Graham Reid | | 1 min read

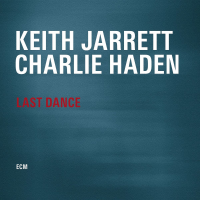

Charlie Haden w Keith Jarrett: Goodbye

What a sad set of coincidences, this duet album with pianist Keith Jarrett was released internationally two days after the great bassist Charlie Haden died. Now look at its title.

And the final piece of the nine is their soft and considered treatment of a Gordon Jenkins tune . . . Goodbye.

Haden was the arguably the most important and innovative (and musically daring) bassist of his generation. He stood alongside the young Ornette Coleman when barely in his 20s for cornerstone albums such as The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century and This is Our Music (all such prescient titles) and later played with Alice Coltrane, Pat Metheny and John McLaughlin.

Few musicians could claim to have worked with such a diverse cast as Haden. In his time other than his long association with Coleman he also played with Yoko Ono, Jan Garbarek, Ringo Starr, Beck, John Scofield, Archie Shepp, Art Pepper, Dizzy Gillespie, Carla Bley, Ginger Baker, Ricki Lee Jones, Pat Metheny . . .

He was genre-blind.

And of course he was in Old and New Dreams (alongside other Coleman alumni) and Quartet West with New Zealand-born pianist/composer/arranger Alan Broadbent

And so many more.

Born in Iowa, he never forgot the country music of his childhood and late in life -- sometimes with his son Josh (of the group Spain) and friends -- returned to that other Great American Songbook of traditional ballads like Shenandoah.

A quick look at Elsewhere's back-stories turns up over 20 references to Charlie Haden (here), among them this essay written many years ago.

Haden was a resolute leftist in his politics but an all-inclusive musician who seemed to find not just the best people to work with (in truth, they found him) but the best in himself to bring to any project.

It seems strange to write about Charlie Haden (who died age 76) in the past tense, especially when listening to this album -- yet another of those quietly considered selections of standards which Jarrett (pictured on the left, with Haden) has been exploring with Haden for a couple of decades now.

It seems strange to write about Charlie Haden (who died age 76) in the past tense, especially when listening to this album -- yet another of those quietly considered selections of standards which Jarrett (pictured on the left, with Haden) has been exploring with Haden for a couple of decades now.

Charlie Haden was never a sentimentalist in his playing, not even when harking back to his childhood.

But given this album, its title and that final track which might leave longtime admirers weeping for what we have lost, we are allowing ourselves to be sentimental about his passing.

post a comment