Graham Reid | | 3 min read

It was bluesman Clarence 'Gatemouth' Brown who taught me a valuable lesson very early on: it was possible to like a man's music and not like the man who made it. Billy Joel confirmed the opposite: I liked him very much but have never felt an ounce of emotion for his music. But first, let me tell you about a big bag of dope.

When Brown -- a multi-instrumentalist bluesman from Texas -- came to Auckland I got a panic call from the promoter. Clarence doesn't drink, he said, and then let the air go empty between us. I couldn't quite see the problem, and certainly didn't quite understand how I fitted into the picture. All I knew was I had to interview Clarence later that afternoon.

No, Clarence doesn't drink, said my friend dropping such a heavy emphasis on 'drink' that I twigged. Ah-ha, but he does smoke, right? I could almost hear my friend nodding enthusiastically down the line. And now this had somehow become my problem.

To be honest, back then it wasn't that much of a problem, so at the appointed time I turned up at the low-rent motel out by the airport and offered a bag of Northland's finest to my friend.

'No, it would be better coming from you,' he said and shoved it back at me as if it was paper bag of cat droppings. I shrugged and said, fine. But I could see already this interview wasn't going to be quite as straightforward as most.

We knocked on the door of his room and entered. The place was a sauna. Clarence had every heater in the place turned up high and the drapes drawn. By the time I reached the other side of the room I was drenched in sweat and near fainting. But we shook hands and I said I'd been told he might appreciate this, then handed him the bag. He took with a barely audible grunt of gratitude -- ungracious given he knew I wasn't a dealer but someone there to interview him -- and then settled back down in his chair.

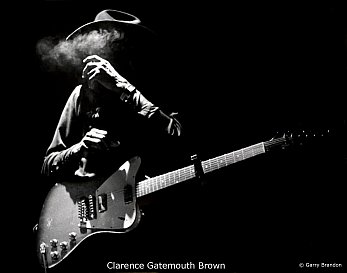

Brown was a lean and rangy fellow, all legs and black cowboy shirt. He wore a black Stetson with a shiny metal band around it and looked like he was born to be sitting on a porch in a rocking chair casting a wary eye at the world. I took him for a gunslingin' sheriff, and it turned out I wasn't far wrong.

He didn't seem to mind that I sat down, but mostly he was preoccupied with filing his hooked pipe with my dope. He puffed away to some satisfaction and what might be considered an interview began.

The walls started to sweat and the place filled with smoke, but never once did Mr Brown suggest I might like to participate in smoking what was my dope. Instead he banged on about the blues and this and that, and I can barely remember much of what was said. I do recall however that he told me no one could touch him because he was -- I knew it! -- an authorised sheriff and to prove it he showed me the badge in his wallet. It had got him out of a lot of trouble he said with a salacious wink.

I should have been more impressed than I was, but I was just woozy from the heat. I read him as an arrogant cuss and the following night at the Gluepot he was even worse.

The music was terrific -- he alternated between stinging blues guitar, jazzy sax and searing countrified violin -- but then started some diatribe about the evils of alcohol and how you should always keep yourself straight. A right hypocrite.

And I realised it was possible to dislike the man but still love his music.

Billy Joel was the opposite.

It always surprises people when I am asked who one of the most interesting people I've interviewed has been and I say 'Billy Joel'. It was just after his break-up with Christie Fashion-Model and it was obviously much on his mind. That, and that for the second time he'd been ripped off for millions by a manager, this time his brother-in-lawyer I think it was.

Anyway I met him in a hotel restaurant in Sydney just as he was about to tuck into a beef and salad sandwich and, obviously without giving it a second thought, invited me to help myself.

And then we chatted. About women and how the separation and tabloid stories were hurting his young daughter, about the nasty business called music and how people rip you off, about his music and where he might go with it once he stopped performing live, and much more besides. It was a genuinely interesting conversation with a man who was down-to-earth and had something to say.

I was almost embarrassed to tell him that I never much liked what he did, but he was also fine with that. He laughed and said he knew it wasn't me who had been buying his albums by the millions.

Gotta say though his show that night rocked a whole lot harder than I had expected so when he came to Auckland with Elton John some years later I told my mates not to underestimate him, and I think he was hands-down winner on that night.

So what have we learned from all this? That it is possible to like the man and not his music, and vice versa?

Perhaps.

But maybe also that sometimes it's more enjoyable sharing a sandwich than a joint.

Footnote: Clarence Gatemouth Brown died on September 10, 2005 of heart trouble, exacerbated no doubt by losing his home in Slidell -- where he was a sheriff -- during Hurricane Katrina. He was 81.

The photo is by Gary Brandon.

post a comment