Graham Reid | | 4 min read

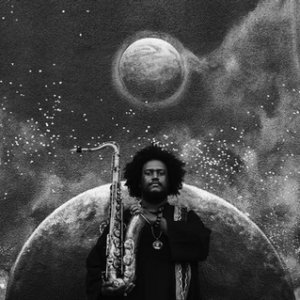

Kamasi Washington: Clare de Lune

If progressive rock of the late Sixties and early Seventies taught us anything it was this.

That only a rare musician (Pete Townshend of the Who, the acerbic Frank Zappa, Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull, Peter Gabriel with Genesis . . . and not Rick Wakeman) had it in them to pull off a lengthy and consistent concept album.

Perhaps it was not in the DNA of a musical form which had found its feet (and some might argue its purest expression) in singles.

But jazz is another matter.

Jazz musicians and composers have frequently found the long form a place for expansive expression in suites, themed programmatic music or simply using the time and space available to explore a single idea in depth and divergency.

Whether it be Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Miles Davis or John Coltrane – or many others so easy to name -- jazz artists can revel in conceptual works.

Such ambitious works have been scarce in recent years but the idea is still alive and out there . . . although few would suspect it might come from South Central LA and be helmed by tenor saxophonist/composer Kamasi Washington. He is perhaps best known to hip-hop listeners who read liner notes, and has appeared on albums by the uber-hip producer and electronica experimentalist Flying Lotus.

This enormous project — almost three

hours long across three discs, with a 32-piece orchestra and 20-piece

choir alongside the core jazz ensemble — is appropriately entitled

The Epic (available in NZ through Border Music).

This enormous project — almost three

hours long across three discs, with a 32-piece orchestra and 20-piece

choir alongside the core jazz ensemble — is appropriately entitled

The Epic (available in NZ through Border Music).

Kamasi Washington is at the peak of his powers at 34, has had playing experience with a roll call of jazz geniuses (Herbie Hancock, Billy Higgins, Wayne Shorter, Stanley Clarke among them) but is also a man of his generation. He's worked with Snoop Dogg, Chaka Khan, Kendrick Lamar and Nas.

He also appeared on last year's After the Disco album by Broken Bells (Danger Mouse with Shins' singer James Mercer).

Washington apparently didn't start on saxophone until he was 13 but five years later in '99 won the John Coltrane Music Competition. Obviously Trane is an influence, but — as many passages on The Epic prove — he is also capable of the most bruising playing in the manner of Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler and the young Pharoah Sanders.

There are lengthy parts on the 12 minute Askim on The Epic where — with a holy choir reaching for the heavens behind him — Washington blows his lungs out in the manner of free jazz masters like Peter Brotzmann . . . before dialing things right down into a gently swinging sequence more akin to a Forties big band.

But that's not all which is here because, despite his hip-hop credentials, this is an expansive exploration of what jazz is all about: a salute to that marvellous and rare swinging, free-range idiom where crafted composition and spontaneous creation can happen within the same breath.

Washington nods back to the best and most focused albums of bands like Weather Report (many of whose records are quite unlistenable these days) and even LA jazz-lite, but also across to funk, orchestrated big bands and soul music.

And given this is an album with a theme — which we'll get to in a moment — the spirit of Alice Coltrane (John's widow and Flying Lotus' aunt) also appears in the piano playing of Cameron Graves. (And Brandon Coleman on organ pops in a bit of Jimmy Smith.).

So what is the theme here?

Ostensibly, if we can take something

from some of the titles and the Zen-like allusions in a promo sheet

-- about an old man on a mountain top observing a dojo below, which

turns out to be a daydream — it is about dreams and spirituality,

age and regeneration, and . . .

Ostensibly, if we can take something

from some of the titles and the Zen-like allusions in a promo sheet

-- about an old man on a mountain top observing a dojo below, which

turns out to be a daydream — it is about dreams and spirituality,

age and regeneration, and . . .

If you find some of that within The Epic you will equally find nothing which fits that at all.

The theme here, for these ears anyway, is jazz itself. The Epic is reminder of its possibilities as a stately and swinging art form in the world of hip-hop, rock and even what passes for jazz these days.

By embracing so much tradition from across a number of the black art movements (but conspicuously not hip-hop), Washington is saying that here's a form with a great history of individual and collective genius which, despite frequently being written off as passé or irrelevant, is not only still here but flourishing.

And still capable of expansive expression.

It's an irony that if this were distilled down to just one disc then it would not garner much attention. Its sheer breath is what affirms it.

There's an Ellington-like elegance to some of the horn passages within The Next Step, high melodrama on the bristling opening section of Miss Understanding (which is sometimes Washington's enjoyable default setting) before it settles into taut Coltrane swing, sometimes with the choir behind.

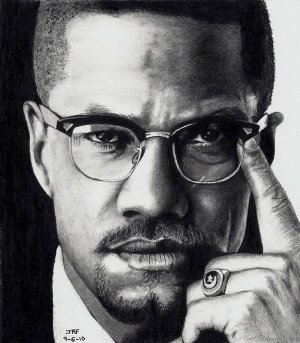

And he's not averse to cutting right

back to the core band for a bright ballad (Leroy And Lanisha where

Ryan Porter on trombone picks up MVP notices again), and soulful

singer Patrice Quinn gets three spotlights, most notably with Dwight

Trible on the penultimate piece, Terence Blanchard's Malcolm's Theme

with the words by the late activist and Ossie Davis distilled from

his eulogy for his friend Malcolm X (pictured, and which includes Malcolm's words sampled).

And he's not averse to cutting right

back to the core band for a bright ballad (Leroy And Lanisha where

Ryan Porter on trombone picks up MVP notices again), and soulful

singer Patrice Quinn gets three spotlights, most notably with Dwight

Trible on the penultimate piece, Terence Blanchard's Malcolm's Theme

with the words by the late activist and Ossie Davis distilled from

his eulogy for his friend Malcolm X (pictured, and which includes Malcolm's words sampled).

And it ain't entirely Washington's show: Quinn gets to enjoy his arrangement of Ray Noble's Cherokee/Indian Love Song from the late Thirties, inna funky mood.

And there's jazz orchestra treatment of Debussy's Clair de Lune also, with an initially disturbing arco solo by bassist Miles Mosley before a measure of elegance resolves it.

So that theme of the old man on the mountain?

If it's there — and that is a big “if” — it's only as a metaphor of a wise one looking back.

The Epic seems to me to be about jazz, the black experience (in politics, life and music) and probably a whole lot more.

Flawed in places of course (how could three hours not have its flat spots or those default settings?) but however you cut it, The Epic lives up to its title.

And it confirms this jazz stuff and these players not only respect the past but can hear a place for it in The Now . . . and The Future.

An epic achievement.

(Doubt it? Check the film below)

Graham Dunster - Sep 29, 2015

Interestingly the running order of the tracks is different on the vinyl and cd issues. Does this affect the creative and/or listening experience? GRAHAM REPLIES: I didn't know that, I just had the CDs. But I doubt it would because as I said, if there is "a concept" it is hard to discern. It's just a monster of a listen any way you cut it.

Savepost a comment