Graham Reid | | 6 min read

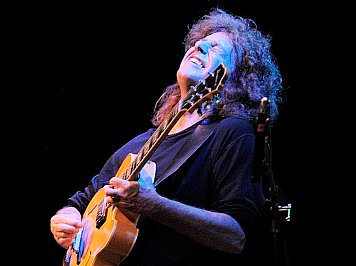

For more than 45 years, over as many albums and 20 Grammy awards, 65-year old Pat Metheny established himself as the pre-eminent guitarist of his generation. That he's not a household name isn't just down to his chosen idiom – he's nominally a jazz musician – but because he hasn't made it easy for an audience.

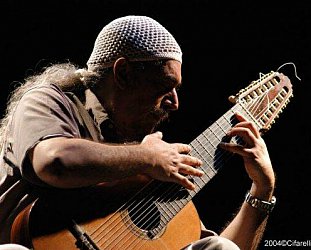

In his catalogue are sublime and commercially successful albums -- notably as the Pat Metheny Group with keyboard player/co-composer Lyle Mays – but also Song X in the mid 80s with saxophonist Ornette Coleman, described by British critic Richard Williams as “practically unlistenable”.

There's the demanding Zero Tolerance for Silence solo outing of guitar noise in 94 acclaimed by Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth as “the most radical recording of this decade . . . searing, soothing twisted shards of action guitar/thought process”.

It followed Metheny's Grammy-winning, orchestrated Secret Story.

There was the hit single This is Not America with David Bowie from the soundtrack to The Falcon and The Snowman, touring with Joni Mitchell, straight-ahead jazz albums and the ambitious As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls which Rolling Stone considered “bridges the gap between contemporary jazz and the new music of composers such as Steve Reich”.

So Pat Metheny – at the Auckland Arts Festival in March with his current group – isn't easily defined, but that's not how he sees it.

“I don't say there was that or this,” he says. “People tend to sectionalise. For me the connection between [Secret Story and Zero Tolerance For Silence] is the idea of filling the entire canvas. From my perspective they co-exist.”

“I never have any expectation in terms of people understanding or not understanding because I've had it happen too many times where my presumption about anything has been wrong.

“So I felt this way from the beginning, the only thing I know for sure is what is meaningful and true to me, and I became a musician because I'm a fan of music. “I would just try to do my best to represent what I love in music, and people do tend to sectionalise it, like it was this and it was that. The more challenging thing is to recognise that it is all the one thing, not that I expect anybody to like all of it or even any of it, I don't have any expectations.

“But I personally do not separate things. To me Secret Stories, the record which immediately preceded Zero – and the connection between those two is one that is rarely discussed – is that idea of filling the entire canvas with paint.

“That's more what it is from my perspective, so the fact they co-exist with each is more the thing, except the actual content of them of course,” he laughs.

“I don't say there was that or this, it's all one thing.”

Although he says melody is a term resistant to definition, from the start of his career he spoke of it frequently, but even here things get slippery.

“It's possible to do something which is overtly melodious, but when I hear a bunch of trashcans knocked down stairs that's melody too. It's in the ear or the be-hearer.

“When I think about my favourite musicians, and they range from Shostakovich and Herbie Hancock to [avant-guitarist] Derek Bailey, there's some glue connecting ideas together. That's what melody is to me.”

If Missouri-born Metheny concedes anything it's that his music is frequently influenced by, and often evokes, the vastness of the Midwest.

His friend and collaborator, the late bassist Charlie Haden spoke approvingly of Metheny's music as “contemporary impressionistic Americana” which the guitarist happily accepts.

“It can't help but be that,” he laughs. “I grew up in a small town and have a map of it, as it existed in 1964, imprinted in my consciousness which I draw from constantly.”

Those formative years in a family of trumpet players also shaped the way he, also playing trumpet until he saw the Beatles on television, thought about the sound of the guitar. Trumpet is about breathing and phrasing, so he thinks and plays in long phrases which shaped the sonic landscapes of Pat Metheny Group albums in the 70s and 80s such as American Garage, Offramp and Travels.

“Oh yeah and it still does. The whole thing of breathing, there's a kind of phrasing that has to be there if you are going to sing or play a wind instrument.

“And very often guitar players, piano players, vibes players, drummers lack a fundamental relationship to breathing.

“But I've noticed a lot of my favourite musicians have some kind of trumpet or saxophone in their background, like Gary Burton and Steve Swallow have that in their background. There's more than a few that I find , I'm not surprised when I find that out that they started on trumpet.

“I not only have that background but I also find myself thinking of the fingerings, it's impossible for me to play a phrase without thinking about that and when I run out of breath I stop.

“I think that's all been a good thing in terms of the kinds of things I consciously assimilated.”

Metheny worked in Kansas City clubs while still in high school, then held a teaching job at the prestigious Berklee School of Music in Boston and played with the acclaimed Gary Burton Quartet.

His first recording was on the 74 album Jaco by bassist Jaco Pastorius, also someone redefining the language of his instrument. Then he signed to the innovative ECM label where his group became among the label's standard bearers until the mid 80s. But he felt constrained by ECM's expectations of how they should sound so moved on.

At 23 he'd said he didn't want to be only thought of as “a hot young guitar player” and now went about proving it, establishing a reputation for doing exactly what he wanted, whether that be solo recordings, with his group or legendary jazz players like Sonny Rollins and Coleman, creating pure noise or beautiful orchestrations.

“That period of time you're talking about, that word [fusion] didn't even exist. It was completely lost on me whatever that was,” he laughs.

“I always saw myself in the context of a whole other thing, that period for me [in my early Twenties] I know you are referencing held zero interest. That playing on one chord and vamps didn't interest me and that was what was happening then.

“So the whole genre aspect of how music is discussed is more like a political description actually, a fashion or a culture discussion. That has always been lost on me for better or worse, I don't even have the awareness to even know what that is.

“So my sense of what I was probably talking about then then had to do more with – I would admit having said all that – and my motive at that time, and I had a very close friend and we were both on a mission from God as it were in our joking, that was Jaco.

“We both felt very dissatisfied about where our instruments were in the spectrum of things around that time.

“I guess Bright Sized Life would be a testament to what we were thinking about, we probably played a lot better than what we did on that record but that was at least a kind of a testament to something of what you are talking about.”

He also embraced the emerging technology of synthesisers.

“I often joke that my first musical act was to plug in. Knobs and wires to me are like mouthpieces and reeds are for others. None of that [technology] has ever been the slightest bit foreign for me, I was always curious about that area.”

He connects that to his grandfather having a player piano and, before picking up an instrument himself, being obsessed with how it worked. When he started his first band he wanted to create a sense of orchestration and technology like the Synclavier allowed that. His recent Orchestrion solo projects further extend his palette.

“When I think about what's possible now it's mind-blowing.”

Metheny has been an enthusiastic collaborator although admits when working on the soundtrack to The Falcon and The Snowman he had little idea who David Bowie was when director John Schlesinger suggested him. Schlesinger thought their instrumental Chris could do with a vocalist. Metheny got some Bowie records, recognised a few hits and realised Bowie would be the perfect singer.

“He came to a screening and was writing like crazy on a yellow legal pad. When the film was done he had a list of about 200 titles, each one better than the next.

“John thought 'this is not America' was it, a line someone in the movie says.”

Bowie took the track back to Switzerland, worked on it then called the band over.

“Man,” Metheny says with audible awe, “it was like being around Sonny Rollins or someone. He was a master. It was one of the greatest experiences I've ever had, to see somebody at the level.

“It's also a song which has more meaning now than at any time in its history.”

So Pat Metheny continues to see a future of limitless possibilities.

“I never could have predicted the trajectory of stuff I've done so I just try to stay open to what's happening.

“There's infinity out there, and I always try to hang with the infinity.”

An Evening with Pat Metheny. Auckland Arts Festival, Great Hall, Auckland Town Hall, Tuesday March 10

There is more with Pat Metheny talking about Ornette Coleman at Elsewhere here.

(This interview was conducted and written a week before the death of Lyle Mays)

post a comment