Graham Reid | | 3 min read

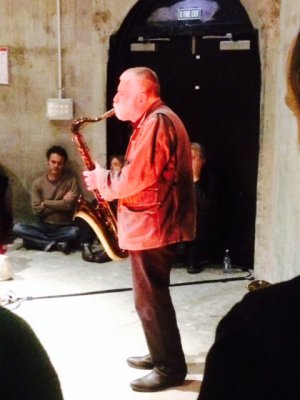

Brotzmann, Uuskyla, Nielsen: Noise Like Wings

German saxophonist Peter Brotzmann – on a short solo tour early next month – recalls the only other time he was here. In the Eighties he and bassist Peter Kowald offered their muscular, free-form jazz improvisation at a time when “there was no audience for this music in New Zealand”.

“I remember playing Christchurch and after the concert – and it was not a big audience – there was nobody left. So we went back to our bed'n'breakfast and killed the last bottle Scotch,” he laughs.

Brotzmann is a pioneer of contemporary European jazz whose singular, often intimidatingly intense, sound came to international attention during the volatile year of 1968 with music which captured those politically charged times.

He's dismissive of the label musicians such as himself were given: “I never liked that 'free jazz' bullshit. It had importance and meaning in the Sixties in Europe when a lot of political things started to move and music was a part of that. But 'free jazz' is an invention of some journalist.”

Brotzmann insists – as someone who plays “jazz music” – he is part of a continuum. He learned from predecessors and peers, and singles out American saxophonist Steve Lacy and trumpeter Don Cherry who showed him style was unimportant, that jazz was the history of personalities and what you could learn from them.

“Great people like Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk just did it the way they wanted to find out who they were. In the end you're never going to answer that question. The goal is somewhere far away but you come closer and closer.”

He still finds value and interest in the music of Sonny Rollins and Coleman Hawkins but jazz selling points or fashions in the past half century – fusion, funk, the neo-conservative movement defined by Wynton Marsalis and the European ethos of the ECM label – are not his way, nor is the attendant fame.

“I'm quite a modest guy, I just want to find out who I am. The main thing is you must like what you do, like to be on stage . . . and play your arse off.”

Born in 1941, Brotzmann was eight when he first met his father who was repatriated from a Russian prisoner-of-war camp. That incident, and his art courses in Wuppertal where he has lived since studying there at 18, shaped his social, political and musical consciousness during the Cold War.

“The after-war Germany had this grey and dusty [chancellor Konrad] Adenauer government with still a lot of old Nazis. But we were young guys who had the chance to travel and see other nations and how they had another way of life. When I first went to Amsterdam I could breathe and felt free. Everything was much more open.”

The motto for his generation was “never again, never again” and that guided his artistic and musical life. Today, he says, people are less interested in politics but personal freedoms in Western democracies are being eroded.

“That's why I'm still on the road. In my way I fight for my own freedom and for other people's too.”

At 73, his demandingly physical style of playing, age (“I feel it in my bones in the morning, but I still have to do this”) and the punishing touring schedule has a price.

He admits he didn't look after himself for decades (“I was drinking a lot until my body told me I wouldn't make it too much longer”) so overnight he quit the booze in 2000. And, as man who depends on his lungs, he was also a heavy smoker.

“Oh yeah, my lungs are fucked,” he laughs. “It's really serious and sometimes it's hard to get enough air in.

“The good thing is, blowing out still works fine.”

There is a review-cum-overview of Peter Brotzmann's solo performance in Auckland at Elsewhere here.

Doug - Apr 28, 2014

Thanks for posting this Graham. I love his music but I would never have found out he was visiting without this. I'll definitely be going to his Wellington gig.

Savepost a comment