Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Burlington in Vermont was just starting to take on the complexion of winter when I dropped out of the sky into its verdant beauty. Little wafts of snow were blown around the trunks of the trees and I pulled my collar in close as I left the small airport and looked for a cab.

I liked the place immediately and the cab driver was a friendly guy who took me to my modest motel at a leisurely pace and offered a commentary about a town he was obviously proud of. It looked bleak on this day however, despite the warmth of his words.

With a resident population of around 40,000 -- swollen by 15,000 students from nearby colleges -- Burlington was smalltown America of the kind I had only read about at that time. Clapboard wooden houses on stilts; lawns burned dry by snow; kids who all seemed to know, or know of, each other . . .

I was there for only 36 hours but liked it so much I promised myself I'd go back, although in the decade since -- while I have been in quick striking distance -- I never have.

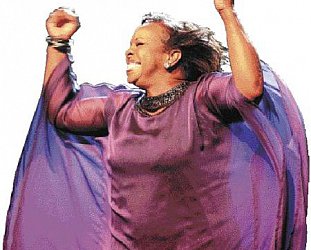

And I never would have gone there in the first place if it hadn't been for Joan Osborne and her naggingly irritating hit single One of Us which bleated, "what if God was one of us, just a slob like one of us?"

It was early 96 and she was all over radio and MTV with the damn thing and my job was to fly to Burlington and do an interview.

Burlington I knew I wouldn't mind because it was just another someplace new -- but Osborne and that hit which announced itself like toothache?

But in the weeks beforehand as I prepared for a month of travel which would take me from Memphis to Tokyo via New York and some places around London and the north of England I read about Osborne and liked what I was hearing: she came off as intelligent in interviews, admired Janis Joplin and could sing like her when she wanted, had started her own Womanly Hips Music label, and she had taken songwriting lessons with the legendary Doc Pomus in New York.

Joan Osborne was my kinda person I decided.

On the night of her show in Burlington's Memorial Auditorium on Main Street (a converted basketball stadium) I arrived early to scope the crowd: a huge percentage of women with their teenage daughters, some men in their 50s with greying hair pulled into pony-tails, and a lot of college students.

It was an interesting cross-section of Middle America here to see the woman I later said had become the Amy Grant of atheists on the back of that one song. (An opinion confirmed by her song St Theresa perhaps.)

The only sour note struck on the night out in the crowd was when a huge security guy offered, unprompted, this opinion to me: "Clinton sucks, I've got 50 guns in my house and that communist wants to take them away from me? There'll be civil war in America soon."

I moved away and went to watch the show.

Osborne was terrific -- but utterly bewildered the kids with braces on their teeth who'd come to see the person who sang That Song About God. Their mums and the college students were kinda lost too.

Osborne came on in darkness and opened a chanting wail which brought to mind a muezzin call to prayer or the qawwali of Pakistani singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. I loved it and was dumbstruck by her courage.

("I did some study of [qawwali] for a couple of week in India," she would tell me in the bus later.)

Later she straddled the microphone stand in a manner which had some mothers almost wilting with an attack of the vapours as she sang Right Hand Man with the killer line, "panties in a wad at the bottom of my purse".

She sang dirty blues that hit a point somewhere between Joplin and Joe Cocker, strapped on a guitar for a stunning reading of Dylan's Man in a Long Black Coat, and kicked in like a go-go dancer for a then-new song about empowerment with the line, "my momma gave me something to make it through this century".

She left you in no doubt just what that "something" was.

It was a thrilling show -- and with a wave of the hand she left the stage as a thousand kids in disappointment (and too young to be familiar with the protocols of rock'n'roll) went as one, "Oh my gaaahd, she didn't do One of Us".

She did of course during the generous encore, but in the bus she offered a weary smile as they prepared to pull out for Syracuse and all points elsewhere on a lengthy tour, "You can't not do it."

"It's weird," she said, "People don't expect so much rock'n'roll if they've only heard the single."

We talked about how in the South the gospel aspect of One of Us had been embraced by a black audience, how she loved soul and as a kid adored Gladys Knight and The Pips (we swapped notes on various obscure album tracks), how she'd gone to New York on a film scholarship and only became a singer when she accepted a beer-fuelled dare and got up and sang some Billie Holiday.

As the driver suggested they get on the road she carried on: how she spent six weeks with the great Doc Pomus; that her current listening list inluded the Fugees, Spearhead, Digable Planets and a swag of other hip-hop artists; and how her job was to make others hear her music because the record company couldn't be relied on to do it . . .

I got the impression she was just glad to be talking about music with someone who cared about such a thing in the new world of marketing and merchandise.

As the rain started to pelt on the windows and we spoke about Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Sufi philosophy I felt a little sorry for Joan Osborne.

She was a 32-year old woman who could sing about panties in the the bottom of a purse, had pro-choice pamphlets in the lobby of her gigs, knew early 60s pop and soul intimately, had hidden a tape-recorder under her sari while studying in India, and had known on a personal level the great Doc Pomus.

But night after night -- for many more years perhaps -- she would have to drive through the darkness to another gig where little girls and their proud Moms would only ever want to hear a song that had taken on a life independent of its author.

It was song which was now crippling to her.

One of the last things she said as the band were finding their drinks and positions for the night-drive was this: "Ultimately my goal is just to keep getting better and eventually I won't have to worry about maintaining an audience."

As I got up to leave her sipping Coke and looking utterly worn out by being her various selves in both concert and an interview, she suddenly got up, hugged my partner of the time (a Sufi as it helpfully happened), and offered me a handshake.

As I noted in what I wrote later about this whole fascinating night in increasingly chilly Burlington, it was very firm handshake.

post a comment