created this self-perpetuating cycle of people learning how to teach people who will go and teach, before they’ve even done it.”

Gibson: “If they ever do it.”

Inevitably, McNabb and Gibson formed their own groups of like-minded players, notably the popular and successful Dr Tree and Space Case in the 70s and beyond.

Dr Tree’s time-changing and experimental jazz-rock not only caught the spirit of the fusion era but scored them two wins in the New Zealand Music Awards in the late 70s, ironically both in the rock category.

“There wasn’t much happening in the rock business,” McNabb joked as he recalled being at the award ceremony. “I was sitting at the table with my hair down to here and there’s all these people coming round I didn’t know and saying, ‘We’ll be in touch.’

“And I never heard anything from anybody. But then I figured maybe I wasn’t a particularly ‘commercially acceptable’ person.”

“Murray’s philosophy and mine about having a group,” says Gibson, “was you find a residency and then try to get recorded. It took until 1976 to get it recorded by EMI in Wellington and they put out a run of 500 vinyls and they sold so quickly I said they should put out another 500, but they didn’t.

“We actively went out to look for gigs and found the Globe Hotel in Auckland with nothing happening on the top floor. So we did it all ourselves: we made our own bandstand and did the publicity. People just came and loved it because it was new. We played every Monday at the Globe for months and it was absolutely packed every time.”

Gibson notes that during Dr Tree’s four-year period, until he left for London in 1977, the band also had numerous visiting international musicians sit in with them, some of whom appeared as guests on the Space Case albums in the 80s when he returned to the country.

“When you’re in New Zealand,” says Gibson, “you think you’re not that good because we’re a small country. But we were inspired by the fact those people cared about what we did.”

Space Case recorded three albums in five years and were the first group to represent New Zealand at the Singapore Jazz Festival.

“A bunch of hedonists, they called us,” said McNabb. “They don’t drink and we had [the late bassist] Andy Brown.”

McNabb’s creative career outside of commercials and soundtracks was bedevilled by the vagaries of the record industry and the fluctuating popularity of jazz – “it’s absolutely got to do with how many times you see the word ‘jazz’ written in the newspaper, it’s about the perception out there. If they never heard the word, it’s not there” – and by not being a good businessman.

But he just kept going and released solo albums under his own name, including a fine trio recording, Waiting for You, in 1987 (with Gibson and Brown); recorded in New York with acclaimed bassist Ron McClure (formerly of innovative groups led by saxophonist Charles Lloyd and pianist Mike Nock, then Blood Sweat and Tears) and drummer Adam Nussbaum (Gil Evans Orchestra); recorded with his groups Modern Times and Band R; and more recently was an integral part of the innovative Salon Kingsadore with guitarist Gianmarco Liguori.

“I am of the peculiar belief that you don’t do anything, it all just happens to you. I never planned any of this. I just went along for the ride.”

McNabb’s name appears on dozens of albums and each is distinctive and different, as he has always sought out musical challenges.

Writing the soundtrack for Greenstone allowed him to compose for an orchestra and traditional Maori instruments (played by the late Hirini Melbourne); doing big television pop extravaganzas meant he had the chance to write for three choirs; and commercials were not just bread and butter but a creative challenge.

“I’ve always been a bloodsucker for any music from anywhere that would expand my music. I’ll listen to music from Macedonia – not a lot – but just to get the idea of what they are about. I’ll occasionally look at YouTube, too, but I can’t handle the sound or videos of bands. They must be boring to watch,” he laughed, before observing that jazz groups and him bent over a keyboard were pretty boring, too.

Mindful of the preconceptions the word “jazz” carries, he said, “What I’m doing now I call ‘not-jazz’”.

He always experimented, even as a kid scraping around inside the family piano to get other sounds out of it.

He noted that the opening track on his 2000 Band R album The End is the Beginning starts with dialogue from space flights, before including crowd noise from New Zealand vs Pakistan at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, which he taped off television and looped, adding in a recording of a person singing at a Korean funeral, which he edited and split. “Then the electric piano comes in. I like to do stuff like that.”

That for him was the joy of the studio (“I’d spend 24 hours a day there if I could”), but even that couldn’t compete with getting on a bandstand and just playing.

“I like to write stuff you don’t have to rehearse, you just start because, ‘I’ve got the melody so don’t worry about it and here we go’. The less you put down [on paper], the more freedom you have.”

Gibson agrees: “And the more people in the band have to think for themselves; if there’s too much on the paper, my ears can turn off about 80%, and music is about the ears not the eyes.”

“I just want to get started,” said McNabb. “Too much talk. You’ve got to catch the wave. Time to start playing and we’d be away. What do you need to know? ‘It’s in G.’

“You know, I started to learn jazz as a boy and somewhere along the way someone said I had to learn the standards, so I thought, ‘Okay, I better learn standards’, but gradually the free thing starts to disappear in your playing because you don’t get to be put in a situation where you can do it . . . but here we are full circle with Frank, and Gianmarco in Salon Kingsadore, and playing like that again. Hopefully, it’s completely free and it’s, ‘What is it going to be today?’”

Gibson (speaking before McNabb’s death): “That’s what he’s always had and even at this stage I’m coming here to play with him and he’s drawing things out of me that I never knew I had, so being around this man for me has been huge. Huge.

“He turned me onto the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Paul Bley, anything that was new he knew about and that gave me self-belief to do it. And just recently he told me about [New York jazz group] Mostly Other People Do the Killing.”

And despite what was happening to his body – morphine daily – McNabb was still searching for sounds, still playing, and still out there. The two pieces he and Gibson recorded will appear later this year, he had other material he was preparing for release when he could (“I’ll just send them out with some hand-painted covers to a few people”), and he recently played short sets with Salon Kingsadore and Gibson at small venues.

“I don’t worry about death, I have my own feelings about that. The thing I don’t want is pain. The thing is you can’t think about death because we don’t know what it is. You think, ‘What pain am I going to have on the way?’ and you don’t want that. I have no trouble accepting the morphine, thank you very much.

“I’ll just keep going and they keep adding it and there’ll be a day when I can’t stand up and that’ll be it. But it’s just a process and we’re all going to go through it some way or another. I’ll be all right as long as I keep gigging.”

And because of that, he looked forward to getting on stage with the same enthusiasm he always had: “There’s nothing better than the first tune and I’ve told the bass player ‘We’re in G’ and I just start and you don’t know what’s going to happen. That moment for me is just joy . . . and here we go, off into the infinite.”

post a comment