Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Has it been that long since they had their little shop at the top of Mt Eden Rd?

Their original store might have been small but it was a magnet for the likes of me, mainly because one day – not too long after it opened – I went through their bins near the door to find dozens of very rare free jazz albums by the likes of Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, the Revolutionary Ensemble, Leroy Jenkins, Andrew Cyrille and such other household names . . . and clearly they had no idea what they had.

The prices were so ludicrously cheap I bought as many as I could and returned some time later when I was a bit flush and, being they were free jazz and rather obscure, the remainder were still there.

Then later again I found the two Indo-Jazz Fusion albums by Joe Harriott and John Mayer (not that one!) which I had only ever read about in the footnotes of some jazz books.

These were all thrilling discoveries – I still have them all – but the Harriott albums especially.

I had long been interested in Indian music and that came about by accident. Some time in the early Sixties I ordered some rock album from the World Record Club and they accidentally sent me a Ravi Shankar instead. I am guessing it must have been around the time that George Harrison first clapped eyes on a sitar on the set of Help!

Within a couple of years everyone was banging on about raga-rock and Ravi, and so my discoveries just kept coming, as did the Shankar albums which I snapped up whenever I could.

The raga-rock things was interesting as

Indian microtones and extended jamming, plus drone, entered rock

culture.

The raga-rock things was interesting as

Indian microtones and extended jamming, plus drone, entered rock

culture.

Jazz and folk musicians – notably saxophonists John Coltrane and John Handy, and folk-blues guitarist Davy Graham – had ventured into this crossover territory previously and it's a very rewarding and interesting field. Even classical violinist Yehudi Menuhin recorded a couple of West-meets-East/East-meets-West albums with Shankar.

Over the decades many others have lit out for these fruitful fields and in recent years there seems to be a renaissance in the Indian music crossover. Guitarist Derek Trucks (Allman Brothers, Clapton's band) does interesting work there, and you can hear elements of it in the acoustic music of Robert Plant and Joe Bonamassa.

Indian slide guitar has especially come

to the fore, sometimes through players like Vishwa Mohan Bhatt and

Debashish Bhattacharya. The latter's Calcutta Slide Guitar albums

about a decade ago alerted people to this interesting tradition.

Indian slide guitar has especially come

to the fore, sometimes through players like Vishwa Mohan Bhatt and

Debashish Bhattacharya. The latter's Calcutta Slide Guitar albums

about a decade ago alerted people to this interesting tradition.

But for most Westerners it has been people like the late Bob Brozman (who recorded with Bhattacharya) and Doug Cox (the latter on two Slide to Freedom albums with satvik veena player Salil Bhatt, son of VM) who have popularised the sound.

And Cox's fellow Canadian Harry Manx (interviewed here) who studied under VM Bhatt and plays mohan veena, Indian slide guitar

which has 20 strings, 12 of them sympathetic.

And Cox's fellow Canadian Harry Manx (interviewed here) who studied under VM Bhatt and plays mohan veena, Indian slide guitar

which has 20 strings, 12 of them sympathetic.

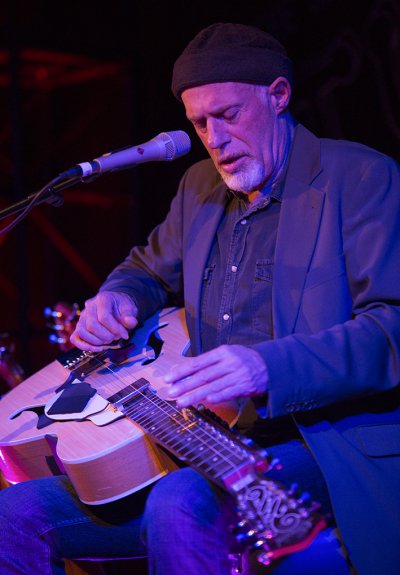

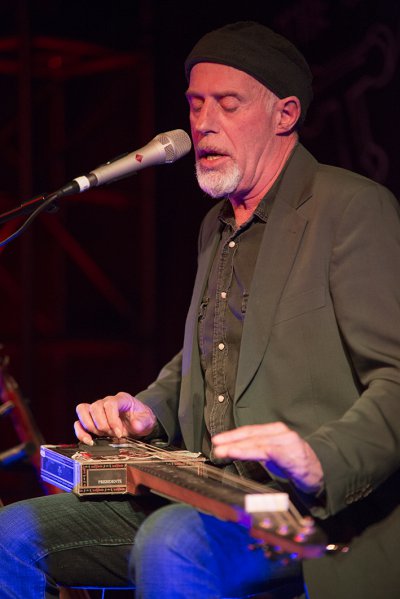

When Manx played this solo show I was reminded again – as if the recent election and my taste in free jazz hadn't proven that conclusively – that you can't judge popular opinion by what you and your friends think.

I assumed just like totally everyone knew about Manx – I've done my best telling people about him over the years – but on the night there were only about 120 there.

Perfectly sized audience for the venue I have to say, but again persuading me I'd be a lousy promoter.

I'd have booked him into a huge room in the expectation of queues around the block.

The droll Manx – who at one point

after some serious blues noted his wife referred to him as Dr

Kevorkian – was clearly delighted by the hushed but appreciative

reception he got, and dryly noted at the end he'd heard New Zealanders

were reserved so thanked us for the seated ovation.

The droll Manx – who at one point

after some serious blues noted his wife referred to him as Dr

Kevorkian – was clearly delighted by the hushed but appreciative

reception he got, and dryly noted at the end he'd heard New Zealanders

were reserved so thanked us for the seated ovation.

It was one of those night, brilliant playing which was grounded in the blues with an Indian twist and punctuated by quiet humour.

Deploying a small artillery of acoustic

guitars – among them that mesmerising mohan veena – Manx

effortlessly shifted from Hendrix's Voodoo Chile (with a nod to BB

King in the middle), Marley's I Don't Want to Wait In Vain, towards

the end rehit the Howlin' Wolf classic Spoonful and dropped in his

best known song I'm On Fire, a cover of the Springsteen ballad given

a Indian flavour on his box guitar . . . but for my money one of the

least interesting pieces of the night. More fruitful were JJ Cale's

Tijuana and the standard Summertime.

Deploying a small artillery of acoustic

guitars – among them that mesmerising mohan veena – Manx

effortlessly shifted from Hendrix's Voodoo Chile (with a nod to BB

King in the middle), Marley's I Don't Want to Wait In Vain, towards

the end rehit the Howlin' Wolf classic Spoonful and dropped in his

best known song I'm On Fire, a cover of the Springsteen ballad given

a Indian flavour on his box guitar . . . but for my money one of the

least interesting pieces of the night. More fruitful were JJ Cale's

Tijuana and the standard Summertime.

The blues hung heavy in the night – Can't be Satisfied was in there too and I swear he changed “feel like snapping pistol in your face” to “pickle in your face” although I doubt it – but found in its low moan mood that junction where Indian drone and slide guitar fit seamlessly together.

Manx made the pairing seem the most

natural and obvious sound in the world.

Manx made the pairing seem the most

natural and obvious sound in the world.

To add a bottom end and beat he had an Apple laptop on the chair beside him but so deftly used it you didn't feel this was some forced marriage of acoustic music and 21st century technology.

Harry Manx is among a small number who have found a fascinating midpoint between American music and Indian microtones, where that slippery slide has a gently keening and exotic sound but remains earthbound by the blues.

That said, Manx is also a rare one and I'm guessing today at least 120 people are feeling they were taken on a wonderful, rewarding and rather different trip.

Took me back a third of a century to the early days of Real Groovy, and before.

Images here by Garry Brandon who has been a concert and commercial photographer for decades in New Zealand. All images copyright Garry Brandon, whose website of archival concert and other work is here. There is more of Garry's work at Elsewhere with these reviews here.

.

post a comment