Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Final Thought

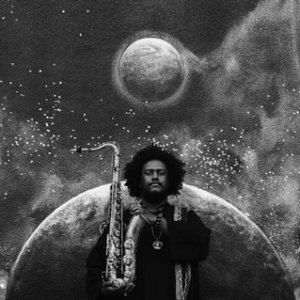

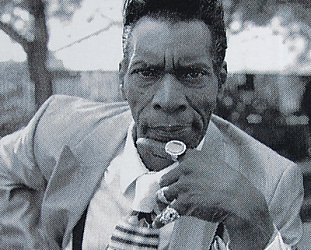

Those music writers who heard it almost invariably put Kamasi Washington's album in their “best of the year” list for 2015, as we did.

And there was a lot of the album – appropriately titled The Epic – to hear.

An all-encompassing jazz concept spread over three discs and 172 minutes, The Epic embraced most aspects of jazz history – big band to free-blowing – and included nods to r'n'b, soul and funk.

Saxophonist/composer Washington – who called in a 32 piece orchestra and 20 voice choir at various points on The Epic alongside his own 10-piece band – emerged almost overnight as one of the most ambitious players of his generation. His previous albums had been on his own small label.

But at 34 he'd already played alongside some of the jazz greats (Wayne Shorter, Kenny Burrell, Billy Higgins, Herbie Hancock) and being part of his generation had grown up on hip-hop in LA, so his name appeared on albums by Snoop Dogg and Kendrick Lamar (he's on the latter's terrific To Pimp a Butterfly of last year).

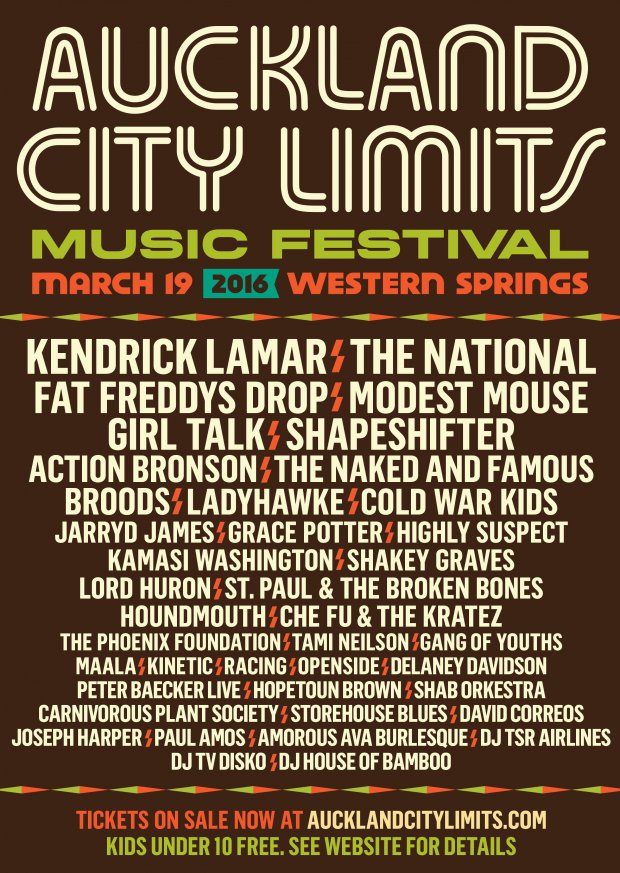

Washington in something to the inaugural Auckland City Limits Festival (as is Lamar, details below) and is bringing his large band with him.

We caught up with his at home . . .

I will be honest Kamasi, the only album of yours I have heard has been The Epic, so I am curious about your musical upbringing. Both your parents were music teachers and I think played, but when you were 13 what was the music you were listening to? Just what all the other kids were listening to?

At 13 I was into jazz actually, earlier than that I was into other music. I think at 13 and 14 that was like my transition and I was really, really keen on jazz. I was also into hip-hop but really got into jazz at that point.

I look at your age and the generation

of music teachers you might have had at university and wonder if they

were influenced by the neo-conservative movement that was prevalent

at that time, or did they have a bigger vision of jazz than that

sometimes narrow view.

I look at your age and the generation

of music teachers you might have had at university and wonder if they

were influenced by the neo-conservative movement that was prevalent

at that time, or did they have a bigger vision of jazz than that

sometimes narrow view.

Some of my teachers were very open-minded and some weren't, but I took the approach of hearing what that person had to offer. I didn't necessarily take on anyone's particular philosophy but I had some teachers that were very forward thinking . . . and some that were less so. It was a mixture.

In LA in general that neo-conservative thing wasn't that strong.

Did you see it as very much a New York thing driven by Wynton Marsalis and his fellow travellers?

It sounded like it was much stronger there than it was here. LA has always been a bit overlooked by the larger jazz community and LA has had it's own little self-contained scene for such a long time.

There were so many musicians playing but the only people that know about them live here.

LA is a big city, not just in the amount of people but the sheer size of it. You can drive for two hours in traffic and still be in LA.

Yes, friends of mine have taken me to jazz clubs in the Valley and they are not places I ever would have found or even known about.

Yeah, exactly.

I understand you also studied ethnomusicology at university: Indian music, gamelan and those kinds of things?

Yeah, music from all over the world, music from North and South America, India, Africa, Asia and Europe. It was really great and eye-opening for me because of all the different possibilities of music and the role that musicians take in societies.

There are places where what people consider music is not like what we might consider music.

Any of that music affect you particularly?

Yeah, a lot of it . . . like the gamelan music and the West African music and East African. And Indian classical music. Some of the traditional Irish music too.

I admire you for that one, I just can't get to that Irish music even though I was born in Scotland. To me a jig is a jig is jig.

(Laughs) Not even the Celtic voice choirs and stuff like that?

I'm aware of it Kamasi but . . . No. When did you first realise you were finding your own voice as a player, how old were you?

It's interesting, that sort of sneaks up on you. When I was younger I was trying to find my own voice but it just sounded like I was wrong (laughs). There were things I was trying to do but probably at 15 or 16, that's when I felt I had something to say in music and could formulate my own opinion, a real opinion.

I've seen the NPR film about The Epic and at the beginning there is that whole sequence of you and the friends you grew up with and play with now. They were friends from teenage years. Are some of those guys in the band you are bring over here?

Oh yeah, I'm bringing all the guys with me: I'm bring Ronald Bruner Jnr on drums, Tony Austin on drums, Miles Mosley on [acoustic] bass, Brandon Coleman on keyboards, Cameron Graves on piano and Ryan Porter on trombone, There's Patrice Quinn on vocals and I believe my dad is going to come out with us and play some saxophone too.

This is a very large touring ensemble,

one of the things you realise I guess is that such ensembles are

expensive to keep on the road.

This is a very large touring ensemble,

one of the things you realise I guess is that such ensembles are

expensive to keep on the road.

Yeah they are. But while I can . . . (Laughs)

Let me turn attention to The Epic. Was it always conceived to be a big, major statement that was going to take its time to say all you wanted . . . even if it was going to be that long.

I thought of it more like . . . I'd been making music for a long time at that point and most of what I had been doing as far as my career was concerned had been making music with other people.

But for this I wanted to really document where I was at now. I didn't know it was going to be three discs (laughs) but I did know the size of the ensemble I wanted. I certainly did know that.

I thought it was going to be . . . I was trying to figure out how I could say it all on one disc and in the end while I was thinking about taking a song or some songs out, then I thought that 17 pieces was the statement and that was the expression of what I was trying to say at that time.

I was having this dream that I had all those songs in it, and that affirmed to me that I didn't need to reduce it and that is what it is, so just be comfortable with it being that.

And that changed my approach. So I stopped trying to make it smaller and let it be what it is.

Without sounding too cynical, if it had only been a single disc it might not have got the attention that it did. The scale of it drew attention.

Yeah, that's the ironic thing. I was afraid to make it big because people might turn away, but it was the reverse of that.

If there was a theme to me it was that here is jazz with a vast history and a relevant idiom today. Was that any part of your intention, or was it just the personal expression saying, “This is what I do”?

Within what I do there is the balance of all that music, I'm a part of the history of this music. All those different stages of the music are part of who I am, so they are all interrelated.

I tried to have my own musical ideas in shaping myself and who I want to be, but I wanted to have that degree of balance to who I was, and not only do this thing or only do that thing.

I've always wanted to have a balance to how I sculpt my music and I've always searched out the parts of music in general that I haven't experienced or don't know.

And that I guess in part explains why we see you recording with hip-hop artists.

Yeah, this is all part of music. Jazz and hip-hop are not isolated islands. Jazz has influenced and been influenced by other styles of music throughout its history. In the beginning it was influenced by blues and gospel and at the same time influencing blues and gospel. Then it was influenced by rock'n'roll, boogaloo, funk in the Seventies . . .

All those things are intertwined.

All those things are intertwined.

So to get the full picture of jazz you have to study all these styles.

Kamasi, I have time for just one more question: If later today you can sit down and take some time for yourself, what album would you put on just for enjoyment?

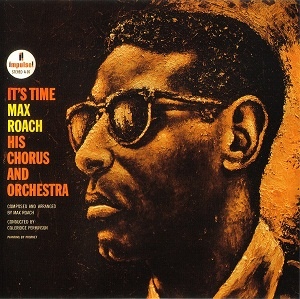

Funnily enough I was just listening to a Max Roach album [from '62] called It's Time.

I'm always searching for something different . . . but right now it's Max Roach.

post a comment