Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Higa Noboru

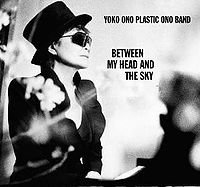

When Yoko Ono released her artistically packaged Onobox in 1992 -- a six CD retrospective of a solo career which had ceased in the mid Eighties -- that would seemed to have been it from the most famous widow in the world.

She was almost 60; had stopped recording because as she wryly noted "there seemed no great call" from the public for any more albums by her; and her attention was elsewhere in managing Lennon's estate and consolidating her avant-garde art status through numerous retrospectives in galleries.

The fascinating Onobox seemed to be her aural epitaph delivered with the resounding thump of a very heavy tombstone, and was talked up in interviews. (Incidentally, Lennon would only get a four CD retrospective.)

However after that and before Between My Head and the Sky released in 2009, half a dozen albums appeared with her fingerprints on them: there were her own Rising ('95) and Blueprint for a Sunrise ('01) albums, and her name was kept in the foreground by the Rising Mixes album (remixes by Tricky, Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth and others), and the '07 tribute album Yes I'm a Witch which included her original vocal tracks with new backings and sonic settings by the likes of The Flaming Lips, Cat Power and Peaches.

(It was her second "tribute", Every Man Has a Woman in '84 were covers of Ono songs by Elvis Costello, Harry Nilsson, Rosanne Cash and Roberta Flack among others).

Another all-star cast remix album Open Your Box appeared the same year, this time by artists such as Basement Jaxx, Felix da Housecat and Danny Tenaglia.

On the most primitive of counts (ignoring the remix, tribute and godawful New York Rock cast albums, and those with Lennon), by 2009 Yoko Ono had released twice as many solo albums as her late husband. Not bad for someone who didn't become a musician until she was in her mid 30s.

And with Between My Head and the Sky, she showed no signs of either slowing down or retreating from making music which is challenging. Some critics were saying this is the best album of her solo career.

That's a big claim and for my money -- for sheer innovation, visceral thrill, commanding presence and undiluted emotion -- she will never top her Plastic Ono Band album of '70, her companion volume to Lennon's equally honest record of the same title.

On that album Ono -- with Lennon playing searing guitar, the like of which he rarely did before or after -- defined her own territory of pure vocalisation which, even today, presents a challange for the unwary.

But this 2009 album -- attributed to the Plastic Ono Band for the first time since her feminist tract Feeling the Space in '73, and therefore inviting comparisons -- had some extraordinary songs, notably the screaming opener Waiting for the D Train.

Here -- once again with her son Sean helming the band, co-producing and putting it out on his own Chimera label -- Ono went her own idiosyncratic way on lyrics which were variously oddball, unintentionally funny for their naivety or emotionally naked, and music which roams from the all-out guitar attack to whispered passages and earnest ballads sung in that childlike, slightly tuneless voice (which I find more irritating than her screaming).

On the ballad Memory of Footsteps it's hard to take lyrics like. "I know my little memory of footsteps will be swallowed by eternal oblivion by the ruthless ocean called the Universe". Or worse, "like the death of a butterfly in a child's heart . . ."

That's fast-forward time into the sonic soundscape of Moving Mountains with its bird calls, Bjork-like vocalisations of quasi-orgasmic moans, taped percussion, distant and echoed trumpet, and washes of water lapping.

With Sean, Cornelius, Yuka Honda of Cibo Matto and others from the New York avant-rock scene of the Nineties, this album is at its musical best on the stuttering electro-rock, slightly Krautrock-influenced material (Watching the Rain) or even the ambient sonic sweeps (Feel the Sand, and the pairing of her reflective farewell I'm Going Away Smiling and Higa Noboru at the end).

But they are rare flashes, and there are far too many mood pieces, spoken word sections and cringe-inducing, trite lyrics of the kind that infected her worst work and politico-poetic tendencies in the Eighties.

When the pace slows (notably the awful Healing where she gets in typically polemic mode and mangled English, "clean the water, each one of us are 90% water") this counts among her lesser moments. And in the Eighties there were more than a few of those as competition.

So, as always Yoko Ono was -- and remains -- a challenge and the light funk or quasi-jazz backdrops here don't serve her as well as brittle and brutal guitar rock, or those swathes of electronica.

Most of this is not even close to that alarmingly spirited original Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band album, or the more recent Rising and Blueprint for a Sunrise, and reviewers who have acclaimed it are being polite if not charitable, and deferential. Much of it is actually bloody awful by her own recent standards, although a remix album (more likely a remix EP) could be okay.

Still, Yoko Ono remained one of a kind and, at 76 when this was released, a whole lot more interesting than Joan Collins who was the same age. At the time of this writing she is 91 and by most accounts is frail but her exhibitions and installations keep her name out there.

And so wasBetween My Head And The Sky the end of Yoko's recording career?

Far from it.

In the decade following this album's release -- now available on vinyl through Chimera -- she released the much better Take Me to the Land of Hell in 2013 and in 2018 she revisited some of her earlier material (and her version of Imagine for which she was now given co-author credit) on the truly dire Warzone.

We'll get to the remix albums -- and yes, there was another one in 2016 -- when we have the time and inclination.

.

Elsewhere occasionally revisits albums -- classics sometimes, but more often oddities or overlooked albums by major artists -- and you can find a number of them starting here

post a comment