Graham Reid | | 2 min read

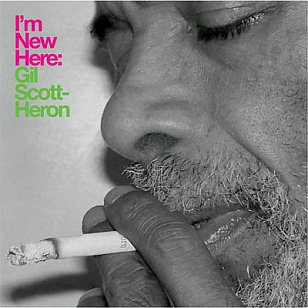

Gil Scott-Heron: Where Did the Night Go

When Gil Scott-Heron -- the American poet, activist and conscience of his nation from the Vietnam years to the Reagan era -- was jailed for cocaine in 2001, then again in ‘06 and ‘07, it seemed it was going to be the beginning of a slow, sad end for one of the most important voices out of black America.

If he had done nothing more than The Revolution Will Not Be Televised -- a wake-up warning to complacent young and middle-class blacks in the time of Black Power activism -- he would still be in the history books.

But for decades -- whether it be Winter in America in ‘74 which captured the sombre mood of a Nixonland nation reeling from Watergate, unemployment and the oil crisis; or Message to the Messengers in ‘93 in which he chastised the shallowness of most rappers -- Scott-Heron was a commanding voice.

Bringing spoken word from the street together with jazz-like phrasing and instrumentation, Scott-Heron connected to a long lineage of black poets and musicians, and pulled that together with a keen ear for dialogue and militant politics.

As with Amiri Baraka (aka Le Roi Jones) and The Last Poets, Scott-Heron was a powerful, insightful poet whose work anticipated rap by a couple of decades.

His best work is compelling even today when the political contexts have changed. (We Almost Lost Detroit about nuclear meltdown.)

But earlier this decade it looked like all we would hear soon would be the obituaries. He hadn’t done much in the Nineties -- and then he was busted, repeatedly.

And now this new album where one autobiographical track is entitled New York is Killing Me and he speaks of the need to go back to Jackson, Tennessee where he grew up and just slow down.

There is a rare honesty and typical self-awareness here: Over dark electronica strings he speaks of coming from a broken home and the love he felt for those who cared for him (the album ends on a reprise of this), he weaves in a knowing cover of Robert Johnson’s Me and the Devil much as Hendrix-meets-Little Axe might have done it; and on the title track (written by Bill Callahan but sounding like an original) over acoustic guitar he says “no matter how far you’ve gone you can always turn around. Turn around, you may come full circle”.

He speaks from within the world of the alcohol-lost and the dead-eye street junkie (Where Did the Night Go, Crutch) and while there is a cathartic quality throughout, some pieces peter out and feel incomplete.

Set against Richard Russell’s electronic soundbeds who has pulled together an album from poetry and some insightful conversations and observation, Scott-Heron is a man who has hard won truths to deliver.

And if his voice doesn’t have quite the commanding power of his most important work, the battered wisdom he brings still sounds like important observations from the battleground of urban America‘s ghettos and underclass.

And it comes from a man who has seen it all, and then some.

Karen Hunter - Feb 19, 2010

Just bought this album on an 'impulse buy' from Rhythm records - was looking for some Spoken Word inspiration - it's totally hit the spot in my soul - it's beautiful, and deep, and reflective, and real. Was just trolling about for more info when I saw this review. I'm giving in 5 stars for beauty, heart, soul and real blues.

Savepost a comment