Graham Reid | | 2 min read

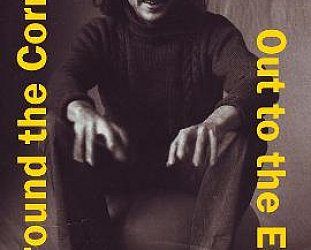

Bob Dylan: Scarlet Town

While music magazines and rock bloggers are exercising their opinion about the Rolling Stones announcing a new tour after five years – just four dates so far – to celebrate 50 years since their formation (most writers asking “Why?” or commenting on their irrelevance), Bob Dylan just keeps traveling on his own road, indifferent to opinion, time and the world in general.

He has just released his 35th studio album Tempest, half a century after his self-titled debut and last week he's played four shows before having a short breather and going on to another 18 in October, 14 in November . . .

For Dylan, now 71, this road goes on forever and the albums just keep coming.

Tempest, three years since his last proper album aside from that Christmas thing (the Stones' last, A Bigger Bang, was seven years ago incidentally) has also got music magazines and bloggers atwitter, but Dylan – unlike the Stones – is being taken seriously.

His last decade has been one of his most fruitful and while the jury will always be divided on his live performances, his albums Modern Times (2006) and Together Through Life (2009) both topped the US. He might be an acquired taste with his sandpaper-gargling vocals, but a lot of people still like it.

Where those albums had a fair dollop of seriousness, Tempest opens with one of his most jaunty songs in many years. Duquesne Whistle – the first single and co-written with Robert Hunter who delivered many of the Grateful Dead's lyrics – is a driving country-rocker of the kind which could be traced back to I Want You, Peggy Day and other more whimsical pieces in his vast catalogue. And it's about a train, a recurring symbol and image in his vast canon.

But after that Tempest gets deep, dark and unsettling. In the vengeful blues Narrow Way he says “your father left you, your mother too, even death has washed its hands of you”; the bone-crack Scarlet Town “where I was born” is a doomed Deadwood by way of darkest Bergman where evil walks; and the relentlessly plodding Tin Angel is a terrifying, nine minute vision.

While this hour-long album – the 14 minute post-modern multiple-perspective title track about the Titanic the weakest – mines a more narrow vein of American music than its predecessors, the riffing blues-rock, country and old school rhythm'n'blues (Early Roman Kings is pure Muddy Waters) are immediately engaging in their familiarity as those allusive, elliptical lyrics conjure up disconcerting doings on empty highways, loss (the slow Roll on John an unsparingly detailed and metaphorical account of Lennon's life and murder), uneasy visions, and broken hearts and bones.

As always, layers can be peeled away: the lyrics of the tender, pedal steel-coloured love song Soon After Midnight suggest a desperate need; women betray, there are are harlots in scarlet, he'll drag that man's corpse through the mud, but the object of his affection will be won. Love comes with an open heart but he's been through hard times to get here.

Throughout however you hear borrowed phrases and even cliches which are thrown in just make a rhyme. They co-exist with iron-hard images and truly original visions ("he threw down his helmet and and his cross-handle sword, he renounced his faith, he denied his Lord . . . ").

As with his previous albums, Dylanologists will delight in deconstructing these songs to find out what Bob has been reading or listening to these past few years. And there's as much brittle humour among the hundreds of words as there are strange visions from the borderlands. Almost. Mostly this is deep dark business where mortality is weighed and the past ever-present.

In Long and Wasted Years – a reflection on a failing marriage speak-sung like Brownsville Girl 26 years ago – he jocularly references “shake it up baby, twist and shout” but also notes “I wear dark glasses to cover my eyes, there are secrets in them I can't disguise”.

Disguises, masks, different personae, revisited and revised myths . . . Welcome to Dylan's disturbing world.

The political/apocalyptic Pay in Blood – I'll pay in blood, but not my own” – is brutal in its damning tone: “I came to bury, not to praise” he says paraphrasing Shakespeare.

Tempest shares its name with Shakespeare's final play, but Dylan has dismissed the association. You'd be wise too also, as well as some of that imagery simply included for the sake of a rhyme.

This road goes on forever . . . and into endless night.

There is plenty more on old and recent Dylan at Elsewhere starting here.

George Henderson - Sep 10, 2012

Robert Hunter!

SaveCheck out his translations of Rilke online

www.hunterarchive.com/files/poetry/sonnetstoorpheus.html

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman - Sep 11, 2012

Hi Graham

SaveThanks! I have not heard it all yet, but your review is a great entree. Listened to Scarlet Town: first time I danced to it to get the physical origins. It's a slow foxtrot, or similar - but the music is somehow Eastern European in its melancholy and sad progressions. Like his Russian Jewish genes are mourning the brutal reality of life there and won't let him forget. I keep seeing soldiers trudging over the steppes.

Keep up the good work. Hibbing, here I come (see my blog)...

www.paparoa.wordpress.com

cheers

Jeffrey

Damien B - Sep 13, 2012

Good work Graham, looking forward to the record

Savepost a comment