Graham Reid | | 7 min read

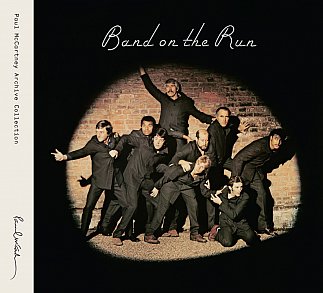

Paul McCartney and Wings: Picasso's Last Words

It's sad in a way, but great albums

often are a result of bad situations: death, divorce, betrayal,

litigation and debilitating substance abuse seem to make for better and more interesting music than cheery times with the family on holiday.

Think about it: Neil Young's Tonight's

the Night (death, drugs); John Martyn's Grace and Danger (divorce,

drink); Marvin Gaye's Here My Dear and In Our Lifetime (divorces,

drugs); John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band (all of the above and more) .

. .

Paul McCartney – whose life has been

alarmingly blessed, aside from the Heather debacle – doesn't seem

like a man who has suffered for his art, but his breakthrough album

Band on the Run of '73 was a battle against the odds. Maybe that was

the kick along he needed, rather than domestic bliss with Linda.

Its predecessors were his McCartney

solo debut of 1970 in which he announced his departure from the

Beatles forever and was largely a lowkey clearing house for mostly

half-finished ideas lying around. Then came the infinitely more

interesting and credible Ram (an Essential Elsewhere album which even

now still stands up), the less interesting Wild Life (with his new

band Wings) and the patchy Red Rose Speedway which felt like a

stop-gap at the time but on reflection pointed a direction.

So by mid 73, despite some hit singles

(notably My Love and Live and Let Die), McCartney was looking like a

man conspicuously failing to keep up the high standard he set himself

in his former band, to which he was always going to be compared,

unfavourably.

Deciding to record his next album in an

EMI studio outside of England he chose Lagos, but before they were

due to leave drummer Denny Seiwell and guitarist Henry McCullough

both quit . . . so McCartney, wife Linda, loyal guitarist Denny Laine

and Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick went to Lagos (where there had

been a cholera outbreak) and discovered the studio was so primitive

it didn't have a vocal booth.

“I mean it's funny out there,” said

McCartney recently, “Africa you know, the politics. It's obviously

not as up to date as London or New York or anywhere in our world

really. They make great music but they're not as technologically

advanced and they weren't then as technologically savvy as we were.

“We expected it to be a proper EMI

studio. But in fact we said, ‘Okay, where are the vocal booths? We

want to go do the vocals.’ And the guy sort of looked at me blank.

He said, ‘Vocal what?’ We said, ‘Yeah. You know, those little

wooden boxes with the glass in 'em and that? Where you go, you put a

mic in.’

“Oh no. They didn't have vocal

booths. So we had to say, ‘Okay, well here's what it is. You take

bits of wood and you make a big box and we gave him the dimensions.

Then you put windows in. You know, you need to seal it up. Stick a

little roof on it, a little door and that's a vocal booth.’

“So they did spend a little bit of

time building them. You know, we'd come in the morning. Tink, tink,

tink, putting the Plexiglas in. But we got it done. I think in a way

the kind of vibe of it all being a little bit homemade found its way

into our attitude.”

Local legend Fela Kuti also accused

McCartney of coming to Nigeria to rip off African musicians, then one

night they were mugged an all McCartney's demo tapes were stolen.

“And, of course, they wouldn't

realize that there was any value in them or they were of any use to

anyone. I'm sure they just either recorded over them or just chucked

'em or sold 'em as blank cassettes.

“So that meant that I then had to

remember the album. And that was okay. 'Cause that was kind of a rule

John and I had always had, 'cause we didn't have cassettes or any

recording devices then. And we always had to remember stuff.

“We used to say, if you can't

remember it, how will the people remember it.”

Yet out of all this – and of course

subsequent sessions back in London – McCartney pulled out the first

great solo album of his career, created a platform for Wings (“only

the band the Beatles could have been” according to Alan Partridge),

and he became a genuine solo artist with a stadium-filling catalogue

that didn't require he dip into his past.

“My big aim after

The Beatles, once we decided to put a band together, was to do

something different, but successful. And that was difficult. 'Cause

all those years I'd been training Beatle style. And I didn't want to

just continue the same thing.

“So I had to kind of avoid anything that sounded too Beatley and make a new style, which was to become the Wings’ style. So by the time we did Band on the Run I felt we'd got it.

"We'd really established something that

wasn't like the Beatles at all. It had echoes maybe inevitably, you

know, because it was me. But it had established its own style.

“Years and years later I was doing an interview with some guy, I think he was from Rolling Stone. We were talking about Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, and he says, ‘My Sgt. Pepper's was Band on the Run.’

"And

for his generation it was as important, so that really made me feel

good, because that's what I've been trying to do, establish something

that was as important as The Beatles were, for someone like him.”

Band on the Run – initially

attributed to Wings, then on reissue Paul McCartney and Wings – has

now been remastered by many of the same team who did the impressive

Beatles remasters released last year, and is the first in a reissue

of all McCartney solo albums remastered as the Paul McCartney Archive

Collection.

Band on the Run now arrives in a

variety of formats originating with the single disc digitally

remastered, essential 9-track standard edition.

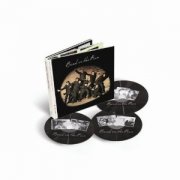

The three-disc (2CD, 1 DVD) special edition features nine bonus audio tracks (including the hit single Helen Wheels), rare footage of the McCartneys in Lagos and behind-the-scenes at the famous album cover shoot, and the original Band on the Run promotional video clips as well as some terrific studio footage and some previously unreleased songs.

It also includes music from the One Hand Clapping television special (highlighted by studio performances filmed at Abbey Road in 1974).

This is all with enhanced packaging and

featuring new liner notes by Paul Gambaccini.

Collectors can go for the four-disc

(3CD, 1 DVD) deluxe edition which adds a 120-page

hard bound book containing many unseen and unpublished photos by

Linda McCartney and Clive Arrowsmith, album and single artwork,

downloadable hi-res audio versions of the remastered album and bonus

audio tracks, a full history of the album complete with a new

McCartney and expanded track by track information for all four discs.

The deluxe edition

also includes a special Band on the Run

audio documentary (originally produced for the 25th Anniversary

edition) and both standard and deluxe versions will be available

digitally.

The original

remastered album and bonus audio content will also be issued in a 2

disc 180gm audiophile vinyl edition that comes with an MP3 download

of all 18 tracks.

Whew!

But . . .

repackaging/remastering aside, does the music stand up almost

four decades on?

Certainly: the increasingly urgent,

autobiographical title-track opener sets the tone picked up in Jet –

one of his best rockers – as an impressive double-whammy. Jet is

lightly echoed towards the end in the slightly woozy and beautifully

orchestrated Picasso's Last Words, and the album closes with a Band

reprise which gives it a loosely conceptual feel.

Picasso's Last Words shows McCartney's

casual craftsmanship. It was written after Dustin Hoffman asked him

to pen something using Picasso's last words (allegedly, “drink to

me, drink to my health”).

Let Me Roll It, a standout, is closer

to Lennon's edgy Cold Turkey and the pop-smart Mrs Vanderbilt (also

echoed in Picasso) was, improbably, voted the most popular McCartney

song by Ukrainians in 2008. Mamunia is a typical McCartney

make-weight however, but the breezy Bluebird adds breathing space.

It isn't a concept album although feels

like one – and the “concept” was so good McCartney tried to

replicate it – with diminished musical returns – on Venus and

Mars two years later, which sold anyway because he was on a high with

Wings and touring heavily.

Band on the Run sold seven million on

release and Jon Landau in Rolling Stone said it was “the

finest record yet released by any of the four musicians who were once

called The Beatles.”

Maybe if McCartney had endured a rougher ride in the following decades we might have had more albums like Band on the Run, a triumph against the odds.

For an overview of Paul McCartney's albums in the Seventies go here.

For an overview of McCartney and Wings go here.

There are numerous other articles on McCartney here.

And here is a film of McCartney talking about the Band on the Run remaster/reissue.

post a comment