Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Prayer, the Kenny Barron Trio, 2016

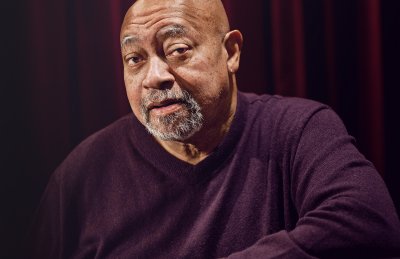

Speaking from his home in rainy New York, 73-year old jazz pianist, composer and educator Kenny Barron sounds like he's possessed of the energy someone half his age. He is genial, quick, witty, looking forward to flying to Chicago the following day to play in an Oscar Peterson tribute . . . and clearly remembers his first paying gig.

It was in his hometown of Philadelphia almost six decades ago.

“Oh sure,” he laughs. “It was actually a band my [saxophonist] brother Bill was playing in. He got me the gig actually. The band was called the Mel Melvin Orchestra, it was at a dance. It was kind of like a variety show.

“You had to play for a singer and a dancer, like a tap dancer or what we might call an exotic dancer, and you had to play for a comedian . . . as well as the audience.

“It was great experience because all the music you used was standards and also a lot of Duke Ellington stuff. “

Barron – who brings his current trio of bassist Kiyoshi Kitagawa and drummer Johnathan Blake to Christchurch for the NZ International Jazz and Blues Festival from May 24-28 – is one of the most outstanding, and diverse, players of his generation.

Of whom it must be said, fewer and fewer are still with us.

The list of people he has played with reads like a lengthy obituary of jazz: James Moody who gave him a gig in New York when he arrived and subsequently recommended him to Dizzy Gillespie with whom he playedd for many years; Yusef Lateef who was a mentor and in whose band he also played; Stan Getz; the great bassist Charlie Haden . . .

Among those he's played or recorded

with who are still around are bassist Dave Holland, trumpeter Wallace

Roney, drummers Jimmy Cobb and Billy Hart, saxophonist Ralph Moore,

violinist Regina Carter, guitarist John Scofield . . .

Among those he's played or recorded

with who are still around are bassist Dave Holland, trumpeter Wallace

Roney, drummers Jimmy Cobb and Billy Hart, saxophonist Ralph Moore,

violinist Regina Carter, guitarist John Scofield . . .

He co-founded the enormously successful group Sphere which was dedicated to keeping the music and spirit of Thelonious Monk alive, has been nominated for Grammy and American Jazz Hall of Fame awards many times, was given an honorary doctorate from Berklee seven years ago, appeared on the Verve and Impulse! labels (among many others), and as a professor at first Rutgers then Juilliard has schooled new generations.

Any way you cut it, Barron has been one of the great sideman but also a band leader in his own right who is at home in many styles from Latin to standards, hard bop to ballads. That ability to move between musical realms stems from his childhood.

Born in Philadelphia, he grew up in a family where music was encouraged.

“My parents didn't play but I came from a family of five siblings, two brothers and three sisters, and my mother insisted that everybody had to study piano. Myself and my brother Bill the oldest – there's 17 years difference between us – both of us became professional players.

“I studied classical piano from the

age of six until I was 16.”

But there was no great jazz

epiphany he says, he loved jazz at the same time.

“I was into jazz very early when I was about eight or nine, primarily because my brother had a fantastic record collection of old 78s, the be-bop stuff like Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray.

“And in Philadelphia we had a great radio station. There were a lot of young players and Philly also had a lot venues for young players, a lot of bars and clubs. They didn't pay a lot of money but they were places where you could play.”

But, inevitably when he was an aspiring jazz teenager, New York – where brother Bill was living and working – beckoned and he went there at 18.

“It was a big move and I don't think my mom was too crazy about me going over there, but the thing that made it easier for her was that my brother was already there. I wound up moving in with a bass player I'd met in Detroit, Bill Wood, who actually lived next door to my brother. He was hardly ever there because he was traveling so much, but I was right next door to my brother.”

In one of those remarkable, but not exactly rare connections, in the crucible of New York's jazz community, in short order Barron joined Dizzy Gillespie's band.

“I got the gig with Dizzy through James Moody who I met when I moved to New York and we were both living in the Lower East Side, the East Village. I could walk to legendary clubs like the Five Spot and the Jazz Gallery.

“Anyway I walked into the Five Spot

one day and Moody was playing and knew my brother so invited me to

sit in, and he hired me. Subsequently a year later he went back with

Dizzy in a small group and I met him on Broadway one day. He

mentioned to me that Lalo Schifrin who was Dizzy's pianist at the

time, was leaving and would I be interested.

“Anyway I walked into the Five Spot

one day and Moody was playing and knew my brother so invited me to

sit in, and he hired me. Subsequently a year later he went back with

Dizzy in a small group and I met him on Broadway one day. He

mentioned to me that Lalo Schifrin who was Dizzy's pianist at the

time, was leaving and would I be interested.

“I said, 'Of course. Yes!'. I'd just got married and wasn't working so of course! So he talked to Dizzy and Dizzy hired me. And he hadn't heard me play, he took me just on Moody's recommendation.”

Barron was with Gillespie for about five years and when back in New York loving the atmosphere of the place.

“In New York in the Sixties there were a lot of clubs and coffee shops, like back in Philly. There were a lot of places where young people could play, you didn't have to be a 'star'. I remember going into the Cafe Bizarre in the Village and hearing [pianist] Cecil Taylor play with a drummer named Clifford Jarvis and it was remarkable and you could find stuff like that.”

But was Barron – schooled on the classics, jazz standards, Ellington and bebop, ever interested in following Taylor, Ornette Coleman and others down the avant-garde/free jazz path?

“It did interest me and that my

brother's thing, the avant-garde. He never recorded too much of that

stuff but a lot of his compositions were leaning to the left. We did

a demo tape that was really out there but it never saw the light of

day,” he laughs.

“It did interest me and that my

brother's thing, the avant-garde. He never recorded too much of that

stuff but a lot of his compositions were leaning to the left. We did

a demo tape that was really out there but it never saw the light of

day,” he laughs.

And despite the changing times – pop and rock replacing jazz in the affections of the new young audience in the Sixties – Barron says it barely affected him. He was still working with Gillespie and after he left the band in '66 he managed to freelance around New York, and then in '67 joined [trumpeter] Freddy Hubbard's band.

“I did entertain getting a day job once, but fortunately I didn't have to that. But in the Seventies I went back school. Yusef was the impetus behind that and encouraged me. At one point everybody in his band – [drummer] Tootie Heath and [bassist] Bob Cunningham – were all in school at Manhattan Community College. We were all in different classes but we all had a composition class with Yusef. It was great experience.”

After Barron graduated he began to run a parallel teaching career an on record he began to include more of his own compositions alongside the standards and other material he had become renown for.

“I always wrote but I think it just started to evolve. I started writing when I was still living in Philly and when Bill was in New York I would send him my compositions and whatever band he was in would play them. He would send letters back saying the guys had enjoyed playing the tunes so that was a lot of encouragement . .. and Yusef played and recorded a lot of my tunes too. And Dizzy before that.

“The biggest incentive to write is

hearing your music played well and as time went on and I began to

take more band-leader roles I would write more compositions,

especially for horns or some other instrumentation. For the trios

though I tended to play more standards.”

“The biggest incentive to write is

hearing your music played well and as time went on and I began to

take more band-leader roles I would write more compositions,

especially for horns or some other instrumentation. For the trios

though I tended to play more standards.”

Surprisingly Barron has done very few solo piano albums – the first At the Piano not until '81 and he thinks there are only maybe five in his catalogue of many dozens of albums.

The band Sphere – keeping alive Thelonious Monk's music – was perhaps the group which took him to the widest audience. It recorded half a dozen albums – mostly of Monk tunes – and toured extensively in the Eighties, right up until saxophonist Charlie Rouse who had been in Monk's band abruptly left in '88. Barron sounds disappointed about that even to this day.

“We were just starting to work and Charlie decided he wanted to move to – he got hooked up with this lady who stole him away so to speak and she spirited him off to Oregon. He started doing a lot of solo stuff and also traveling as a solo artist and using pick up rhythm sections. I don't know why he did that because the band was just starting to get big, we had a tour of California we had to cancel and so on.

“I really believe it was a great band.

“That broke the band up but we reconstituted 15 years later with Gary Bartz and we did one record, and we still have a record in the can.”

Barron himself still records

prolifically – he mentions a new quintet album he has just finished

up – and still enjoys touring.

Barron himself still records

prolifically – he mentions a new quintet album he has just finished

up – and still enjoys touring.

He is looking forward to getting to Chicago the day after our conversation to pay tribute to Oscar Peterson (“He was just a strong player, primarily for me that was what he was about, and he swung like crazy”) and the gig finds him on the bill with other keyboard luminaries including Renee Rosnes playing music which Peterson's widow Kelly found which hadn't been recorded or not that often.

We laugh about how the great Peterson seemed to fall out of favour with critics, but Barron is also generous in his comment: “Sometimes critics unfortunately follow the newest thing which is understandable, and young guys coming out and that might be why that happened with Oscar. They were maybe just paying attention to the shiny things down the way.”

Kenny Barron has rarely fallen from favour, in fact quite the opposite. Over time his reputation has grown and like a fine wine it has its connoisseurs.

Speaking of which . . .

“I can't wait to come to New Zealand, my favourite wine comes from there. It's the Kim Crawford sauvignon blanc I've been drinking lots of that lately,” he laughs.

For more information on the Cavell Leitch New Zealand International Jazz festival in Christchurch go here

post a comment